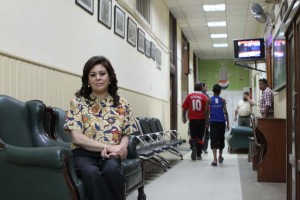

Women’s football in Egypt started in 1993 when Dr Sahar El-Hawary set up her own team. The daughter of a prominent referee, she fought against conservative values which dictated that women should not play. She said “I always dreamt of being a referee. I had patience and guts, and I accepted all sorts of sacrifices to do this.” Now head of the Egyptian Women’s Football Federation and a member of the FIFA Committee for Women’s Football, she takes a hands-on approach with the national team, attending training sessions at the national ground in 6 October City and supporting players on a personal and professional level.

Initially Dr El-Hawary sourced local talent from schools and streets all over the country, bringing young players to Cairo and providing accommodation and food for them, as well as setting up training camps and teams so they could play against each other. At first she used her own money to do this. Gradually the sport developed and grew, and by the late 1990s Dr El-Hawary’s hard work came to fruition when the women’s national team qualified for the Women’s African Cup of Nations. Now there are three leagues and nearly 20 teams. Some sports clubs are now providing coaching for five to six year old girls.

Club support

Rachel Adams / DNE

Wadi Degla Women’s Football team, based at the sports club in Maadi, is Egypt’s most successful. Three times winners of the Egyptian League and Cup and counting 12 players on the national squad, it regularly hosts friendly matches with neighbouring national teams such as Jordan, who come to train against the Egyptian club’s skilled players.

Financed by the conglomerate Wadi Degla Holding Company, which started in telecommunications and now comprises serious business interests in real estate, industrial manufacturing and private sports clubs, as well as owning two football teams in Belgium, the club also receives a substantial amount of income from sales of seasonal membership.

The sports teams themselves do not bring money in however, as women’s football is not yet considered a spectator sport, and many Egyptians are unaware that women’s football even exists, let alone that there are nearly twenty teams. When DNE watched a match at Qena, the only spectators were the hosting club’s security guards and a few locals watching over the club’s fences. Dr Ahmed Bassiouny, the team’s doctor, said, “The players are seen as publicity for the club, and as they travel around the country and abroad, they advertise the Wadi Degla conglomerate as a whole.”

Islam, culture and sport

Midfielder Nivien Gamal has played for Wadi Degla for four years. When she started playing the sport was only really for men, and it was frowned upon especially for Muslim women to play. Before she started playing she didn’t feel the need to cover her hair, but faced with comments from people who thought Muslim women shouldn’t play, she started wearing a headscarf, “to show that Muslim women can and should play,” she said.

The Wadi Degla team are treated well when they travel, enjoying five star treatment in hotels around the country and abroad. Head coach Mohamed Kamal said, “It is my job to ensure players are happy and stress-free when they play.” Although given a lot more freedom than many Egyptian girls their age enjoy, they are still protected from potential distractions – players always have to wear their strip when away with the club to stop boys from flirting with them.

The contrast between cosmopolitan Cairene players is made apparent when the team travel to places like Qena in Upper Egypt. There, where women are not allowed to be as socially active, the mere existence of teams represents a radical shift in the structure of society, as women are not only finding their feet outside the domestic environment, but they are becoming breadwinners through an entirely non-traditional form of employment.

Economic empowerment

In football’s role as a new source of income for women, the balance between religious convention and economic necessity shifts. Safia Abdel Daiem plays midfield for Wadi Degla and aims to be the first female coach of the Egyptian national team. “Women’s football is new everywhere. If you watch it in the UK, it still doesn’t get as much coverage as men’s. My family is very liberal and has always supported me, but there are girls whose families didn’t want them to wear shorts until they saw football as a good source of income.”

Mervat Abd Al-Galil was nicknamed Kawarshy as a child, after a well known Egyptian goalkeeper. One of Egyptian football’s veteran players at 32, she is coming to the end of her goalkeeping career, but for the best part of her adult life she has been her family’s key source of income. She is from Shubra, and her two brothers, their two wives, and their seven children live in their parents’ three room house there. Since her parents’ death, she has been the family’s main breadwinner and now she is nearing the end of her career, will need to diversify her skills in order to carry on earning enough money.

“I have had a very good life on my money from football,” she said. “My father always encouraged me to play, and if it wasn’t for football, I wouldn’t have had half as many opportunities,” she adds. She has been able to buy her own apartment with her wage, and she proudly shows off her goalkeeper’s trophies and the wardrobes full of clothes she has been able to buy.

Although Kawarshy is able to sustain not only herself but a family of 12 on her footballing wage, for midfield striker Marihan Yehia, 23, it’s a different story. Daughter of an economic migrant who worked in the Gulf for almost all of Marihan’s teenage years, she is ambitious and driven to carry on being able to provide for herself the same level of material comfort her mother has worked so hard to provide. Her background is different to Kawarshy’s, in that she is used to a more middle class standard of living but she makes the point that women’s wages are different to men’s, “We are called professionals, but we’re not really.

We can’t live off our wages, not like the male players. I will have to use my business degree at some point and choose that over a career in football.” Until recently, Marihan was supplementing her footballing wage with a job in telesales at a phone company. Furthermore, since the Port Said incident, football hasn’t been played at all, and although the girls carry on training, the bonuses they receive when they win a match or when they play particularly well have been suspended.

Revolution, nationalism and women’s rights

Rachel Adams / DNE

It is well documented that women have fought as hard as men in the Egyptian revolution, yet women are far from seen as being equal in the eyes of the law or society. Midfielder Engy Atteya states the case directly with regards to their status as footballers, “Our football card doesn’t say professional, it says amateur. We don’t have contracts. We compete like men do, we leave education and jobs for football. It’s still not fair.’ Schweya schweya must be the attitude however, as just by getting out on the field makes a big impact on the status of women’s rights compared to two decades ago, when playing professionally was not even an option.

Engy adds, “All girls who play football are fighting for women’s rights,” and despite women’s unequal access to civil society, Engy says she feels honoured “to represent Egypt, now that it feels like our country. Before it was the regime’s country, now it’s the people’s.” Egypt’s youngest player, Omneya Mahmoud adds that she feels part of “the new generation inspired by the revolution.”

At 17, she hopes democracy will bring new investment into Egyptian football, enabling it to compete on an international level in the future. Part of the problem with lack of investment however is the lack of television coverage given to women’s football. Many of the players complain that press only cover the sport when there is gossip or a negative story and television covers very few games indeed. The lack of media interest not only impedes financial investments, but as a result, halts standards within the game and therefore diminishes the potential of developing more and more players.

The next generation

Despite the lack of media coverage, women’s football in Egypt continues to grow. The first generation of female coaches is now working with Egyptian teams, developing a whole new generation of players and with them, the confidence and potential for self development that successful sportsmanship and financial independence brings.

Last week the first Under 17s national team’s training camp was held at the grounds in 6 October City. The players there have come from sports clubs and teams around the country and women’s sports academies. A representative from the team said, “parents are now sending their children to play, and last week we had a friendly match against Jordan.”

Dr El Hawary’s contributions to football and therefore to the status of women in Egypt as a whole are enormous. Although having tried to set up a more comprehensive sports education system in private schools around the country over the last 12 months, this has not been possible due to unforeseen circumstances, a blow for public and private schools alike shame as physical education is not always treated as an integral part of general education

Of the role women’s football plays in society now, she said “We now have 13 year old girls supporting families through football. We give her a basic education and her family treats her differently. Social change is happening within the family unit through the girl and as a result, the structure of society changes.”