As Egypt plunges further and further into the aftermath of a contentious presidential election, unofficial ballot counts seemed to indicate that the Muslim Brotherhood’s candidate, Mohamed Morsi, had claimed victory with a little less than one million votes. Upon the news, hundreds of Morsi supporters streamed into Tahrir Square to celebrate the victory, but lost in the small celebratory fervor were the last-minute, late-night decrees issued by the Supreme Council of Armed Forces (SCAF) that altered the political playing field in favour of strict military power consolidation.

Al-Shorouk Newspaper

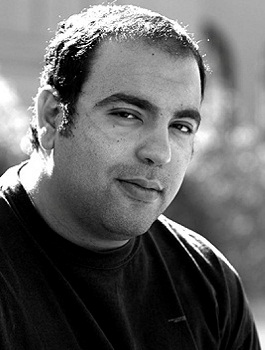

If it’s a map you need to navigate through the past 18-months of elections, violence and judicial decree after decree, Al-Din suggests saving yourself the trouble since the swift pace of political developments are altering the political map dramatically in rapid bursts of time.

Al-Din’s column ‘The change of Egypt’s political Map,’ highlights the Supreme Constitutional Court’s ruling to dissolve the parliament and the Supreme Council of Armed Forces’ (SCAF) sudden announcement of a new constitutional declaration as examples of dramatic political turnarounds that shift power balances politically. Despite early indications of Morsi’s victory, the Al-Din states there are more pressing developments that should accounted for while looking for guideposts during this murky political transition.

The largest of these developments is the SCAF constitutional decree effectively handing all of the political, fiscal and security control to the military. The military took charge over legislative power and process as soon as the Supreme Constitutional Court ruled to disband the parliament, Al-Din wrote. The decree effectively gives SCAF the ability to draft a new constitution, on its own accord, and with its appointed body members.

It was expected that the newly elected president would have authority over the constitutional drafting process writing, however, the military junta has wrestled control of the process and placed it solely in the military’s hands. Egypt is now thrust into previously murky waters of the political vacuum caused by Mubarak’s ouster, writes Al- Din. While it seemed reasonable to allow SCAF to fill the temporary political vacuum on 11 February 2011, the current situation, with a president set to take civilian control, should loosen the military junta’s reigns of control.

It is clear, Al- Din writes, that the political power of the newly elected president of Egypt will be perfunctory and dwarf in comparison with that of the generals of SCAF. Instability and insecurity among the Egyptian public about the transition drove citizens to trust the military and its rule, Al-Din posits. Egyptians, politically exhausted from the revolution and its consequences, believe SCAF will be a source of protection from chaos, Al-Din writes. Now, as the transitional period was set to draw to a close on 30 June 2012, the public finds itself once again under military rule and a unclear map forward.

Al-Masry Al-Youm

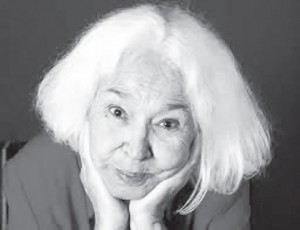

The ‘masses,’ the glorious revolution,’ and the notion of ‘a beloved Egypt,’ are political tools and buzz words used by the ruling elite and its network of profiteers, public officials, and pundits to control the public discourse within Egypt, writers Nawal Al-Saadawi in her column ‘ El-Baradei, Zewail: the Savior and the Dependency.’

Al-Saadawi defends her stance not to participate in any of the transition’s electoral experiments, in order to not provide any material or spiritual leaders. Unconcerned with who will become Egypt’s next president, or the cult-like followings leaders develop in the country, Al-Saadawi writes searching for national saviors to be cheered and adored by ‘crowds’ is an inevitable pitfall.

Critical of Islamists and Salafists, who were enchanted by the power of parliamentary elections, and rushed to gain as many seats as they could in the parliament, and the constitution drafting committee, Al-Saadawi writes that Islamists neglected the centrality of creating a constitution and chose the mad-dash for power to craft the draft. It reeks of groupthink, Al-Saadawi notes, and its groupthink that is destroying critical and creative thinking that is required to unhinge the cultural dependency of citizens from their leaders.

It is cultural dependency, between those who lead and those who are lead, whether in political, economic, social, religious, and moral spheres, that has infused dictatorships and created cults of personalities in democracies. Elections, seen as ‘sacred cows’ of the political process, and similarly applauded across the globe, despite serious shortfalls worldwide, are the foundation of patriarchal democracies, Al-Saadawi.

