Espionage and intelligence have always had a special appeal on screen where mystery and thrill are placed in a larger-than-life context along with the compulsory notions of nationalism and patriotism.

The genre has proven specifically popular in Egypt, manifested in the millions of teenagers who bought Nabil Farouk’s pulp series “Ragol El-Mostaheel (Man of Impossible) and the millions of viewers who were glued to their TV sets every Ramadan in the early 90s to follow “Raafat El-Hagan, the fictionalized account of real life intelligence agent Refa’t El-Gammal. Before them, the films that charted the resistance against British occupation and the wars with Israel, especially the period between 1967 and 1973, contributed to a wealth of reality-inspired fiction that fueled viewers’ sense of patriotism.

It is easier of course when the enemy is clearly defined. For the first part of last century, it was the Brits. For the second part, it was Israel. Hollywood is no different. From the very start of cinema at the end of the 18th century, Hollywood has persistently succeeded in finding an enemy for America. It started with the native Indians in classic westerns, spread out to include the Germans and Japanese in the World Wars, continued with the Soviets in the Cold War. In the 70s, American film turned its attention inward thanks to the Vietnam War. By the 80s, Hollywood struggled in finding itself a new enemy, toying once again with the Soviets and finally in the mid-90s the Arab terrorists came to the rescue. Intelligently-coined plotlines of thrillers focused mostly on action, ignoring proper characterization of the enemy.

On the local front, where the peace treaty made Israel a friend on paper, the neighboring country was propelled to official enemy status in the abstract form; there is a unanimous sentiment against it but no real confrontation to bank on. The anti-Israel sentiment never vanished from Egyptian films. Dozens of productions in various genres banked on a few scenes infused with this sentiment, impudently flirtingwith viewers’ patriotism in a vain attempt to appear serious. For long though, the once popular espionage thrillers became a scare commodity in Egyptian entertainment.

Enter “Welad El-Am (The Cousins), director Sherif Arafa’s latest marking a grand revival of the genre.

Using contemporary issues and drawing little inspiration from reality, the film reinvents the idea of Israel as the enemy, in an attempt to resuscitate the dying genre. The detachment of stable diplomatic relations from the popular sentiment – where normalization is dismissed, where a cultural boycott is championed, and where tourist exchange remains for the most part limited and in one direction (Israeli tourists to Sinai) – provided fertile soil for the film’s plot.

The film attempts to probe the nature of this undefined relationship; are we in peace or do we still consider each other enemies? In doing so, it’s partially inspired by recent news reports of Egyptian men marrying Israeli women, and the ensuing identity crisis.

This time around, it’s a woman (Mona Zaki) who discovers that her husband and father of her two children (Sherif Mounir) is a Mossad agent. The realization only comes after he drugs her to move her and the family to Tel Aviv; his mission was over and now he wants to settle in his home country with his wife and kids.

Salwa (Zaki) wakes up in Tel Aviv to the shocking discovery that her life was a hoax, a cover; to an overwhelming helplessness as she realizes the power Ezzat/Daniel (Mounir) holds. He can send her back to Cairo, he tells her, but without her children.

In his first film script, Amr Samir Atef – who cut his teeth in sitcom writing – must be given credit for the originality of the story, but that’s also where the praise should stop. The script fell in the trap that many of its predecessors willingly tumble into. The dialogue, mainly the parts that probe Egyptian-Israeli relations and the Arab cause, was too simplistic for even the average viewer. Even the confrontations contradict the film’s founding hypothesis – that relations largely remain vague, neither friendship nor open hostility.

As the Egyptian intelligence officer Mostafa (Karim Abdel-Aziz) arrives in Tel Aviv to rescue Salwa, a slew of unrealistic events and conversations also emerge. En route to Tel Aviv through the West Bank, he, unlike any agent seeking to keep a low profile, gets into a fight with a Palestinian. Egypt’s role in the Palestinian cause – is it a sell-out or a corner stone of liberation efforts? – is slightly and superficially underlined. The issue is of course resolved when Mostafa tells Daniel in another altercation, “We’re coming back, but not now.

The line aims to foster the belief that even though Egypt is in an official peace with Israel, the Palestinian cause will always guide its policies. Egypt will liberate Palestine, but not now. The question of “but why not now? is the only part in the film left to the viewers to figure out on their own.

Questions about the nature of Egyptian-Israeli relations are also raised in Daniel’s attempts to convince Salwa to stay with him and the children in Tel Aviv. The dialogue remains superficial but not as idiotic; he woos her with the notion that Israel is the region’s only democracy, and coaxes her with the prevailing peace.

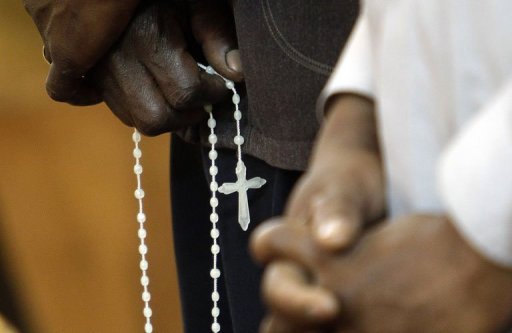

Salwa, an Egyptian with a moderate approach to Islam who has been leading a typical life as a housewife, is left to question her life-long convictions, the ideas she believed in even though they weren’t the driving force of her life. She’s forced to weigh in questions about nationalism (as an Egyptian married to an Israeli) and about religion (as a Muslim married to a Jew).

Zaki again excels here, proving she’s a force to be reckoned with in Egyptian cinema. The scenes that concentrate on her inner conflict prove to be the film’s source of originality. That’s partially due to Arafa’s inventive choice of camera angles and his ability to lead his actors.

He deserves kudos for some of the action sequences as well. If it wasn t for the excessive commercialization of the dialogue that speaks to the lowest common denominator (who are more intelligent than most directors think), Arafa could have pulled it off.

He did an impressive job in selling the South African town he shot the film in as Tel Aviv, where the story is based. And hadn’t it been for the viewers’ certainty that the film was not shot in Israel – due to the prevailing cultural boycott and other diplomatic issues – Arafa might have had a shot.

This is the strongest and loudest message the film sends; a production that investigates our relations with Israel can’t dream of sending its crew there, much less rolling a camera in its streets, for too many political complications both at home and abroad.

The title of the film seems to have left the message open, but everything else screams of this age-old conclusion: The cousins, in reference to Abraham’s two sons Ismail and Ishaq, are destined to remain distant relatives.