(AFP Photo/Gianluigi Guercia)

In the past few weeks, Egypt has witnessed sectarian confrontation in the village of Al-Khosous in Qaliubiya governorate that led to the death of seven deaths. The incident was followed by an attack on St Mark’s Coptic Orthodox Cathedral during the funeral of the Christian victims of Al-Khosous that left behind two dead and 14 wounded.

Egypt’s religious institutions, political parties, civil society organisations and activists condemned this new episode of sectarian violence. And like other sectarian clashes in the past, the incident has provoked debate about how to end sectarian tension once and for all.

My religion is “none of your business”

In an effort to take action against sectarianism, a group of youth and activists initiated an online campaign on Facebook that is calling for the concealing of religious affiliation on national identity cards. “None of your business” (“haga tekhosini” in Arabic) identifies itself as “a campaign against interference in citizens’ private lives by the state, and by other citizens”.

“The religion field in official documents serves no purpose. It is a reminder that the state’s handling of religion over the decades, its classification of citizens on religious lines has succeeded only in alienating them from each other and intensified Egypt’s sectarian problem, and we are seeing the results today,” reads the description of the “none of your business” campaign.

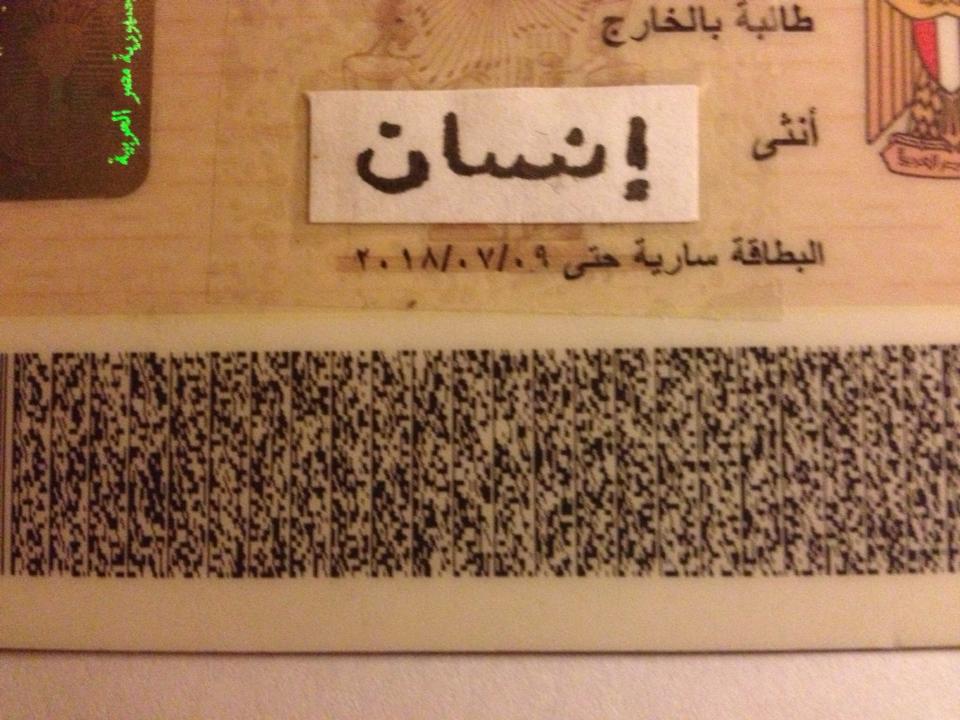

Aalam Wassef, one of the campaign’s organisers, produced a video for the campaign that is going viral over the video sharing website YouTube. As a result of the publicity, the campaign has attracted the attention of about 1,000 supporters in one week. The supporters responded to the campaign’s Facebook page and Twitter account by posting photos of their identity cards with the religious affiliation covered up with messages such as “none of your business”, “guess”, and “human” in Arabic.

response to the “none of your business campaign”

(Photo courtesy of None of your business Facebook page)

Mohamad Adam is one of the organisers of the campaign. He explains how the idea came into being. “We don’t claim by any means that we were the first to initiate such a call. Many before us called for the removal of the religion field from ID cards. However, after Sarah Carr (a British-Egyptian journalist and blogger) reported on the events of Al-Khosous, the cathedral and Maspero in 2011, she concealed religion on her ID. Then it started from there,” the organiser says.

