By Naazish YarKhan

CHICAGO, Illinois: Ayad Akhtar’s “American Dervish,” set in pre–9/11 American suburbia, is a bold debut novel, where the author seems to hold the American Muslim community by the collar, and shake it into recognizing its failings — whether they are anti-Semitism, the unwillingness to accept that Muslims come in various shades or the rush to judge the depth or nature of another person’s engagement with God.

With Quranic verses as its linchpins, the novel portrays the multiple ways in which the protagonists’ understanding of their faith informs their choices. In doing so, Akhtar provides a more complex, nuanced picture of Muslim Americans.

The story follows a 10-year-old protagonist, Hayat Shah, who is enamored with his mother’s best friend, Mina, whom he first sees in a photograph. His fascination grows once she arrives with her preschool-age child to live with Hayat’s family in Milwaukee. A devout Muslim, Mina kindles a love for the Quran and its teachings in Hayat. Her presence also brings laughter to a quarrelling household. But when Mina falls in love with a Jewish doctor, Hayat’s jealousy is stoked by anti-Semitic remarks he overhears at school as well as in the Muslim community, and he lashes out with heartrending consequences.

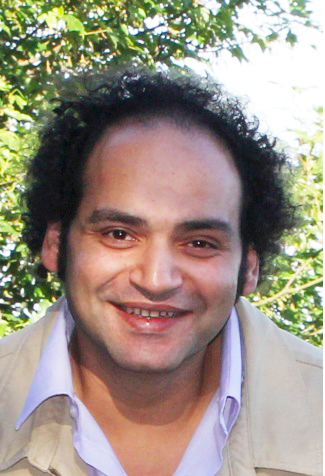

It’s not a coincidence that Akhtar uses a young boy as the protagonist for this story. “I wanted to tell the story of what I experienced as a boy in terms of my fascination with Islam. The learning curve that Hayat is on is experienced by the reader who embarks on this journey alongside Hayat. The novel opens a window to what it feels like to be a Muslim,” says Akhtar.

Colored by Akhtar’s own childhood, “American Dervish” is a tale that does not shy away from complexity or controversy. To make his point, Ayad presents a Jewish-Muslim love story, a marriage between a non-practicing Muslim and a Christian, and he showcases the anti-Semitism that percolates in American society, including in the Muslim community.

One of the many memorable scenes is a vignette in which Nathan Wolfsohn, a Jewish doctor, visits the local mosque. Nathan wants to marry Mina, a devout Muslim who will only marry another Muslim. The day Nathan visits the mosque to accept Islam for love’s sake, the imam launches into an anti-Semitic diatribe in his sermon. Nathan recoils, stung and shocked. “This is not Islam! This is hatred!” he yells.

“What would you have done if I wasn’t there? Would you have stayed through the sermon?” Nathan asks Naveed, Hayat’s father, on their drive home. His question is worth considering by people the world over. How many of us speak up about hate that is peddled in any form, including sermons, rather than only lamenting it privately?

“Why does Islam have to be seen [exclusively] as a positive?” asks Akhtar. “We are flawed…. we are complex, morally compromised characters. It’s difficult for [Muslims] to have an honest conversation about where we are [regarding anti-Semitism], since we are so preoccupied with appearing a certain way, especially after 9/11,” says Akhtar.

To counter-balance his portrayal of the anti-Semitism in the community, in Mina and Hayat’s parents, the author also acknowledges Muslims who recognize familial bonds with the Jewish community. Populated with interfaith relationships, “American Dervish” is in fact an homage to the commonalities between Muslims and Jews — and to Jewish American writers and filmmakers such as Saul Bellow, Woody Allen and Philip Roth who inspired Akhtar, in part because they too are members of a minority religious community in the United States. Non-Muslim readers have found “American Dervish” an accessible way to learn about the Quran, says Akhtar.

In presenting both sides of the coin, Akhtar exposes the chasms and the need to build bridges, as well as acknowledging Muslims and Jews who have already found friendship. There is hope after all, he seems to say. A conversation-starter, this novel does not provide answers as much as it forces readers to dig beneath the surface for their own.

Naazish YarKhan is a Communications Strategist in Chicago, Illinois. Her writing has been published in over 50 traditional and digital media outlets around the world. This article was written for the Common Ground News Service (CGNews), www.commongroundnews.org.