Up until not long ago, the films of Yousry Nasrallah were only known to cinephiles and art-house film aficionados. Widely regarded as one of Egypt’s foremost filmmakers, Nasrallah found fame and recognition in Europe, particularly in France, since 1988 when his debut feature “Summer Thefts was released.

2009 is the year that changed everything for him in his Egypt. His sixth feature film, “Ehky ya Scheherazade, was a commercial and critical hit, garnering more than LE 7 million at the Egyptian box-office and scoring coveted slots at the Venice and Toronto Film Festivals in September. At long last, Nasrallah has finally become a household name in his home country, exuding the type of authority that allows him to sell his films without resorting to the current marquee of male stars.

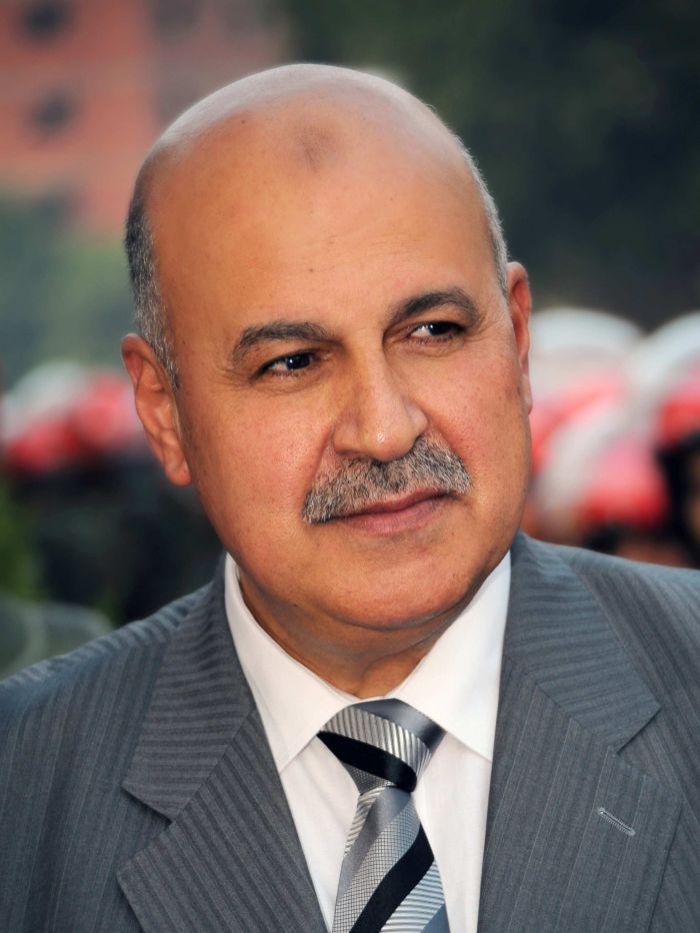

The choice of Nasrallah as our Egyptian filmmaker of the year was easy. For more than two decades, Nasrallah has ventured into a multitude of avenues in the Egyptian society few other filmmakers have dared to approach. Each one of his films is a remarkable piece of cinema, each one is an adventure.

Nasrallah is our Egyptian filmmaker of the year for the singularity of his vision, for his persistence on discounting market concerns and for his tenacity.

I met Nasrallah last week at his apartment for an interview that clocked over two and a half hours. Nasrallah discussed his early beginnings as a film critic, the inhospitable reception his first films were greeted with in Egypt, his influences and the success of “Scheherazade. The following text is an excerpt of the interview which will be published in full over the following weeks.

On his film education

My basic film school was film clubs in Cairo. I used to sneak in film clubs in the late 60s and early 70s using my aunt’s pass because I was underage at that time. And then I became active in the film club movement. I enlisted in the Higher Institute of Cinema for six months before I dropped out. It was awful. That was during that student movement. The guys there were just so reactionary. It was much more fun to be at university than being at film school learning techniques. So, I left and joined the faculty of economics.

I then went to Lebanon and worked for the daily publication Al-Safeer as a film critic just to earn a living and I just fell in love. Rather than staying a couple of months in there, I ended up staying four years. I always wanted to be a filmmaker though. I wasn’t really a critic; I was a bad film critic. I used criticism as a tool to try to find out what I liked about cinema. Then I returned to Egypt to work with Youssef Chahine on “Adieu Bonaparte (1985). This is where I learned film craft.

On being different

Being different from the very start was something that was held against me. But then it also made it much easier for me to impose my vision, all through my career, until now. I was asked recently in Marrakech if young filmmakers should start their careers with ‘easy’ projects that are not different from what’s being shown these days. I told them that if they start by making films that are similar to other movies, they’ll never be able to create something different. On the contrary, you should start radical at the beginning and then afterwards you find common ground to talk with people. Compromise never enters the equation.

On rebelliousness

All my films are informed by an awareness of history, politics and big social issues. But I didn’t want to be [their] function. You need to negotiate your place as an individual so as not to be a mere victim of society and history and politics. We were brought up in the whole neurosis of ‘no voice is louder than the voice of the battle,’ ‘the interest of the group before the interest of the individual’ and all those extreme mottos. As an individual, you were always made to feel that you were not important, that there are many things more important than you so you better put your problems on the side. All my films are informed by rebelliousness against that.

On influences

I’ve learned a lot from [Italian filmmakers] Paolo Pasolini and Roberto Rossellini. I love the black and while films of [Japanese filmmakers] Kurosawa and Mizoguchi. Along with [German filmmaker] Fassbinder, these are the most important directors for me. I’m not talking style at all. These were directors who found themselves on the evil side of what’s good and evil after World War II. Their countries have been totally destroyed. Their art was defined by a will to reconstruct the soul of their broken people after being defeated. In the aftermath of fascism, they were trying to find their humanity. I’m very sensitive to this, for very obvious reasons. But it works there better than it works here.

On Scheherazade

“Scheherazade is a melodrama and I totally assume it. I wanted to dedicate this film to Hassan El-Imam. I realized that if I did that, people would’ve said that I’m being condescending, and I’m not. I really think he’s a great filmmaker in the sense that he knew how to film women. And he was a master of mise-en-scène. His subject matter varied from film to film but there was something really passionate about his films.

For those who accused my film of being sensationalist, well it doesn’t exist in a vacuum. We’re living in a sensationalist world where every day a disaster happens around you.

When the script for “Scheherazade came along, my job was to find a form for it. The characters were well drawn; the script was well constructed. It relied more on storytelling than mood. And because the story was very solid, I was able to work on the mood. It was very liberating. I was free to invent the style for the film and for each story individually without making them look as separate stories. There is a flow; there is continuity in style. Every story has its flavor and progression in form. I had big fun doing it as much as I did in “Gate of the Sun or any of my previous films.