When Nicolas Sarkozy cruised to power on May 7, 2007, his foreign policy plans were sweeping. The triumphant president envisioned a grand scheme for the Middle East and North Africa. Under his guidance, France s supposed Arab policy was to be rectified with a more balanced policy.

Sarkozy believed that his break with his predecessor s approach to the Middle East would better advance the cause of peace and prosperity in a region he once admitted he knew little of. Through the creation of a new Mediterranean union, he dreamed that a proud and unapologetic France would vigorously and effectively prod its former North African colonies and Mediterranean neighbors to tackle issues ranging from energy to illegal immigration. The Mediterranean is a key to our influence in the world. It s also a key for Islam that is torn between modernity and fundamentalism, Sarkozy said. In this Mediterranean club, the new French president declared his goal to spread the ethos of civilization through peace, not conquest.

A few months after his assumption of power, however, Sarkozy has come to learn the risks of his contradictory and divisive statements as well as the limits of his international ambitions. Comparing his Mediterranean dream to those of Napoleon III s conquest of Algeria and of Marshal Lyautey, first resident general in colonial Morocco, does nothing to promote mutual trust and understanding between the different cultures. On the contrary, celebrating France s colonial history will only deepen the schism between Paris and its southern neighbors.

To be sure, Sarkozy is a pragmatist. Despite his catering to his far-right electorate base, he understands full well the geopolitical necessities and intricacies of the MENA region. In his trip to Algeria, for example, he was forced to distance himself from statements he made when he was running for president. I did not participate in the Algerian war; my generation does not bear the burden of history, he told his Algerian counterparts. Sarkozy s courting of Muammar al-Qaddafi is another case in point whereby geopolitical motives continue to drive foreign policy. The new man in the Elysee Palace could not turn down ten billion euros worth of deals with the Libyan dictator.

Sarkozy s business pragmatism quickly trumped his calls for steering French foreign policy on diplomacy values . During his election campaign, he vowed not to sacrifice human rights issues and democratic ideals in the pursuit of shortsighted self-interest. Instead of nurturing what he described as the cozy network of personal ties that his predecessor established, Sarkozy promised that his new foreign policy doctrine would not spare authoritarian countries even if they are friends of France .

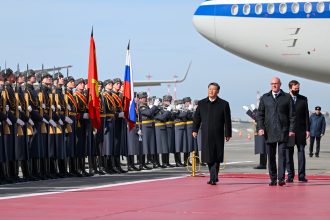

His early denunciations of the principles of cultural relativism and strong condemnations of cronyism and abuse of human rights in former French colonies earned him many accolades. Sarkozy even publicly called on China to respect freedom of speech and freedom of assembly and warned against an aggressive Russia that imposes its return on the world scene by playing its assets with a certain brutality.

But since taking office, the occupant of the Elysee has backtracked on many of his signature issues. His frenetic activity, abrasive leadership style and love of the spotlight certainly distinguish him from his predecessors, but his foreign policy does not depart substantially from traditional French foreign policy. Sarkozy has made no secret of his ambition to play an important political and economic role on the Middle East scene. He has even ventured outside France s sphere of influence by opening a military base in the United Arab Emirates. He tried to solve the Lebanese crisis and mediate between the Israelis and the Syrians.

His failure to do either, however, demonstrates the limits and at times clumsiness of French foreign policy. It is the successful intervention of the Emir of Qatar that defused the Lebanese morass. Sheikh Hamad Ibn Khalifa al-Thani enjoys the trust of the different parties in the Middle East because of his willingness to talk to the Syrians, Iranians, Israelis, Hamas and Hizballah. Likewise, it is also Turkey–not France–that has helped jumpstart the diplomatic stalemate between Israel and Syria.

In the end, the much-anticipated change in foreign policy never came about. With few exceptions, Sarkozy s policies toward the Middle East constitute a continuation of the traditional French international policy of the Fifth Republic. When confronted with the difficult realities of a complex region, Sarkozy quickly learned to temper his ambitions. He now for example supports a watered-down version of his original proposal of creating a Mediterranean union with its own institutions and projects. It is still unclear whether this pared-down version will secure the support of the countries of the region, especially Turkey. Libya and Algeria have already voiced misgivings about the proposal. It also remains to be seen how the never-ending Arab-Israel conflict and the Moroccan-Algerian rivalry for dominance of the Maghreb will affect Sarkozy s initiative.

Anouar Boukhars is assistant professor of political science and director of the Center for Defense and Security Policy at Wilberforce University in Ohio. He is also editor of the Wilberforce University in Ohio. This commentary is published by DAILY NEWS EGYPT in collaboration with bittlerlemons.org.