Violence in the city

On 27 October, a mob of people in Talaat Harb square accused a Sudanese man of espionage and assaulted him. The mob accosted him and his two female companions for what he has described as nothing more than a racist attack.

Ibrahim Musa is a 27 year old Sudanese man who has been living in Cairo for over nine years. Born in Darfur, like so many other Sudanese people he left seeking a safe haven elsewhere. Musa does not consider himself a refugee but has shared the same burdens as those who have escaped the violence at home, only to find themselves in a different battlefield.

“I was passing through Talaat Harb square with two foreigner friends,” Musa recalled. He and his friends were buying some last-minute things because one of them was set to go back home. “As we were crossing the square a group of men approached me and grabbed me by my shirt. They began accusing me of being a spy and asked if I worked for the CIA.”Ibrahim’s friends tried to get between him and the rapidly growing crowd. As the crowd grew larger and the attackers became bolder one man grabbed Ibrahim by the shirt and ripped his collar. When people began to accost his friends some members of the crowd tried to help them, whilst others tried to hold them back. “The crowd began arguing with themselves and quickly turned to violence,” Ibrahim explained. “In the confusion someone grabbed me and my friends and pulled us out of the crowd.” Musa fled the scene with his friends and managed to avoid being caught by his pursuers, but not before taking a beating. Ibrahim could not be certain of how many people were there, but he believes the number was over 100.

Ibrahim faces incidents of discrimination everywhere he goes. When catching the metro, he is often stopped by security guards and questioned about his movements. On more than one occasion, ticket vendors in metro stations have shut the booth in his face and refused to serve him.

“They never show us respect, and are always suspicious of me because I am black and from Sudan,” Ibrahim explained. He is often ignored at restaurants, supermarkets and bars. “The other day it took almost three hours for Gad to make my pizza. Everyone else had their orders made and I asked them several times and they told me to wait.” A bartender once called him a slave.

“I am a Sudanese man living in Cairo and nobody cares about us. I don’t feel safe here in Egypt and every day I am a victim of racial abuse. If the government does not care about their own people, how can they be expected to care about us?” In July Ibrahim was attacked by a pack of young men who beat him up and stole his money in Abbaseya. “If the police had not disappeared after the revolution,” Musa explained, “then maybe these things would not happen so often.”

Ibrahim’s tale is not uncommon. Sudanese refugees are all too often forgotten by the very organisation which has sworn to protect them; the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Refugees have a particularly hard time finding jobs and a place to live due to bureaucracy and discrimination. One refugee was in need of eye surgery, but did not have the money to pay for the tests and operation. Her family was very poor and lacked basic amenities in her temporary home.

Ibrahim has met and worked with many refugees in Egypt over the years and has come to the conclusion that the UNHCR and the Egyptian government do not care about these people. “They came to this country seeking peace and found instead a big problem,” Ibrahim said. “They were fighting to live in Sudan, but here we are all living to die.”

The revolution has in so many ways brought about tremendous change, but this transformation has not always yielded immediate positive results. The disappearance of police officers after the initial phase of the revolution created a massive security vacuum, which has been one of the biggest concerns Egyptians have voiced over the past 21 months. Less security has led to the rise of violence and assaults in busy city centres. Crime in Talaat Harb, Cairo, has escalated since the onset of the revolution. Many Sudanese and South Sudanese have expressed their fear of the rise in crime in the area over the past year and agree that under Mubarak, personal attacks were not as frequent. Christopher Mohamed, whose parents are from Sudan and South Sudan, came to Cairo four years ago to study at Cairo University. He said that under Mubarak, the baltageya (thugs) were not out on the streets targeting Sudanese people as often as they are now. In August, Christopher was assaulted in Benisrayat by a group of men with knives. “They called out to me, and called me ‘Zol’ [Sudanese for ‘buddy’],” he said. The men were Egyptians and had recognised him as being from Sudan, by which point they approached him and threatened him with a knife. “I gave them everything I had, what else was I going to do?”

Police

Going to the police has often been out of the question, simply because many victims of discrimination feel they will not receive the justice they deserve.Under Mubarak the police presence was a deterrent for criminals who had no allegiance to the government or the security forces. When it comes to reporting crimes or seeking help, many choose to keep quiet. “The authorities look at us as if we were the perpetrators,” a young Sudanese man told me as we wandered through Cairo. “I dress nice, my beard is trimmed and tidy, do I look like a criminal?” All too often the answer is apparently “yes.” Not long after, as we sat down for a drink, the waiter handed a menu to me and wandered away. The look on my companion’s face revealed no surprise, as he stared down the other waiters and called for a menu. When the bill arrived it had been conveniently divided in two, without anyone being asked.

The crackdown on protests and the house searches in Sudanese neighbourhoods over the past decade has left many Sudanese torn; on the one hand security forces were often the source of their harassment, yet on the other hand the alpha-bully on the playground kept many other bullies at bay. The events that befell Ibrahim and Christopher over the past few months are testament to the growing levels of violence prevailing in the streets in the absence of security.

