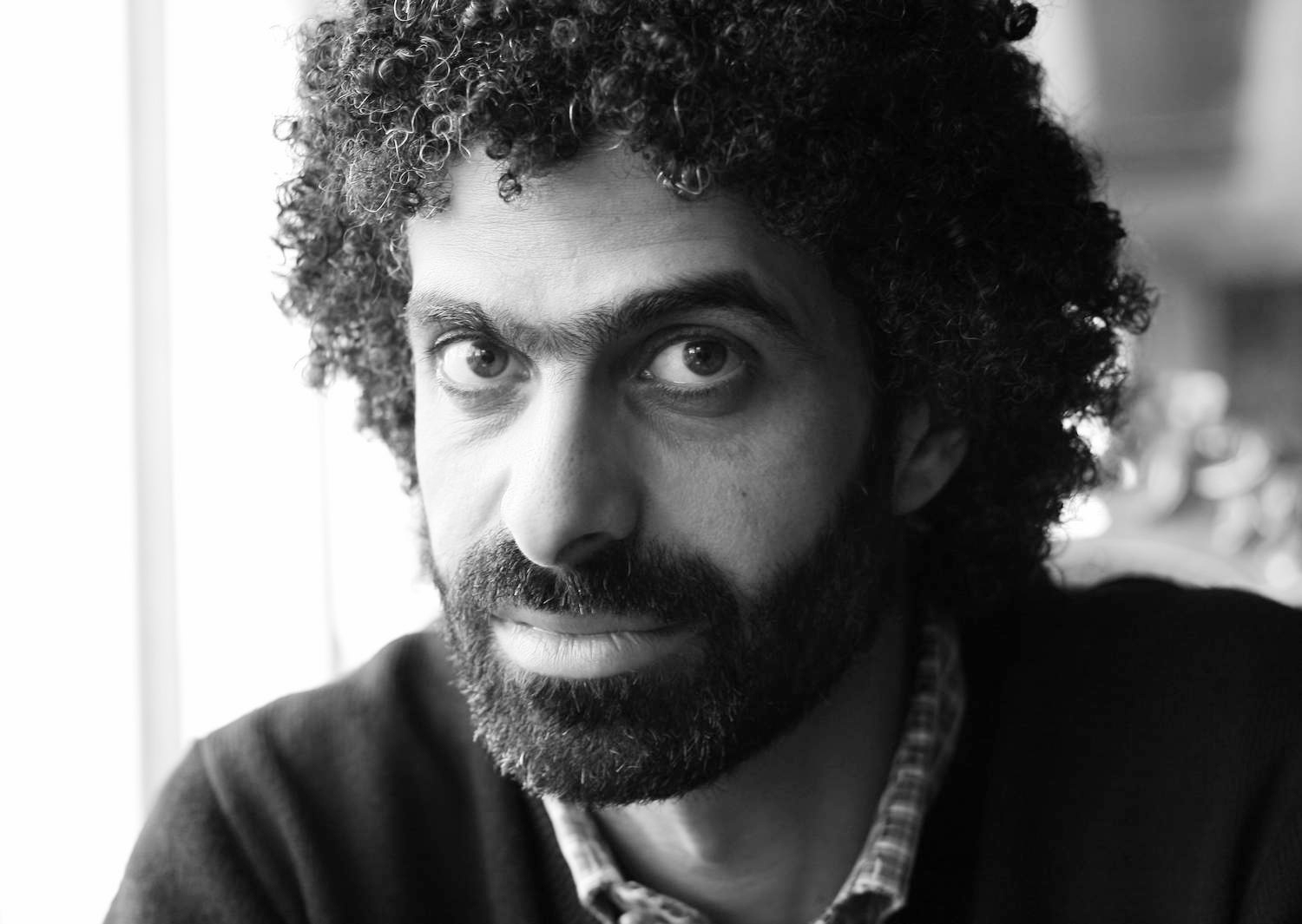

By Nael Shama

CAIRO: Political scientists usually refrain from being drawn into the notoriously slippery forecasting game. Politics is a multi-faceted process, and the various types of interactions among the different players and variables in any historical setting produce a complex situation, that is prone to quick changes and is thus highly unpredictable.

To cite just one example, a grossly optimistic statement on the stability of Iran’s domestic politics made by CIA director in 1979, just months before the fall of the Shah at the hands of Iranian revolutionaries, soon embarrassed the man who topped the world’s largest and richest intelligence agency. The Shah is in control and the stability of his regime is in no danger, he had said. When the forecast of a man with vast resources of information and funds turns out to be so erroneous, others would normally speak about the future very cautiously, if at all.

However, Egyptian politics provides a rare exception to this rule; stagnation reigns because change in many of its aspects is extremely slow, rendering flawless predictions an easy and quick job. That’s why the results of the upcoming parliamentary elections scheduled for Nov. 28 are already known to all close observers, almost in full detail.

