Egypt’s military has command of more than just battalions and fleets: its retired and active duty officers and generals are embedded in ministries, governorates, companies, city halls and neighbourhood councils.

Egypt’s military has command of more than just battalions and fleets: its retired and active duty officers and generals are embedded in ministries, governorates, companies, city halls and neighbourhood councils.

The military’s influence in Egypt has left an indelible mark on the form of government that could take shape following January’s popular uprising.

Out of 27 regional governors in Egypt, 17 are former military men.

Six cabinet ministers have also had long military careers (one is an active duty officer) and this is merely the tip of the iceberg with hundreds of military men holding office in the governorates, ministries, public sector companies, city halls and even neighbourhood councils of Egypt.

That is the legacy of the July 23, 1952 revolution.

The Kazeboon activist group has recently launched a new project: “3askar map” in collaboration with the group “No to the Militarisation of Civilian Posts.”

The map is an attempt to chronicle all former military men currently holding influential public civilian posts within government, local and provincial governance and the public sector.

Less than one month since launching, the group has already chronicled over 360 confirmed officers holding public office and the search is not yet over.

Over 18 ex-military men hold top posts inside the Ministry of Environmental Affairs, six in the Ministry of Transport, 12 working in parliament as well as 39 heads of local city councils and 21 heads of neighbourhood councils.

Not one of these former officers was elected.

According to Zeinab Abul-Magd, an AUC professor who specialises in the economic and legal history of the Middle East, it has long been the practice of the Egyptian military and state to reward its retired officers, be they generals or mid-level officers, with public jobs.

“Upon retiring from his post, a senior officer in Egypt’s military becomes a governor of a province, a manager of a town, or a head of a city neighbourhood. Or he might run a factory or a company owned by the state or the military. He might even manage a seaport or a large oil company. Luckily for him, he also retains his Armed Forces pension, on top of the high salary for his new civilian job,” Abul-Magd wrote in Foreign Policy.

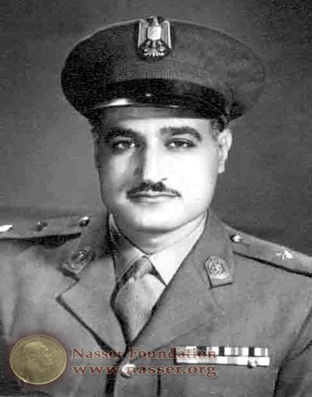

Military domination over high ranking civilian roles within the state started with former President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s coup in 1952.

Nasser, himself an army colonel, started the trend by appointing military men to the majority of cabinet posts and regional governance roles.

The practice was seen by many as one of the reasons for the 1967 defeat; however, it left the military too engrossed in running the economy and administrating the state to defend its borders.

Former President Anwar El-Sadat, also a former officer, initially started limiting the hiring of military men to political and public roles, and instead had the military focused on the upcoming 1973 war with Israel.

In the wake of the 1979 peace agreement, however, Sadat issued laws by decree granting the military wide ranging economic powers.

Ousted former President Hosni Mubarak, again a former military man, initially continued Sadat’s policy.

He started hiring military men in the style of Nasser again starting the 2000s in order to maintain the military’s loyalty as he attempted to hand over the presidency to his son Gamal.

Following Mubarak’s ouster as a result of the 25 of January 2011 revolution, the Supreme Council of Armed Forces, a military junta, took over power and wasted no time in cementing as many military men into civilian roles as they could.

“The state-owned oil sector is highly militarized, as retired generals run many natural gas and oil companies.

They also tend to control commercial transportation.

The head of the Suez Canal is a former military chief of staff.

The heads of the Red Sea ports are retired generals as is the manager of the maritime and land transport company.

In the ministry of health, the minister’s assistant for financial and administrative affairs is a retired general, among many others in the bureaucratic offices of the ministry,” wrote Abul-Magd.

“There are dozens of retired generals in the ministry of environment […] Ironically, retired officers even dominate in government bodies dedicated to oversight: The head of the Organization of Administrative Monitoring is a retired general and its offices across the nation are staffed with army personnel,” she continued.

The full extent of the rise of Egypt’s military to political and economic dominance can hardly be fully grasped in a singular examination.

For now, the numbers alone tell a daunting tale of entrenchment that warrants further examination.