8 April group

Over a year after the January 25 uprising, Egyptian organisations are working hard to free those who have been detained, tortured, and disappeared.

‘Ifrag’

Angy Naguib from the Ifrag (Release) campaign explained that it works to coordinate its efforts with others such as the No Military Trials for Civilians campaign to show solidarity with those oppressed by SCAF and free people who have been unjustly put behind bars.

Ifrag was founded last Ramadan by Salafeyo Costa (Arabic for the Salafis of Costa), a Salafi group promoting inter-cultural dialogue, and the No Military Trials for Civilians group, which has been running since March 2011. They were also joined by the Suez Branch of the 6 April political youth movement and the Supporters of the 8 April Army Officers, a movement created in solidarity with military officers who were arrested after taking part in protests. Naguib added that the most recent group to join them is the We Will Find Them campaign, dedicated to finding those who went missing in the revolution and after, which joined Ifrag on Friday 7 September.

All these organisations have come together in response to the violations of human rights which started happening very shortly after the onset of the 2011 revolution. These violations include but are not exclusive to, arrests, military trials, torture, and physical and verbal abuse. While many thought that the ousting of Hosni Mubarak would guarantee an end to state brutality, the repeated clashes that erupted after the revolution showed that violent crackdowns on dissenters is far from over.

Ever since the Supreme Council for the Armed Forces (SCAF) assumed power on February 2011, many people who were arrested were referred to military rather than civilian trials. Among the first campaigns formed in response to this, was No Military Trials for Civilians.

Mohamed Fouda from No Military Trials for Civilians said that the calls for the creation of the campaign were made in late February but the first meeting for the group was in March 2011. The No Military Trials for Civilians campaign has actively advocated for the end of these military tribunals as a “key requirement on the road to freedom and democracy.”

Fouda explained the various reasons why the No Military Trials for Civilians campaign is working with the Ifrag campaign. “There was more than one reason. Among them, was to unite the efforts of all the movements that work with detainees.” Fouda added that together the groups can achieve more work, and create more awareness as well as create more popular pressure. Fouda added that after joining the Ifrag campaign, No Military Trials will be working in parallel with the Ifrag campaign as well as carrying on with its activities.

According to the group, at least 12,000 people have been tried by the military since the start of the revolution. Yet, one of the biggest problems facing activists in such groups is the lack of accurate figures. All of the figures they have are estimates and officials are not transparent when it comes to this issue.

A special committee created by President Morsy to resolve the issue of those tried militarily has only thus far succeeded in releasing what is believed to be a fraction of the number of detainees.

‘Salafeyo Costa’

Founder of Ifrag, Salafeyo Costa, is an organisation founded by Salafis to promote inter-religious dialogue, their name playing on the idea that Salafis could never be “modern” and go to coffee shops such as Costa Coffee. The group, founded in April 2011, works on various aspects of society such as education, economic development and working with human rights organisations, NGOs and civil society organisations. They create awareness on health and social issues, provide tuition for families who can’t send their children to school, and finance small projects such as small-scale manufacturing plants.

The Ifrag campaign works on alleviating the suffering of those who have been wronged by SCAF in various ways. One of them is by publishing the stories of those who have been detained, such as Mohamed Zidan who was in a sit-in in Tahrir Square when security men showed up and told them that they were there to open up the roads for the car to pass.

Zidan was going to gather his belongings from his tent when all of a sudden, security beat the protesters so he decided to go to the tent and warn those inside. That is when he security started taking down the tents, and stepping over them. Zidan was then severely and brutally beaten more than once. He was taken to a military police headquarters where he found many others who were injured and not provided with the adequate medical care they needed. Ifrag’s motto is “we are carrying on, as long as there people in prison who don’t belong there.”

The group not only publishes the stories of the detainees but it also raises awareness on the plight of detainees through social networking sites. It also works on the ground; last month, for example, the group held a human chain for a day on Qasr Al-Nil bridge in Cairo. The participants wrapped metal chains around their wrists in a symbol of solidarity with the detainees. The group also provides humanitarian assistance to the detainees and will soon “start helping them legally in cooperation with the Hisham Mubarak Law Center and El Nadeem Center for the Rehabilitation of Victims of Violence.” Both of which assist victims of torture and provide legal assistance to them.