These massive political failures, Al- Saadawi suggests, led to the outbreak of protests from Wall Street to Tahrir Square. Al-Saadawi, familiar with the rallying cries of crowds and cults of personalities, digs into her rich political history to recall the National Conference of Popular Powers in 1962. Under the rule of Gamal Abdel-Nasser, the revolutions leaders attempted to create a definition of the term ‘peasant,’ in order to win over masses.When it was her turn to speak she suggested ‘farmers are those whose urine is red.’ A doctor by training, Al-Saadawi, knew the all-too real symptoms of the working class farmer who 99 percent of the time suffered from schistosomiasis, a condition that turned one’s urine red.

She was ignored, just as the real problems of ‘peasants’ and ‘farmers’ were ignored. Instead, Al-Saadawi became an enemy in the eyes of the revolutionists, and intelligence officials began investigating her activities. It was that form of critical thinking, Al- Saadawi notes, that this transition lacked. True detachment from popular leaders capitalising on groupthink, is what is needed for the transition to succeed. Revolutionists: We will continue the path

Al-Masry Al-Youm

Tahrir’s revolutionary history is what binds us, writes columnist Ammar Ali Hassan in the column ‘Revolutionists, and we will Continue the Path.’ Hassan shares his memoires of the historical ties between Tahrir Square and the spirit of revolution in the minds and hearts of youth.

He recalls how the square’s corners have housed repeated riots and uprisings over time in 1935, 1946, 1977, ending with the uprising of 2011. Egyptian revolutionaries paid back their tribute to the square, Hassan notes, when they shielded the Egyptian Museum from robbery and from the flames extending from the neighboring National Democratic Party Headquarters that was set ablaze during the early days of the revolution.

Despite of all this, Hassan argues, those who wish for the revolution to fail have gradually obscured the picture of Tahrir Square and the revolutionists. They succeeded in portraying them in the media as thugs and traitors, while the real criminals who brutalised them where hailed as decent citizens. Hassan cites a young revolutionary activist, sitting with him in ‘Wadi el Nil’ coffee shop, and telling the story of graffiti created by his comrades in the middle of the square, reading ‘Martyrs Square.’

The young activist recalls how someone erased the graffiti, before it was repainted once again by the revolutionists. He recalls how this paint and repaint cycle was repeated several times, accompanied with new slogans stating: ‘Down with Military Rule.’ Hassan concludes his column with the words of a young revolutionist, who tells his peers, ‘we are throwing stones at that tall palm tree, and the fruits are falling on our heads. We are so preoccupied with our injuries. We are letting others sitting in the back to step in, collect the fruits, and leave us hungry.’

The young man repeated these words to his friends, who were busy following the election results, while accusing them betraying the revolution. Hassan cites the young man’s outcry, ‘people are not treacherous, they only believed those who mutilated our image, and we do not deny our responsibility. We will soon reveal this conspiracy, and the tyrants’ feet will tremble. The important part is to self-organise, and to be up to our slogan: ‘free revolutionists

Youm7.com

With the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) set to take the presidency, at least according to unofficial ballot tallies, Mohamed Ibrahim Desouky lists a number of requests that he believes Egyptians would like to see delivered from the MB in his latest column ‘Our demands from the Muslim Brotherhood.’

As a start, the writer states the first step for MB leadership is to come out publicly and apologise to Egyptians for their silence and passivity on the issues of past. The writer recalls the clashes of Mohamed Mahmoud Street and clashes in the front of the parliament, all situations where the MB stayed silent, that require apologies. Desouky states apologising to the public might heal the pain of many who have lost loved ones.

The MB should also apologise for secret deals with SCAF, he writes. Egyptians will not accept any excuses that no deals were secured between the two parties, he writes. The writer also adds that presumed winning president should give a role to Ahmed Shafiq and other ex-presidential candidates by establishing a national accord between conflicting parties.

Desouky concludes with an optimistic request for the MB asking them to dissolve its structure. He writes the Freedom and Justice Party (FJP) is capable enough to represent the group politically and socially, where as the presence of the group will always mean that decisions are coming directly from the guidance bureau of the MB and not from the president or the government. The writer questions the bravery of brotherhood members to ever complete such dissolution of its political brand.