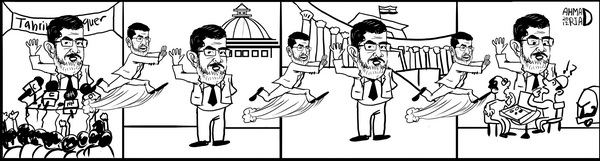

As President-elect Mohamed Morsi became President Morsi with his oath in front of the Supreme Constitutional Court, debates continued on how he would measure up to the task in front of him. Most of the recently penned opinion pieces in the Egyptian press have explored no more than two subjects: Morsi and his ties to the once-banned political group, the Muslim Brotherhood.

Columnists worried about human rights, personal freedom and minority rights under the rule of the new president, wondered if the Brotherhood would enter a phase of openness, ready to embrace competing political factions. Other opinion writers sought to debunk the claim that Morsi’s presidency is little more than a window dressing of civilian rule in a game run by the Supreme Council Armed Forces.

Salah Issa

Al-Masry Al-Youm

Salah Issa examined the lack of powers President Mohamed Morsi, whose presidential term is due to end in June 2012, unless the new constitution includes a provision extending the presidential term one year further.

Issa completely dismissed the talk about Morsi’s toothless presidency as a mere hoax aimed at gathering people in Tahrir Square in the hope of pressuring the Supreme Electoral Committee to declare the results in line with the figures announced by poll stations.

This came after the issuance of the Supplementary Constitutional Declaration, which was devised to appear as an action born out of public interests, whereas it was an outright bias in favour of a particular candidate. Citing precise clauses from the first Constitutional Declaration dated March 2012 and its addendum, Issa demonstrated that Morsi has not lost any of his powers.

On the contrary, Issa said Morsi enjoys more powers and executive authorities than former presidents Gamal Abdel Nasser, Anwar El-Sadat, and even Hosni Mubarak. Issa cynically added that Morsi will even enjoy the unofficial powers usually ceded to the president considering the ‘village norms,’ and out of respect to the ‘head of the family.’

According to Issa, Morsi possesses the authority to set out and monitor the general policy of the country and the annual state budget. He has the right to issue and even to veto legislations, and acquired the capacity to appoint and dismiss his vice president(s), cabinet members, ambassadors, governors, state employees, and part of the members of the Parliament and the Shura Council.

Issa indicated that the Constitutional Declaration grants the president the right to represent the state inside and abroad, and to undertake international treaties and accords. Nevertheless, and in preservation of the old presidential norm, Morsi retains the authority to declare a state of emergency. He even enjoys additional capacities enabling him to declare war and to instruct the army to protect the public establishments in case of instability. While these capacities are conditioned by the approval of the Supreme Council of Armed Forces, Issa attested that this has been the norm since 1948.

After the projected cancellation of the Constitutional Declaration and its addendum, expected within a maximum of six months, the liberals will ensure the new constitution grants sufficient executive power, currently absent from in their estimation, to the president.

Fahmi Howeidi

Al Shorouk

In his column, ‘They spoiled our cook!’ Fahmi Howeidi denounced the provision included in the new Supplementary Constitutional Declaration, stating that the president should take oath before the un-elected General Assembly of the Supreme Constitutional Court.

Howeidi rejected the principle whereby an un-elected body, whether the Supreme Constitutional Court or the Supreme Council of Armed Forces (SCAF), however respectable or honourable they might be, acquired posts that they now use to subjugate their people.

Howeidi challenged legal experts who wrote the provision in the declaration, and who argued the amendments were borne out of a United States style of government.

Howeidi demonstrated that although the president of the United States takes the oath before the United States Supreme Court, the appointment of members of the court is based on the condition that elected senators first must approve of the Supreme Court’s judges.

Senators are elected by their constituents, and hence represent the will of the people. As such, Egyptian legal experts ignored the fact that the judges in the Supreme Constitutional Court are appointed and not elected, and hence the element of popular will is absent.

While the British Queen is prohibited from entering the House of Commons, where only the voice of the people is to be raised, she is allowed access to the House of Lords, that is appointed according to the government recommendation. This scene, in Howeidi’s estimation, magnifies the guilt of the SCAF when its generals put tanks in front of the gates of the dissolved parliament and then similarly deny entrance to the elected representatives of the people.

Howeidi criticised legal experts who did not have a thorough understanding of the 1923 constitution, which stipulated that in case of the absence of a monarch, the senate and the parliament, even if dissolved by the previous monarch, should gather until the election of their new counterparts.

Howeidi stressed that the new ‘monarch,’ read President Morsi, will have to take the oath before these ‘dissolved’ councils to acquire legitimacy based on popular will. As taking the oath in Tahrir Square will further escalate the confrontation with the SCAF, and taking the oath before two-thirds of the parliament will not be deemed as binding; Howeidi suggested that President Morsi postpone the oath rather than taking it in the wrong place.