There is absolutely no doubt that — as has been the case since its inception in 1978 — the ruling National Democratic Party (NDP) will easily win the majority of the People Assembly’s seats, at least the two-third majority that will pass the legislations it wants over the next five years.

Under current circumstances, in fact, it is fair to expect that no less than 80 percent of seats will be seized by NDP candidates. The abandonment of full judicial oversight of the electoral process (resulting from the 2007 constitutional amendments), the nonattendance of international monitors and the recent crackdown on mass media provide a fertile ground for all sorts of fraud, at which the Egyptian state has already excelled in the past. Moreover, US leverage over domestic Egyptian politics has withered away after previous US-led schemes for promoting political reform in the Middle East had practically receded into irrelevance.

But if vote rigging has been the standard procedure in previous Egyptian elections, this year’s elections will almost certainly be a splendid showcase of what authoritarian regimes can do to monopolize power and undermine rivals. Filling out ballots, transporting thousands of state employees to voting stations (and barring other thousands), using thugs to intimidate rivals, and monopolizing state-run media are the techniques that will be effectively used in favor of the ruling party on election day. Like all masterpieces, the grand show must be preceded by a rehearsal. This practice took place last June with the Consultative Shoura Council (Upper House of Parliament) elections which were riddled with widespread fraud.

So unless a divine miracle drives the NDP apparatchiks to repent their whole lot of past wrongdoings, large-scale fraud would be too visible to conceal this Sunday.

And the discourse accompanying fraud is all set too. When state and NDP officials are confronted with cases tainted with fraud and manipulation, they will confidently contend that these are only “isolated cases.” With deadly earnest facial expressions, they will confirm that the elections have been “fair and transparent” and that they were conducted in a “democratic atmosphere.” In the end, they will not forget to congratulate us on the heyday of Egyptian democracy. That nobody will buy into these delusionary fairy tales isn’t really relevant. It is all about pretending to be democratic anyway.

The Muslim Brotherhood (MB) will be the chief loser of this election. A reiteration of their strong showing in the 2005 parliamentary elections only exists in the wishful thinking of their most zealous followers, not in the givens of reality. The regime is adamant on bringing the MB “back to normal size.” Hundreds of the MB’s members and activists have already been arrested in recent weeks in various governorates, and many candidates affiliated with the group have been disqualified from participating in the elections despite having submitting the required registration papers.

These fraudulent measures will continue to harass the MB before and during the electoral process, and they will have a profound effect on the final results. In 2005, the MB took everybody by surprise by gaining 88 seats (20 percent of the Assembly’s seats). Most likely, Egypt’s most-organized opposition group will not win more than 20 seats this year out of a total of 508 contested seats.

Major opposition parties — Al-Wafd, Al-Tagammu and Al-Nasserist — decided to participate in the elections against the backdrop of widespread political and popular calls for boycott, and opposition from within their own ranks. They may regret that, especially that rumors of deals struck between the regime and these parties have filled the air for months. After elections, internal divisions will continue to tear apart the fabric of these decaying parties, and shifts in leadership are very likely.

With the far-reaching bureaucratic and security arms of the regime openly targeting the MB and tacitly supporting Al-Wafd, the latter will replace the former in becoming the major opposition bloc in the 2010-2015 assembly.

Still, no major success lies around the corner; according to most projections, Al-Wafd’s candidates will win a total of 25-35 seats.

The leftist Al-Tagammu and the Nasserist parties will win a few seats too; most probably, the two parties combined will not get more than 2-3 percent of total seats. After the electoral banquet is wiped out, the NDP throws a few crumbs to these frail parties, to co-opt them into the NDP-led system, and to give to the outside world the impression of a competitive, multi-party political system.

The most ambitious, popular and well-connected of independent candidates will also manage to make it into the assembly. Their percentage in the assembly will depend on the careful calculations made by those in the regime who are orchestrating the event behind the curtain.

To be sure, the regime realizes that too many independents in parliament will cause a nuisance, but their total absence is not too good for the sought-for public image.

Violence predating and accompanying the electoral process is expected to rise this year. Societal violence has risen in magnitude and diversified in technique over the past years, out of a distressing blend of economic difficulties, social frustration and a population boom. In addition, the state is unable — rather disinterested — in curbing the political violence that plagues every election. First, the state is implicated in a great deal of this violence. Second, the mere existence of mob violence benefits the state, as it is used as a useful scapegoat to deflect criticism of manipulation.

When faced with accusations of election rigging, the state retorts by citing cases of violence perpetrated by the followers of individual candidates. It is as if it says: They are the bad guys, not me.

Cairo has turned into a magnet for scores of international journalists who have flocked from everywhere to cover the event. There are good news and bad news for them. The good news is that a fascinating Third World-like mishmash of manipulations, violence and hollow rhetoric is there to witness and report. The bad news is that most Egyptians knew beforehand about it all. Egyptian elections are devoid of suspense drama.

Nael M. Shama, PhD, is a political researcher and writer based in Cairo. He can be reached at: nael_shama[at]yahoo[dot]com.