We do not mention his involvement in the crime. Nor do we mention his defence to the matter.

We do not mention his involvement in the crime. Nor do we mention his defence to the matter.

We do not know of his opposition to an error. Nor do we not know of his political stance.

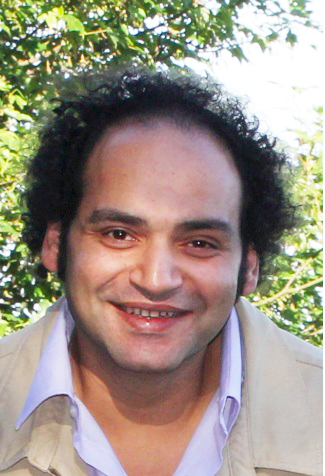

He is Amr Moussa, the veteran diplomat with a long history of nearly 53 years of service in the diplomatic corps, during which he coexisted with every Egyptian government and harmonised with all the Arab regimes. During this service, he never antagonised or opposed any regime.

Amr Moussa, a law graduate, progressed from one diplomatic position to another, starting in 1958 during the reign of the late President Gamal Abdel Nasser, until he become an adviser to the foreign minister during the rule of former President Anwar El Sadat at the end of the 1970s.

Despite the resignation of two foreign ministers, Muhamed Ibrahim Kamel and Ishmael Fahmi, in protest against the number of concessions surrendered to Israel by Sadat, Amr Moussa remained in his position as if the affair did not concern him nor was truly a concern for him. There, he completed Sadat’s work during the rule of dictator Hosni Mubarak and moved back and forth between representing Egypt at the United Nations and serving as his ambassador to India until Iraqi forces overran Kuwait in 1990.

Due to stances which were similar to Mubarak’s policies at that time, he was appointed Egypt’s foreign minister and played a sponsoring role in the peace negotiations that occurred between the Arabs and the Palestinian Authority on one side and the Israeli government on the other, particularly the Oslo Accords, which many writers and analysts consider to be one of the worst agreements ever between the Arabs and Israel.

Moreover, in light of the lack of information necessary to explain the regression that befell Egypt’s stance in support of the International Criminal Court whose founding conference was held in Rome in 1988, during which Egypt shifted from a state clearly supporting the establishment of the court to one against it, this period of time raises a number of questions to which satisfactory answers are still not found.

Ten years after Amr Moussa’s appointment to foreign minister, he was appointed the secretary general of the Arab League. Despite the attempts of government historians to afford Amr Moussa a prominent role during the nearly ten year period of his appointment to this significant position in the most important regional organisation in the Middle East and North Africa, the decline that befell the Arab League during his watch remains the most important descriptor of the league under his leadership.

One manifestation of this decline is the affordance of diplomatic cover to the American forces’ occupation of Iraq in 2003, thanks to the increased dependency of the Arab League on Arab governments, especially those of the Gulf, that are excessive in their authoritarianism and reactionism.

Amr Moussa did not leave the Arab League due to feelings of regret for his biased history towards the Arab governments and Egyptian regime, or in order to join the ranks of the people fighting for social justice and human dignity. Instead he aspired to become president, as if it were an additional advancement with which he could complete his life as a competent employee who never once angered his superiors or sided with their opponents.

As if the fate of Egyptians were to remove a military dictator affiliated throughout his life with corrupt businessmen and then hand over their country to an employee who spent his whole life looking out for himself.

Amr Moussa earned the fifth highest number of votes in the 2012 presidential elections, not because he was the most worthy but rather, in my opinion, because of the frustration and fatigue that settled upon many Egyptians due to the politics of Mubarak’s military heirs. Thus, the ceiling of Egyptians’ ambitions was lowered from a revolutionary president to one just a little bit better than dictators.

In a couple of days, Amr Moussa will turn 76. At such an age, instead of an ambition that has not seen labour, partiality, or stances in of support it, I advise Amr Moussa to retire in order to write his memoirs and present his employment experiences to new generations of diplomats. I recommend that he title his work “How to be Neutral between the Victim and the Executioners”.