Adam confirms that the recent sectarian clashes are what charged the campaign. “We first posted our own covered ID cards on our personal Facebook accounts. Then when it got popular with friends and colleagues, we decided to create a Facebook page, Twitter account and then finally the video,” says Adam.

He says the page received a barrage of criticism, explaining that any new idea in Egypt takes a little bit of time for people to accept. “We have been living under oppression for so long and people fear change, especially if this new step is related to religion,” he says.

“We couldn’t find any one who gave us reasonable justifications or the purpose of having your religion on your ID card,” he adds.

Previous attempts

As Adam notes, the “none of your business” campaign was not the first to call for the removal of the field of religion. In fact several activists and human rights groups called for it before and after the revolution.

One of them is Almaneyoun, or “Seculars”, movement. It is a movement that calls for secularising the state and society on a grassroots level. It was established in December 2011 and has recently organised a stand in front of the Supreme Constitutional Court in February under the slogan “one nation without discrimination: removing religion from identity cards”. The movement has been accused of propagating atheism and secularism and attempting to strip Egypt of its Islamic identity. However, the movement is continuing its activities and planning for another demonstration on 27 April in Alexandria to continue applying pressure on the state.

(Photo From Almaneyoun Official Facebook page)

Rasha Abdullah is a professor and the former chair of the Journalism and Mass Communication Department at the American University in Cairo. She is among those who called for the removal of religious affiliation. In 2007, she was among a team supervised by Cairo University to conduct a survey on citizenship. One of the questions of the survey asked about cancelling out religion from national identity cards. State Security, which was still active at the time, got involved and removed the question from the survey.

“This really infuriated me because if you’re conducting a survey on citizenship, that’s what you ask about. Ever since then, the question had been on my mind. In 2010, I established an online group on Facebook calling for the removal of religion from IDs,” says Abdullah.

The response to Abdullah’s group helped to attract a couple of hundred members. Nevertheless, when she heard of the “none of your business” campaign, she communicated with the organisers to join the efforts of the two groups and expand its influence.

Abdullah saw the responses against the call and wonders: “Why would we need to have religious labels on our IDs? Is it for people to treat you in a certain way? Is it to favour you if you’re a Muslim?”

She adds: “There are infinitely other documents that people could refer back to if they wanted to know information about the religious affiliation of a person such as the birth certificate. But to carry something on a daily basis that states your religion allows discrimination.”

Abdullah believes that the time of the campaign is significant because “if we spread awareness and asked people why we need religion on our IDs, people will eventually realise that we don’t need it. The main goal here is to spread awareness at this point and get people to think about the issue; about why we need to carry a label saying ‘I’m Muslim or Christian’.”

A tool of discrimination and control

“It allows for establishing a national database for citizens… simplifies procedures…connects all sectors citizens deal with throughout his or her life… It facilitates extracting statistics such as the number of males and females, married, single or divorced individuals and coordinates with security authorities to arrest outlaws who are wanted by authorities.”

This is how the Ministry of Interior’s Civil Status Sector identifies the significance of national identity card and the purposes of different fields. However, no clause interprets or justifies why a field for religious affiliation is displayed.

Gamal Eid is a lawyer and the director of Arabic Network for Human Rights Information. He comments on how a person’s religion is not required information for any governmental papers or institutions.

“The removal of the religious affiliation from the ID has been a demand we pushed for long ago. The only purpose religion might be needed in official papers is when the matter has to do with marriage or inheritance. In these two cases, you can use your birth certificate and not the national ID card,” he explains.

