Sexual harassment is a recurring problem all over the world. The blame is often directed at the woman themselves, making it harder for those affected to speak up. HarassMap is an online platform that offers women in Egypt a space to speak about their experiences and keep track of the situation, which seems to be worsening. Recently, artists and media outlets have been addressing the issue of sexual harassment more than ever before.

Sexual harassment is a recurring problem all over the world. The blame is often directed at the woman themselves, making it harder for those affected to speak up. HarassMap is an online platform that offers women in Egypt a space to speak about their experiences and keep track of the situation, which seems to be worsening. Recently, artists and media outlets have been addressing the issue of sexual harassment more than ever before.

Last year the movie 678 created an uproar because of its controversial story. The movie showed the struggle of three women from different backgrounds who were constantly facing different forms of sexual harassment. They were judged and gossiped about for speaking up, but did so nonetheless. In the movie they teamed up and devised a way to take a stand, and ended up being chased by the police for their efforts.

Last fall, there was the historic women’s march in Downtown Cairo, in response to a girl being dragged to the floor on Tahrir Square and attacked while lying exposed. The video of the attack exploded on the internet and the world saw an officer partially undressing and physically abusing her. The image of the blue bra worn by the girl beneath her modest abaya became a symbol of the systematic violence against women.

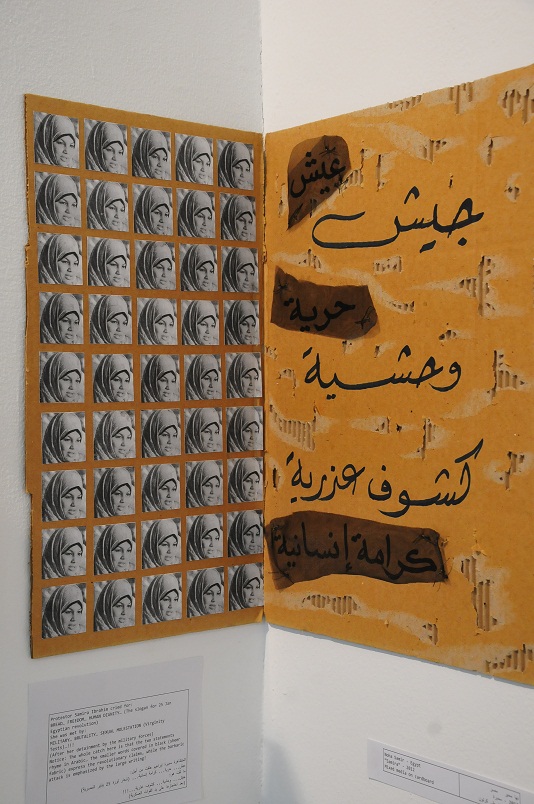

This week the ‘Harassment Exhibition’ opened in Darb 1718. The organisers invited 15 artists to create artwork related to sexual harassment in Egypt. The exhibition featured paintings, photographs, a slideshow and many other forms of artistic expression.

Habiba Sultan, one of the artists and a law student at Cairo University, explained that “the organisers conceived of the theme and invited artists to participate. It was on short notice but everyone worked hard to contribute to this important exhibition.”

Sultan’s three artworks show a woman dressed in a hijab, in a tank-top and not-too-short skirt and wearing jeans and a T-shirt respectively. The three paintings signify the way society would like her to be dressed, what her preferred way of attire would be and the compromise that most women make. “We have to dress a certain way to fit into our society” she said, “we can’t just wear what we want.”

Another contributing artist, Enas Abo El-Komsan, explained why she felt compelled to partake in the exhibition. “A woman is a human being, not a product. But she is viewed as if she is a product, something to buy, sell or try out. Harassers talk about our bodies as if they are public property.”

A long, beige dress was stretched out in the middle of the exhibition, taking up most of the available space in the room. The artist wanted to show that an empty dress is only that, and so women are not what they wear and nor should they have to wear long dresses just to be left in peace.

Another focal point of the exhibition was the screen where short sentences were projected. “I was in a cab and the driver unzipped his pants” or “the neighbor’s son dragged me to the roof when I was 9 years old” are examples of the personal accounts of the abuse women have suffered.

The exhibition was small but forceful in the combined message conveyed by the artists, that women in Egypt will no longer be silent in the face of sexual harassment.