‘We will find them’

Nermeen Yousry , one of the co-founders of the We Will Find Them group, the most recent campaign to join Ifrag, explained that the campaign not only focuses on finding those who’ve gone missing since the 2011 revolution but also those who’ve gone missing after being randomly arrested.

This campaign was founded in February 2012 but held its first press conference in August describing its mission. The campaign says that some people who are abducted go missing for hours before they turn up while others end up missing for weeks, if not months. The campaign aims to create pressure on “official authorities who are responsible for these abductions to get them to announce the fate of those missing.”

Similarly to those tried by the military, an accurate figure of those who have gone missing since the revolution started is still unknown. “Even we, people working from within the campaign, can’t produce an accurate figure of the number of people who have gone missing,” she explained. “The number we have is from 2011 and was produced by Essam Sharaf’s Cabinet. It was 1,200, but includes those who died and those who were tried by the military. We don’t know if the numbers have risen or fallen and there is no interest in the issue.”

Similar to the Ifrag campaign, the We Will Find Them campaign is publishing the names and stories of some of the people who went missing after the revolution. “Yasser Abdel-Fattah, 17 year-old student, went missing since 19 November, 2011….. He and a bunch of friends were on their way to downtown Cairo to buy some stuff when they learned that there were violent clashes between protesters and security in Mohamed Mahmoud Street. He went to help the protesters and completely disappeared ever since. He was never found and there is no news of him since that day!”

This is just one of the stories published on the group’s Facebook page. Scanning through the stories of those who’ve gone missing, you’ll come to notice that some have been missing for over a year. For example, there’s Yasser Bakry Korany who’s been missing since 8 February, 2011.

‘Supporters of the 8 April Officers’

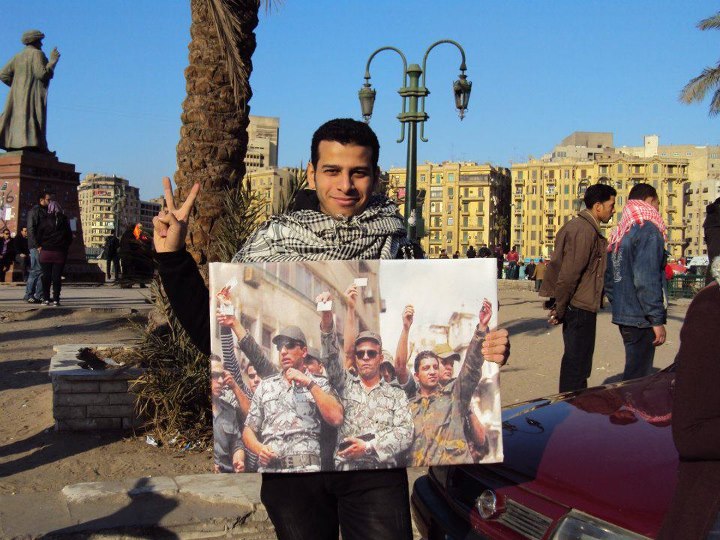

Perhaps the campaign that stands out the most is the Supporters of the 8 April Officers. This campaign is different from the rest because it aims to free military officers who were thrown in prison after having taken part in protests, some in their military uniforms.

Nisrine Yousef, an administrator of the movement’s Facebook page, said that the movement was created “right after the officers were arrested.” She says that the number of officers who joined the 8 April, 2011 protest in Tahrir Square were 21. They were beaten, arrested, and sent to military prison for their participation in the protest.

