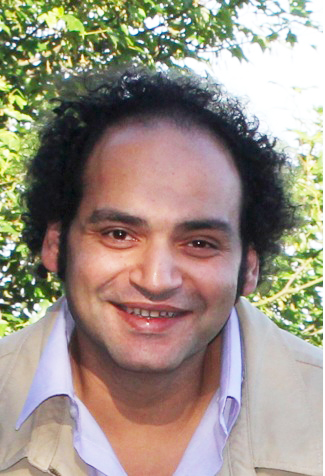

By Ahmed Mohamoud Silyano

HARGEISA: Drought, famine, refugees, piracy, and the violence and terrorism endemic to the shattered city of Mogadishu, a capital ruined by civil war: these are the images that flash through peoples’ minds nowadays when they think of the Horn of Africa. Such perceptions, however, are not only tragically one-sided; they are short-sighted and dangerous.

Behind the stock images of a region trapped in chaos and despair, economies are growing, reform is increasingly embraced, and governance is improving. Moreover, with Yemen’s government imploding across the Red Sea, the Horn of Africa’s strategic significance for maritime oil transport has become a primary global security concern. In short, the Horn of Africa is too important to ignore or to misunderstand.

Of course, no one should gainsay the importance of combating famine, piracy, and terrorist groups like the radical and murderous Al-Shabaab. But, at the same time, we have seen my homeland, Somaliland, witness its third consecutive free, fair, and contested presidential election. And Ethiopia has emerged as one of the world’s fastest-growing economies, with GDP up 10.9 percent year on year in 2010-2011, rivaling China and leading Africa. Indeed, Ethiopia is one of the few countries in the world poised to meet the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals on time and in full in 2015.

In the wider region, too, things are looking up. South Sudan gained its independence this July at the ballot box. And Uganda has discovered large new deposits of oil and gas that will help to lift its economy.

All of these changes reflect the fact that the Horn of Africa’s peoples are no longer willing to be passive victims of fate and their harsh physical environment. On the contrary, they are determined to shape their destinies through modernization, investment, and improved governance.

After decades of stable enmities, the peoples and nations of the Horn of Africa are learning how to cooperate and align their interests. For example, Somaliland and Ethiopia are collaborating on the construction of a gas-export pipeline from Ethiopia’s Ogaden region, promising new jobs and income for people in one of the poorest and least developed parts of the world.

Although there is much that we can and will do to help ourselves, the Horn of Africa can still benefit from international assistance. But the international community needs to do more than provide food and medicine to victims of famine and drought. Necessary as that is, we need pro-growth investments that will help provide jobs for our peoples and products and resources for the world. That means focusing on promoting market economies and stable government, rather than subsidizing failure and failed states.

Unfortunately, at least with respect to Somaliland, this is not the case. For 20 years, ever since we re-established our independence — we had voluntarily joined with Italian Somaliland to form Somalia in 1960 — the international community has closed its eyes to the successful democracy that we have built. Even more perverse, it appears to be demanding that we abandon the peaceful, tolerant society that we have established and submit to the control of whatever government — if there even is one – rules (or misrules) the remainder of Somalia from the rubble of Mogadishu.

Our successful democratic experiment is being ignored in part because of a hoary ruling a half-century ago by the Organization of African Unity, the precursor to today’s African Union. Back then, with the recent demise of the colonial empires stoking fears of tribal rivalries and countless civil wars, the OAU ruled that the frontiers drawn up by the imperial powers should be respected in perpetuity.

That taboo still claims routine support from many African leaders. And yet Eritrea’s secession from Ethiopia did not lead to other breakaway movements in Africa. Likewise, South Sudan’s peaceful, and internationally supported, separation from Sudan has not led to new calls for Africa’s borders to be redrawn.

A 2005 report by Patrick Mazimhaka, a former AU deputy chairman, cast heavy doubt on the application of this rule in Somaliland. As Mazimhaka pointed out, the union in 1960 between Somaliland and Somalia, following the withdrawal of the British and Italian colonial powers, was never formally ratified. But his report has been left in a drawer ever since.

So when should a people be able to declare their independence and gain international recognition? The Palestinians’ decision to take their case to the UN has put this issue on the front burner. International law is of no help here; indeed, the World Court has offered only scant guidance.

The basic principles that I believe should prevail, and which Somaliland meets, are the following:

• Secession should not result from foreign intervention, and the barriers for recognizing secession must be high;

• Independence should be recognized only if a clear majority (well over 50 percent-plus-one of the voters) have freely chosen it, ideally in an unbiased referendum;

• All minorities must be guaranteed decent treatment.

All three of Somaliland’s parties adamantly support independence, confirmed overwhelmingly by a referendum in 2001. So there is no question of one clan or faction imposing independence on the others. Yet, although Somaliland is deepening its democracy each day, our people are paying a high price because of the lack of international recognition.

World Bank and European Union development money, for example, pours into the black hole that is Somalia, simply because it is the recognized government. Somalilanders, who are almost as numerous as the people of Somalia, are short-changed, getting only a fraction of the money invariably wasted by Somalia.

Justice demands that this change. The national interest of most of the world’s powers requires a Somaliland willing and able to provide security along its borders and in the seas off our coasts. Our people are willing. But, to paraphrase Winston Churchill, give us the tools, and the international recognition, so that we can finish the job.

Ahmed M. Mohamoud Silyano is President of Somaliland. This commentary is published by DAILY NEWS EGYTP in collaboration with Project Syndicate (www.project-syndicate.org)