Eid adds: “The religion field on IDs has been used by the state to brown nose Islamist religious groups since the time of Gamal Abdel Nasser and Anwar Al-Sadat. The state is always seeking to prove it is not against religion.”

Adam shares similar sentiments with Eid. He says: “Through national ID cards, the state collects information about its citizens (name, address, religion and marital status and so on). Why would religion be an important piece of info for the state, unless it would be used to discriminate one group against the other?”

Adam explains that the campaign received other suggestions, such as removing the job identification entry of IDs. He posits that those holding powerful jobs may be able to get away with breaking the law because of their perceived influence, whereas citizens of more modest means suffer the full force of a discriminatory police force.

Why keep religion on identity cards?

After the wide response the campaign acquired over one week, debates and discussion took place online.

BBC Arabic’s website held a poll asking readers if they agree to the removal of the religion field from the identity cards. About 1,921 individuals voted in the poll; 57% of them agreed with the removal while 43% disagreed.

However, the response from people on the streets of Cairo disagreed with the online voting. Speaking to seven individuals, their responses were as follows:

Nariman, a 46-year-old housewife, forcefully says: “This is our religion and we shouldn’t disown it in any way. I take pride in my religion; why should they remove it from my ID? Additionally, having it on my ID means nothing to other people. It won’t affect how I deal with others because in daily interactions we [Egyptians] don’t ask each other to show our IDs before talking. Since we were born our IDs had our religion. I think the youth wants this because they’ll manipulate it by pursuing each other while coming from different religious backgrounds.”

(Photo by: Basil El-Dabh)

Fatma, who is 20 years younger, is a tour guide. She thinks it is crucial to have religion on identity cards. “What if some people deceived each other? What if a boy tells a girl he’s Muslim and makes her fall in love with him while he is Christian?” she asks.

Am Mahmoud, a janitor in his 50s, also thinks it is important to keep religion on ID cards. He assumes: “What if someone died all of a sudden and people needed to know about where to bury him in Christians’ tombs or Muslims’? What rituals should they follow? This will help as a quick means of identification then.”

Sherif, 30, a lawyer at a company, argues that legally having the religion on the ID can differentiate between people with similar names. “In some criminal cases, the tiniest differences can help identify the right suspect. Also, I do not think having religion affects relationships between citizens, rather it’s between the state and its citizens. Until Egypt develops a good documentation system for of its citizens, having as much information on the ID as possible is useful from a legal aspect,” he asserts.

One dissenter who disagreed with this crowd was Marian, a 45-year-old housewife. She says: “No, it shouldn’t be there. Religion should be disentangled from politics. Having religion on IDs is related to the current tensions the country suffers from.”

Facing the waves of criticism

Similar responses echo these comments on the “none of your business” campaign. Adam, in response to them, thinks the campaign is not against the Islamic identity of Egypt nor religion in general.

He says: “At the time of Prophet Muhammed, the people did not have ID cards to prove they were Muslims. Also, faith is kept in the heart, we don’t want a label to be used to favour the majority over the minority and same thing goes for the minority. We do not want to use a piece of paper to receive privileges. We want everyone to be equal by the law and the state.”

He cites the example of Lebanon which removed the religion field from national identity cards in 2009. There, identity cards were associated to sectarian violence. Adam explains: “We saw in Lebanon how killings used to happen based on your religion if you’re Sunni or Shi’a Muslim or with any other religious affiliation you could be killed in the street. After removing the religion from ID, the situation got a bit better.”

“We need to learn from countries with no IDs for their citizens like the United Kingdom and neighbouring countries that faced similar sectarian issues like us,” he adds.

The “none of your business” campaign was launched without a long term plan. However, after receiving wide support across social media outlets, the campaign expects to apply more pressure and spread more awareness. According to Adam, the campaign is now planning to approach sheikhs of Al-Azhar, clerics from churches and political parties.

He says: “We are merely proposing an idea that will improve the status of citizenship in our country and make the state neutral towards its citizens. We are not imposing our will on the people, but we will continue to engage in discussions with those who disagree with us until we reach a conclusion.”