Hassan Ibrahim

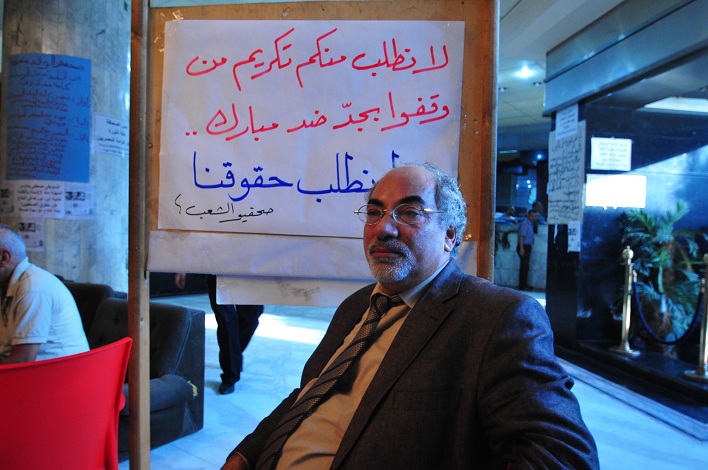

Former journalists of Al-Shaab newspaper are set to begin a hunger strike on Sunday, in order to pressure the current government to meet agreements made under the Mubarak regime.

The Egyptian Press Syndicate’s council held an emergency meeting on Wednesday night to discuss the sit-in held by some members of Al-Shaab newspaper at the syndicate’s headquarters.

The council declared complete solidarity with the striking journalists, who are demanding that an agreement signed with the syndicate in December 2009 be upheld. The agreement was witnessed by several heads of national, partisan and independent newspapers, and approved by the Shura Council.

In 2000 the Egyptian Labour Party ran into trouble with the Mubarak government and was subsequently shut down, along with their newspaper Al-Shaab. After the January 25 Revolution some of their members formed a new party, “The new Labour Party” and a new paper was issued.

According to Diaa El-Sawy, a reporter for the new Labour Paper and Deputy of the party’s organisational committee, some of the reporters from the old publication struck a deal with Makram Mohamed Ahmed in 2000. In return for positions within other state-run publications and some financial remuneration, the reporters agreed to support Ahmed in his campaign for a position in the syndicate elections at the time.

“We do not have the same demands as the reporters protesting, but we do support them because it is their right,” said El-Sawy.

Despite 14 separate court decisions to uphold the agreement, former president Hosni Mubarak circumvented the courts and refused to grant the journalists any compensation. According to the former deputy editor in chief Talaat Romaih, the first protest and hunger strike held in 2000 resulted in a court decision guaranteeing that the former employees of Al-Shaab would keep receiving their paychecks.

Six months later however, the general staff of the paper stopped receiving their paychecks. The journalists continued to receive their pay, but the government closed the paper’s insurance file.

“We have four demands of the government,” Romaih said. “Re-open the insurance files, increase the pay of all journalists and employees of the [former] publication, full compensation for the past nine years and guarantees of positions within other publications.”

The council stressed to the syndicate the right of Al-Shaab journalists to have the agreement implemented in full, without the need to negotiate a new agreement.

The syndicate board made an urgent request to have a delegation comprised of six syndicate council members and three Al-Shaab journalists meet President Mohamed Morsy, in order to persuade him to issue a presidential decree enforcing the agreement.

The Press Syndicate also issued a separate statement the same night, stressing the following demands to be included in the new constitution: The abolition of imprisonment regarding all publication-related issues; the abolition of any and all legal provisions surrounding the closure of a newspaper whether through an administrative or a court ruling procedure; clear legal provisions regarding the independence of the National Press Council from the state authorities and political parties henceforth; guarantees surrounding the independence of national press institutions and all media owned by the Egyptian people; and the adherence to the constitutional article which states the press is a public authority.

Confronted with the possibility that Morsy may not rule in their favour, Romaih insisted they would continue their hunger strike “until the death” if need be.

Khalid Youssef, the vice president of the former Al-Shaab, explained how their protest represented more than the demands of a few journalists. “In the past we were very aware of who the enemy was,” Youssef said. “We were ready to sacrifice ourselves to get our rights or to bring down the old regime, but after the revolution the old enemy was gone, and we remain unsure if the current state is an enemy or a friend.”

According to Youssef there is one important question the state must answer, “fail or succeed, is this immediate state also an enemy of the people and their rights, or will they support the people and their rights?”

“This case is about the rights of workers, but in its core it is a battle for people’s rights to have access to information.” Youssef said.

For Youssef, Morsy’s decision on the matter will be a strong indicator of Egypt’s press freedom. He sees the process by which the state has treated the journalists as proof that they operate using methods. “The first thing we must change is the meaning of state,” Youssef continued, “ from the authority of ruling to the authority of serving the people as Morsy pledged he would.”