CAIRO: Amid the noisy, crowded streets and bustling activity in the Cairene squatter settlement of Mansheyat Nasser, in the basement of an unpainted building, 25 women have decided to change their destinies. They came to learn how to read and write.

“One has to be educated in order to know things, so no one can ever take advantage of me, said Nagwa, a 38-year-old mother attending the class.

The class is offered by the Association for Women’s Advancement and Development and is one of many literacy classes for adults that aim to combat illiteracy in Egypt. National campaigns to eradicate illiteracy have been particularly active ever since the foundation of the General Authority for Literacy and Adult Education (GALAE) in 1991.

Get the numbers right

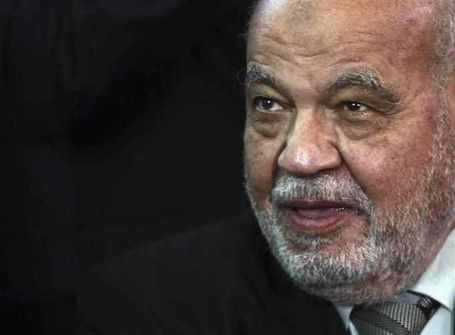

The illiteracy rate in Egypt is currently 27.3 percent, which is around 16.5 million people, said Saeed Abdel Gawad, head of the GALAE, Cairo Branch.

Of the total, males account for 31 percent while females make up 69 percent. In addition, illiteracy is more prevalent in rural areas than in urban areas.

“A quarter of all Egyptians are illiterate, which is a huge number. We have come up with strategies to completely eradicate illiteracy in Egypt, Abdel Gawad said.

In 1996, there were 17.6 million illiterate people in Egypt, a rate of 39.3 percent, said Abdel Gawad, who gets these statistics from the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS.)

“Ten years later, looking at CAPMAS statistics, we found that number only decreased to 17.1 million, and the illiteracy rates went down to 29.3 percent even though the GALAE had educated more than 5 million illiterates. So, where did they go? he asked.

After examining the statistics, Abdel Gawad explained, they discovered that in those 10 years there were 2.3 million dropouts. In the 2006 statistics, they were counted as illiterates because, according to the research center at the American University in Cairo, 30 percent of dropouts who stay away from school for a long period eventually become illiterate.

Another reason for the discrepancy is a group referred to as “can read and write but don’t have a degree. This group amounted to 8.5 million in 1996 and in 2006, they were 7.2 million; therefore, 1.3 million people from this group attended the classes as illiterates even though they are not.

This is why, Abdel Gawad said, “the statistics didn’t change much despite our efforts.

Different strategies

GALAE is heading to less-privileged areas with high illiteracy rate to raise awareness of the importance of education and familiarize residents with the literacy classes offered in the area. In cooperation with the governor of Cairo, there is also a plan to open a literacy class in every mosque and church. With more than 3,000 mosques and 83 churches, there are high hopes for this approach.

Another proposed strategy is to require every university student to educate one person before graduation, and for the nearly 20,000 NGOs in Egypt, those working in the field of education, to each form two or three literacy classes.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has been working in parallel with GALAE and other national campaigns towards eradicating illiteracy.

International partners

“UNESCO is assisting the countries in reaching the goals of Education for All (EFA), which is to cut the illiteracy rate in half by the year 2015, said Ghada Gholam, program specialist in education at UNESCO Egypt.

“Regarding Egypt, we have an initiative in UNESCO called LIFE (Literacy Initiative For Empowerment) which started in 2006 and has given a further push for the government to solve the problem of illiteracy, said Gholam.

For a country to be included in phase one of LIFE, it has to have more than 10 million illiterates or for illiterates to constitute more than 50 percent of its population. Egypt is the first case.

“Within LIFE, UNESCO is working with both GALAE and NGOs to promote the coordinated role of both in the implementation phase, she explained.

Gholam explained that having Egyptian governors involved in eradicating illiteracy greatly supports the cause.

A joint project between UNESCO and the Ministry of Higher Education, which started at two universities, tasked each student with teaching five people how to read and write.

There is another project with UNESCO and GALAE which involves the capacity building and training of facilitators, or teachers. “We develop many training manuals, curricula and fast-track curricula, which have proven to be successful until now, said Gholam.

The heart of the problem

The eradication of illiteracy has been an objective of the government since the 1950s, however, one-fourth of Egyptians are still unable to read or write. While Nagwa and her peers chose to educate themselves, millions of other Egyptians chose to stay illiterate even though there are classes offered in their neighborhood.

“A major obstacle we are facing is that the illiterate person has no desire to be educated, because, as they put, ‘what did the educated people get?’ This is a result of the socioeconomic problems in the country, said Abdel Gawad.

A common example, he said, is a family with five children, one of which goes to school while the others work to help pay for the education expenses. After graduating, the educated one stays at home, unable to find a job that meets his qualifications.

“Therefore, people lose faith in education, said Abdel Gawad.

Both Gholam and Abdel Gawad agree that people need to be made aware of the importance of education. “People should be convinced that education has good return to their level of living, they will improve their social status and that it will be easier for them to find jobs, said Gholam.

Both experts also emphasize the importance bringing together members of the community in the efforts to eradicate illiteracy.

“Every citizen has to be responsible, said Gholam.

“It should start with everyone, it is not the government’s or NGOs’ duty, it is the duty of every citizen in the country, she added.

A UNESCO study identified the needs and the areas of intervention that can promote literacy in Egypt. An important area is the development of flexible programs which suit different learners’ needs and interests, meaning flexible schedules and convenient locations.

Another area is the capacity building of literacy workers by training the facilitators on how to teach adults and providing ongoing development programs for these people to enhance interaction between the learner and the teacher.

UNESCO suggests that more research should be done on how to better understand the problems of the gender gap, the rural-urban context, age and measuring the values and attitude of society towards literacy.

Moreover, existing literacy programs need to be monitored and evaluated in order to know how efficient and effective they are and how they could be improved.