On Friday 8 April, 2011, fears had begun to emerge that the SCAF was not acting in the best interests of the country. Yousef said that the events that happened on 9 March, 2011 brought up these fears. On 9 March, the armed forces and men in civilian clothes violently dispersed a sit-in in Tahrir Square. During the violent crackdown, protesters were beaten and taken to the Egyptian Museum where they were tortured. This is part of the reason that officers took part in the protest on 8 April, said Yousef. “We were worried that the army wasn’t on our side and these army officers joined us and said, the people and the army are one hand. We just wanted assurances from the army that they were on our side.”

Yousef said that while 21 officers took part in the protest on 8 April, the total number of officers the group worked on releasing is 29, as other officers were also arrested after participating in protests in May and November, 2011. Yousef said that all except for five of the officers have been released but whenever the authorities are asked about the remaining five they don’t give clear answers. In a recent protest in front of the presidential palace, “one of the officials came out, when we said that we’d handed in papers regarding an officer, a month ago, he said, we only learned about it last week.”

The Supporters of 8 April Officers helps raise awareness about the officers on the ground by holding demonstrations and handing out brochures and stickers. Youssef said that the group is gathering one million signatures for the release of these officers. “We will send these signatures to the president and to SCAF.” One copy will be sent to President Morsy and the other will go to Major General Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi, Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces and Minister of Defence and Military Production.

Yousef says that the level of awareness and interest in the issue of the 8 April officers has risen. “At first, we had to go and explain to the people who they are and tell their stories. Now, when we go tell people about them, they know them and they immediately start asking whether they’d been released or not.” Yousef added that the families of the officers along with the help of lawyers are trying to create pressure in order to see to the release of the officers.

‘Try Them Campaign’

The Try Them campaign, launched earlier this year, demands the trials of the heads of the former regime in a special court which would be set up based on a revolutionary justice bill which members of the campaign themselves have prepared.

“People who have committed crimes between 1981 up until the election of Morsy will be tried in that special court based on that bill which we managed to get into the People’s Assembly through the Member of Parliament Mostafa El-Nagar (although the People’s Assembly was dissolved a few days after),” said Higazi.

The coordinator of the campaign, Heba Higazi, explained to the Daily News Egypt last month that the campaign was launched in response to President Mohamed Morsy’s decision to sack five top military leaders; including former Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, Hussein Tantawi and former Chief of Staff, Sami Anan who were both awarded Egypt’s top state honours, the Order of the Nile and the Order of the Republic, respectively, last month.

Ahmed Ragheb, co-founder of the Try Them campaign and one of the people who has made a great contribution towards writing the revolutionary justice bill explained their initial target of five ex-regime members is just the beginning of an expanded campaign that will target more individuals.

The Try Them campaign takes issue with the way former regime heads are being tried and calls the trials “plays”, Mubarak, for example, is being tried for crimes committed in a short period of time rather than for the entire 30 year period he ruled for.

‘No Safe Exits’

This campaign is an offshoot of the Try Them campaign and calls on people to send messages to Morsy and it even suggests texts such as “no to the safe exits of Hussein Tantawi, Sami Anan, Mourad Mowafi, Hamdy Badeen. No to the safe exits of those who killed the Egyptians.”

The campaign called on Morsy to publicly apologise to the victims of the violations of the former regime and to offer guarantees that those responsible will be pursued. It also called for the withdrawal of the “state honours given to some military officials who have taken part in killing Egyptians.”

‘Katheboon’

Another campaign called Katheboon was created after the events of the Cabinet protests. It calls itself “one of the engines of alternative and popular media.” The campaign uses alternative media in an innovative and engaging way to expose lies made by the military.

Katheboon is Arabic for liars, and it is said in reference to top military officials. The campaign calls on anyone who has videos or pictures that can expose the lies of the military to contribute to the campaign. The campaign played videos and images on the streets and in universities and invited people to host their own similar events using the name of the campaign to expose violations and lies committed by the military. It started in December 2011 reached its peak with over 150 events in January 2012.

Arrests, beatings, torture, and deadly crackdowns on protests were not what Egyptians were hoping for or expecting after the 2011 uprising. Some may say that the momentum of the revolution is dying down but there’s still a few who take out of their time to take to the streets, to stand up for someone or to organise a campaign to fight for justice.