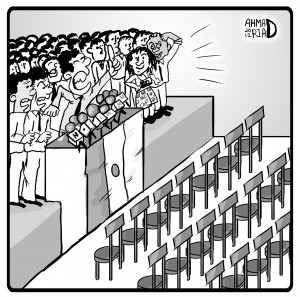

The delay of announcing the official results of presidential elections raised fears and doubts among almost all Egyptians. Questions keep popping up every morning, while Egyptians debate who will conquer the pitched battle between the two dichotomies. As Egyptians await the formal announcement of a winner in the presidential run-off, columnists in several Egyptian newspapers analysed the current political polarisation gripping a beleaguered and puzzled country. Writers also confronted wide-spread rumours about an impending civil war between political factions within the country.

Amr Ezzat

Al-Masry Al-Youm newspaper

While expecting the formal announcement of the presidential results any time today, Amr Ezzat denounced a power grab by the Supreme Council of Armed Forces (SCAF) and its Constitutional Decree in his piece titled ‘To whom goes the power.” The military’s move will undoubtedly curb the two candidates’ presidential authorities and further harms the transitional process, Ezzat writes. Ezzat noted Ahmed Shafiq and Mohamed Morsi will not be shining examples of democracy, revolution and transparent ballot counts.

Comparing the two opponents, Ezzat failed to see any redeeming qualities. From the writer’s perspective, while the Muslim Brotherhood’s Renaissance Project focuses on attempts on revitalising the country along sectarian lines, Shafiq has shown bad statesmanship with poorly spoken Arabic and basic sentence

structure, missing the elementary tool of any president’s toolbox – oratory flair.

The military coup, in Ezzat’s estimation, heightens the hurdle in the course of the 2011 revolution. If Shafiq wins, the writer assumes he will effectively subvert the uprising, embrace the military coup and lead Egypt into a ‘banana republic,’ a client state to the superpowers On the other hand, Ezzat envisions a Morsi success in the elections will trap the brotherhood into a chronic quest for survival and political recognition. Morsi and his cohorts will have to either pursue a genuine revolutionary approach or merely act the role of an acquiescent and erratic reformist organisation.

It is the military coup that, Ezzat believes, has etched a black hole in the revolutionary path. No authority will materialise with a revolutionary sheen. Irrespective of the revolution’s power in dictating discourse, the new president will have to confine himself within the boundaries set by the SCAF. The latest series of court rulings, with a culmination of a Ministry of Justice decree, which

permits authorities to stop and investigate civilians, have strangled the revolution, writes Ezzat.

Finally, the author describes those silent in regards to the ‘military coup,’ a jab at Shafiq and his supporters, as morally bankrupt and should never stand before the revolutionists and lecture them about the virtues of democracy.

Amira Abdel-Rahman

Al-Masry Al-Youm newspaper

Few hours before the Higher Electoral Committee announces the winner of presidency, Amira Abdel-Rahman in

her column ‘I quit the game’ criticises the back and forth accusations traded between the two competing

presidential campaigns. The author regards both candidates early announcement of victory as a mechanism to manipulate public opinion. She scrutinises Ahmed Shafiq’s tight-fisted clench onto the hopes of success, and similarly

chides Mohamed Morsi and his group and his threat to enflame ‘public frustration’ in case of his loss in the presidential race.

The campaigns have effectively turned an electoral exercise into a series of child-like tantrums in order to coerce their supporters. Abdel-Rahman notes that Shafiq’s campaign clings to hope of success, while simultaneously declaring victory, whereas Morsi clings to control Tahrir Square in order to manipulate public disaffection in his campaign’s favour.

The author criticises the their tactics by summarising the candidates moves as cry-baby like in that they both played ‘I quit the game’ card in order to save face. Abdel Raham’s central argument rests on the conviction that the brotherhood are attempting to strong-arm

the Egyptian public into believing that Morsi is their president despite ‘official’ results. If the Higher Electoral Committee names Morsi as president, the once-banned group will praise the transparency and integrity of the elections. However, Abdel-Rahman states that in the case of Shafiq’s success, the group will revolt against the ballot and proclaim that the elections were deliberately rigged to favour

remnants of the ousted regime.

