I, like many of you, have no doubt that the revolution was a momentous point in Egyptian history. The Egyptian people have learned from their mistakes and will presumably never again accept oppression and corruption. That is all very well and good.

The revolution was not simply political, however, but tied to an intrinsic cultural overhaul as well. It is this wave of revolution-themed art, and I use the term loosely, that saddens me deeply.

I’ve been offered no less than nine distinct varieties of revolutionary bracelets, have seen no less than 14 or 15 start-ups try to cash in on the craze with new ‘Revolutionary Collections’ that consist of Egyptian flags and Bedouin-style tapestries glued to standard-issue white T-shirts.

Perhaps most disappointingly of all, I have discovered that the vast majority of recently published Egyptian literature, both in Arabic and English, has revolved around an unceasing examination of the now nearly stale revolution from every imaginable angle. It drove me mad.

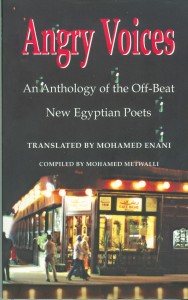

Enter “Angry Voices”. The title alone nearly drove me out of the bookstore, as by this point I plain refused – as a matter of principle – to listen, discuss, read or entertain any notions of the revolution aside from current events.

The very first sentence of the introduction, written by the translator Mahmoud Enani, reassured me. He writes “The voices in this collection are not “angry” in the sense of rebellion. In one way or another, each of these poets is rebelling against deeply entrenched customs…” I made a mental note to put Enani on my Christmas card list and plunged into the book with an open mind.

The introduction – while interesting in its detailed exploration of the intricacies of the Arabic language – is apt to alienate all but the most die-hard linguistics fans. The compiler makes an effort to draw on poems of all styles that explore many aspects of life, from the mermaids, lost loves and dreams that come standard with any book of poems to odder ones detailing meetings with Charlie Chaplin to cavemen with one testicle.

The poems in the book are delightful in many different ways. A notable one is the unique touches of Egyptian culture than pepper most of them. There is nothing quite like the sense of pride one gets when a ta’amiya sandwich is mentioned, or the toxic fumes of public transportation we all know so well are explicitly called out. None of the references are so heavy-handed so as to be overbearing, like the flags street vendors sell you at EGP 5 apiece, insisting that they make you a true Egyptian. My own recommendation for this type of pleasure is a poem called The Wall Of Genesis by famed Egyptian poet Ahmed Taha.

Another way this collection of poems is unique can perhaps be viewed as the exact opposite of the above; several poems talk of foreign concepts and places with impressive eloquence. It is a source of great joy to me that Egyptian poets can master culture to such a degree and yet not be alienated from the unique smell of foul sandwiches. Hamlet, Casanova, Marxism and Greek tragedies are all examples of concepts that purely Egyptian poets work effortlessly into their poems without breaking stride. For a fine example of this, read Troy by controversial Egyptian figure Maher Sabry.

To sum up, “Angry Voices” is one of the most eclectic and refreshing reads in the Egyptian marketplace right now. Fresh voices, fresh ideas and a fresh take on poetry as the pieces range from standard meter to prosaic poems to free verse. Make no mistake, this is no bathroom book – several of the poems have become difficult to decipher in translation. But with an earnest attempt, you will soon see they lose none of their meaning.

For a break from the political scene that all too easily engenders hatefulness and superiority, pick up “Angry Voices” and thank me later.