Saad El-Din Ibrahim

Al-Masry Al-Youm

Saad El-Din Ibrahim examined the fears among Copts, artists, Shiias, Baha’is, and women in Egypt, following the rising tide of political Islamism. Ibrahim recalled the pioneering role of an Egyptian working to draft the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948.

The Egyptian diplomat Mahmoud Azmi was a member of the Committee of the Ten that drafted the declaration, along with Eleanor Roosevelt.

Egypt was in fact one of the leading countries to sign the declaration after its approval by the last Wafdist parliament in 1950.

Minorities in Egypt, scared of losing or never gaining rights to citizenship, are threatened by the literature of the Muslim Brotherhood and their Salafist allies.

Ibrahim even added that a minorities, who more than likely did not elect Mohammed Morsi, the Muslim Brotherhood candidate, are fearful that despite gains made during the uprising of 2011 for citizenship rights that could soon disappear.

Ibrahim used a conversation he had with a Coptic woman from Qena, called Huda, who described how entire Coptic villages were surrounded and isolated by extremist Islamists during the parliamentary and presidential elections.

He also recalled the bitterness of Maximos, a Coptic monk from a Cairo slum area called Izbat al-Nakhl, who failed to convince many of the church-going Christians to reconsider their decision to emigrate from the country after the rise of the Freedom and Justice Party.

Encouraging Huda and Maximos to stand up against their fears, Ibrhaim repeated the words of Prophet Muhammad to the early Muslims struggling under the oppression of the Qurayshites, ‘Be patient o House of Yassir.’

In case the situation becomes unbearable, Ibrahim advised them to resort to monasteries in the Egyptian deserts, and preserve their Christian tolerance and their unique Egyptian culture, as they did during the Roman and Byzantine eras of repression.

Ibrahim sharef with them the words of Abdul-Rahman Ibn Khaldun in the 14th century, ‘justice between people is the basis of prosperity, and its absence is the sign of ruining this prosperity.’

Ibrahim praised Morsi, his old inmate in al-Mazra’ah prison, for hosting the mothers of the revolution’s martyrs and the figures of the Egyptian churches, on his first day in the Presidential Palace, and wished him God’s support in safeguarding the citizenship rights of all Egyptians.

Ahmed Mansour

Al-Watan News

Ahmed Mansour examined the transition as seen by the Muslim Brotherhood Society over the past 80 years. Hassan al-Banna founded the society in 1928, and established himself as the first Murshid until his assassination in 1949.

Al-Banna’s period of rule constituted one of founding and propagation, and was then succeeded by a power vacuum, which ended by the selection of Hassan Al-Hudaybi as the second Murshid in 1951. Al-Hudaybi’s period can be effectively described as the era of repression and coercion, following the Muslim Brotherhood’s numerous confrontations with president Gamal Abdel-Nasser and his regime, most notably in 1954 and 1965.

During this period, the literature of the Muslim Brotherhood called upon the brothers and sisters to show maximum patience and endurance facing torture and imprisonment, until the promised dawn of empowerment came.

In the times of president Anwar al-Sadat, the honeymoon between the state and the brotherhood did not last for long, when the brotherhood leadership were detained in 1981, including the Murshid ‘Umar al-Tilmisani, who had succeeded in the 1970’s to organize the loose knit structure of a society.

In the years that followed the assassination of Sadat, Mustafa Mashhur, Hamid Abul-Nasr, Maamun al-Hudaybi, Mahdi Akif, and Mohammed Badie; respectively succeeded al-Tilmisani.

Their eras witnessed periods of tension and some relaxation with Hosni Mubarak’s regime, until his eventual overthrow in 2011.

In Mansur’s opinion, this current stage, a former Brotherhood president in office, and an overwhelming victory of the Freedom and Justice Party in the parliamentary elections, created an entirely different set circumstances.

It is a transitional stage that necessitates the Brotherhood to reform its worldview toward openness.

The Brotherhood have for the past 60 years been operating underground, in what was a forbidden Ikhwani ghetto.

They lived with their society and for their society, and now they will have to learn how to operate a state, and live and die for the state.

The organization needs to closely examine the past failures and successes of Islamist experiences in the region, most notably Turkey, where Necmudin Erbakan failed to contain the military.

It took his disciple Recep Tayyep Erdogan to gradually confine Turkish army generals to their barracks.

Erdogan’s reformist policies launched Turkey’s economy and bolstered the ideas of Islamist reformist governments.

Perhaps Morsi will lose this battle, but a younger disciple will carry the torch much like Turkey.