Irrespective of the elections results, the author wraps up her article calling upon both presidential campaigns to respect the outcome and the legitimacy of elections. The ‘Revolution Continues’ is a mere slogan being parroted without a deep understanding of its significance. The revolution and its objectives cannot be sustained with sugarcoated statements lost in a pool of immature political activity. Abdel-Rahman suggests that the revolutionary thrust is pushed back in a pitched duel between the former regime

and the future theocratic state. Those who have well-digested the true convictions of the 2011 revolution

will not stray from their lofty revolutionary goals, instead, they will be co-opted into the inflammatory

rhetoric of two cry babies.

Al-Watan newspaper

Indeed, it would be a hard pill for the Supreme Council of Armed Forces (SCAF) to swallow if an Islamist president would stand in front of the room of generals who once sought to eradicate the group and incarcerate its members. Ammar Ali Hassan, in his column, ‘Morsi and SCAF’s money,’ claims the military fears an Islamist president outside the inner sanctum of the military establishment, who would threaten the military’s monopoly on political power and the country’s economic engines.

Hassan examines the reasons why the military junta does not tolerate the instability brought about by the 2011 revolution. Blood is the price the generals are willing to pay to preserve the economic benefits of their seats of power, and are managing it in the form of SCAF-led economic projects. These same reasons

are behind the military’s role in preventing Gamal Mubarak from being his father’s heir, given his appetite to privatise the public sector, which extended to include some of the businesses owned by SCAF,which, in the generals’ perspective, constitute a forbidden sanctuary.

Answering the rhetorical question, ‘why does the army hate the revolution and why does it deal with the issue of presidency in this particular way?’ Hassan remarks the idea of the military junta losing its grip on its money-making ventures and economic monopolies is what drives its anti-reformist goals. Hassan concludes his article noting that critics have always shied away from analysing the main factors of military’s hatred to the revolution. But, to be able to dissect all files relating to the sweeping political map in Egypt, one must first bear into consideration SCAF’s fear of losing its treasure chest of economic projects and SCAF-affiliated corporations.

Fahmy Howiedy

Al-Shorouk newspaper

Under the strains caused by the state-initiated plague of rumours, Egypt is now witnessing a critical stage of political uncertainty, accompanied by a widespread fear of the future held by ordinary Egyptians. In his column ‘Without mind, without ceiling’, Fahmy Howeidy analyses what he defines as the over-saturated atmosphere of Islamophobia and speculations of civil war in Egypt.

Howeidy denounces the way the authorities have succeeded in making people ready to absorb the idea that the brotherhood and the salafists would impose a strict dress code on both men and women, and would gradually arrest all artists and actors. This discourse constitutes in Howeidy’s estimation no more than

a parochial attempt to create nation-wide Islamophobia.

While Howeidy admits that these attempts to obscure Islamism in Egypt are well known, and have understandable reasons, he fails to understand are recent prognostications of imminent civil war in Egypt. Howeidy cannot conceive that authorities would not restrict the flow of some 10 million smuggled small arms into the country through Libya. While Howeidy believes that weapons were indeed sneaked through the Libyan borders on the wake of Gadhafi’s downfall, he sees the reports accusing Hamas of attempting to use these weapons to instigate a civil war in Egypt, as a pure hoax. Such reports intend to divert the attention away from the real foundations of the country’s internal instability, by transferring the problem to neighbouring Hamas, and continuing the cycle of vilification aimed at this Palestinian faction.

Contextualising this problem in the presidential elections, Howeidy examines what he describes as tabloid newspaper reports of an alleged secret meeting between the Freedom and Justice Party figureheads, where they suggested possible scenarios following the election results. The reports suggested that in the event where Mohamed Morsi was to lose the elections, 200 public figures would be assassinated by the group’s ‘death squads.’ The same report also envision that upon a possible win of Ahmed Shafiq, the military

establishment’s candidate, the brotherhood would goad Egyptians to take into the streets, while targeting demonstrators with snipers to create mayhem for the which the group could later blame SCAF.