Hayder ‘Hamzoz’ has, for more than a year, been travelling the expanse of Iraq visiting young men and women in small meeting rooms to do one thing, organise.

In the wake of bombings, kidnappings, and government restrictions on freedom of assembly and continued agitation of the freedom of the press, Hamzoz and his team of friends are not young revolutionaries in training, simply activists looking to reach their constituents in a country that seems like three separate states rather than one unified nation.

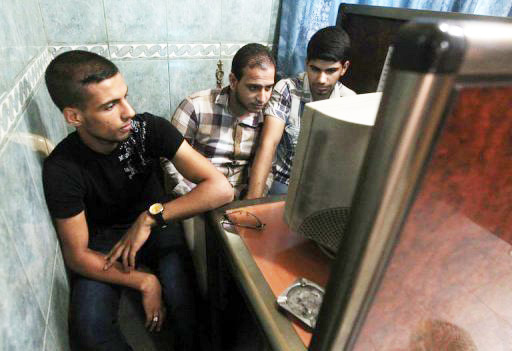

There, in the often damp, dark, electricity-strapped meeting halls, often with not enough chairs, in Kirkuk, Sulmaniyah and Najaf, Hamzoz is meeting the faces behind the WordPress blogs that crowd the Iraqi blogosphere and the administrators behind some of its largest Facebook pages.

It is these meeting rooms, where discussions revolve around grassroots activism, which the government at the behest of Prime Minister Nouri Al-Maliki is seeking to silence, along with their online debate.

Iraq’s media environment is being strangled by government overreach and outright restriction on the abilities of its citizens to express themselves online, media organisations face increased interference in their day to day operations, civil rights groups, activists and journalists note.

In June, 44 news agencies were ordered to stop their operations in Iraq, including the BBC, Voice of America and two of its largest television channels, Sharqiya and Baghdadia.

Al-Maliki’s government seems to be consolidating power by restricting the freedoms of Iraqi press and citizens.

The Iraqi government’s passage of a restrictive information law that seeks to ban freedom of expression online under the guise of protecting its citizenry, as well as orders from its Communications Media Commission to shut down media organisations based on improper licensing, are only the most recent examples of the government’s unease with freedom of expression.

The Informatics Crime Law, due for its second reading in front of parliament this month, seeks to punish citizens or entities who might participate in “undermining the independence, unity, or safety of the country, or its supreme economic, political, military, or security interests,” or “participating, negotiating, promoting, contracting with, or dealing with a hostile entity in any way with the purpose of disrupting security and public order or endangering the country.”

“Simply put, the Informatics Crime Law is a new tool for Al-Maliki and his gangs to reach his opponents and terminate them,” said Yahya Ahmed, an Iraqi who is familiar with the media landscape in some of the country’s most volatile areas.

Ahmed did not want his profession or where he is from printed in the newspaper out of fear of political repercussion.

He is, however, a reliable media source.

The vague law, and its numerous articles, “poses a severe threat to independent media, whistleblowers, and peaceful activists,” Human Rights Watch noted in an expansive report on the Informatics Crime bill.

“As a blogger I do not have qualms with the idea of the law, but I do have strong reservations, and outright objection to, the ambiguity of the law,” said Allawy Rafee, an Iraqi blogger who has been a member of Hamzoz’s training sessions.

“I’m not afraid of arrest, but I am afraid of being tried in this judiciary system.

There is no such thing as a fair trial.”