On Monday in Tunisia, a crowd of Salafi men broke into a Sidi Bouzid hotel and destroyed its bar. The owner had previously complained of threats against him, even going to the police to ask for protection, but they did nothing.

The morally-charged attack comes as part of a wave of moral policing, both official and unofficial, in the Mediterranean country since its revolution in 2011 that sparked popular uprisings across the Arab world.

Amna Guellali, the Director of Human Rights Watch (HRW) in Tunisia, told the Daily News Egypt that the recent events “mean that freedoms are seeing a very big setback now. While in the first transitional moment [after the revolution] there was a flourishing of freedoms of speech, where new social media outlets were created and new laws were adopted, now we see an opposite trend.”

As part of fighting that trend, Guellali’s group recently came out with a report demanding the dismissal of charges against two visual artists whose work has been deemed “offensive to public morality.” Such an offense is punishable under article 121.3 of the Tunisian penal code.

The HRW report says that the exhibition that hosted the artwork was broken into and vandalized on 10 June, leading to riots across the country and calls from some sheikhs to kill the artists for their work. The art that sparked this: Nadia Jelassi’s depiction of two veiled women set amongst stones and Ben Salem’s work that contained a line of ants spelling out the word “Allah.”

Guellali pointed out that the new attack on freedom of expression comes in three diverse forms. First is the most blatant form, which is the physical attacks on media personnel in Tunisia. More effective is the Government’s ability to undermine the media by appointing directors of news outlets with no consultation with independent arbitrators, something that was supposed to be guaranteed in the post-revolution reforms. The third element through the justice system, such as the trials that Jelassi and Salem are currently being subjected to.

Article 121.3 has been wielded liberally to clamp down on dissents from bloggers, to television station owners, to newspaper publishers. All have been subject to jail terms or fines in 2012, according to HRW.

Ennahda, the Islamist political party that won constituent assembly elections in October 2011, says that they were not part of the decision making process that brought about the reforms, so they are not bound to implement them. Guellali said they “systematically refuse to create an independent high authority for the media. There is no political will whatsoever to create this high authority, in fact they have done the opposite, making unilateral appointments.”

This regressive use of power echoes the charges against former political aid, Ayoub Massoudi, who served as an advisor to the post-revolutionary Tunisian president, Moncef Marzouki. He is being tried for statements critical of the government and the military, which he made on his personal blog after quitting his post. Guellali said this stifling of expression is possible because the laws are too general and too broad, leading to abuse by a power structure that seems to be growing more conservative and more radical.

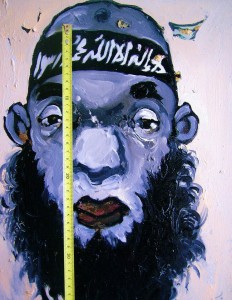

Much of the anti-Jelassi and Salem furor came from a Facebook campaign calling the two anti-Islamic. But Facebook has also been the setting for an artistic defense of the two. In response to Jelassi needing to be measured as part of a procedure when she was arrested, artists have taken photographs and created drawings measuring themselves with rulers and tape measures. Over 150 of them have been uploaded to Facebook.