Women

Sudanese women are harassed daily; from catcalls to physical struggles, sexual harassment is one of the biggest problems facing women in Egypt. Many Sudanese women have said that the issues surrounding gender discrimination have affected them much more directly than any of the issues surrounding their ethnicity. Nevertheless, even within the context of gender discrimination the issue of race can creep in.

Former AUC student, Termikerlyn Black, pointed out that the attitude of the people on the streets is a reflection of the government’s relationship with African nations in general. “There is an identity crisis in Egypt,” she said, “Where they are not sure if they are African or Middle Eastern without realizing they can be both.”

Termikerlyn argued that Morsy’s recent attempts at normalising continental relations was the first step in the right direction for Egypt. Morsy’s visit to Ethiopia, one of the sources of the Nile and one of nine countries whose legal rights to the Nile water is dwarfed in comparison to Egypt’s 50 percent share, is a positive sign that Egypt is ready to re-assess its relationship with its war torn neighbour.

The scars of half a century of warfare

Sudan’s two civil wars left an estimated two million dead, through starvation, disease and war. Most of those that were killed were civilians; ordinary men, women and children caught in the crossfire between government troops and separatist forces. The wars left Sudan a broken shell of its former self, divided in two and still struggling with internal disputes.

The first civil war was fought from 1955 to 1972, with media outlets reporting half a million deaths. The struggle for the future of the nation remained officially in cease-fire for 11 years, when the Sudanese government and the largely united southern separatists signed a peace accord. In 1985, a military coup deposed the president and held new elections the year after. The next 20 years saw a period of increasing violence and a mounting death toll. The United States Committee for Refugees (USCR) estimated in 1998 “at least one out of every five” South Sudanese had died due to the civil war and as much as 80 per cent of the southern population may have been displaced at least once. “The massive loss of life in Sudan far surpasses the death toll in any other current civil war anywhere in the world,” USCR said, while Sierra Leone, Georgia, Kosovo and Algeria’s civil wars raged.

The end of the war in 2005 was brought about after years of negotiations between southern separatists and government diplomats, with the help of the international community. The separatists received six years of autonomy under the new accord, which guaranteed them a referendum on secession by the end of that period. Last year’s referendum passed nearly unanimously in favour of secession from the north and the Republic of South Sudan was officially born. Despite the split, conflicts within each nation and cross border incursions by both government and armed gangs has kept much of the conflict alive, with areas such as Darfur in Sudan still operating under a state of civil war. When the war officially ended in 2005, the death toll was believed to be as high as two million

Refugee rights

Living as a refugee in Egypt has not been an easy task, for the Sudanese that come to Egypt seeking protection from persecution justice is often found wanting. Over past decade there have been several demonstrations led by Sudanese immigrants and refugees demanding better treatment from authorities and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). There are just over 10,000 Sudanese refugees registered in Egypt, according to UN statistics. The statistics also show that every one of the registered refugees receive assistance from the UNHCR. Nevertheless the total number of unregistered Sudanese fleeing violence in the north and south is unknown. The Africa and Middle East Refugee Assistance charity estimates that the total number of refugees and asylum seekers in Egypt may exceed half a million, with most of them coming from Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea and Somalia.

The UNHCR is hopeful that due to the recent independence of South Sudan, refugees may soon begin to repatriate, but for many Sudanese refugees in Egypt returning home the near future will not be possible.

“Over the past few years UNHCR has tried to shift from providing individual refugees with assistance to helping them become self-reliant, including through vocational training and the provision of microcredit, employment services and counselling,” the UNHCR reported on its’ website. “However, the lack of a legal asylum framework, high unemployment and widespread poverty among nationals, as well as limited opportunities for refugees in the informal sector, remain major challenges for UNHCR in this urban-refugee situation.”

As a Sudanese political activist by the name of Hassan told the Daily News Egypt in September, it had been eight years since he first applied for refugee status, and no official status has yet been granted. “I still carry a yellow card,” Hassan explained, “but I am not yet a refugee.”

Adam Ishak is a refugee, who has spent the last 11 years of his life in Egypt. Adam is faced with discriminatory and often aggressive behaviour almost daily, and has often had the justice system swing against him when dealing with authorities. “When I get in trouble with people because they are rude or racist towards me,” he said, “other people stare at me with disapproval. ‘Stop making trouble’ some say, others just stare at me.”

Adam participated in the 2005 demonstration outside the UNHCR to protest the change in the UN’s refugee system. Prior to 2005, cases had been handled on an individual basis since 1995, but in 2005 they decided to issue ‘yellow cards’ which provided only temporary protection but no refugee status. The protesters demand more rights and recognition, and camped out en-masse for three months outside the UNHCR building.

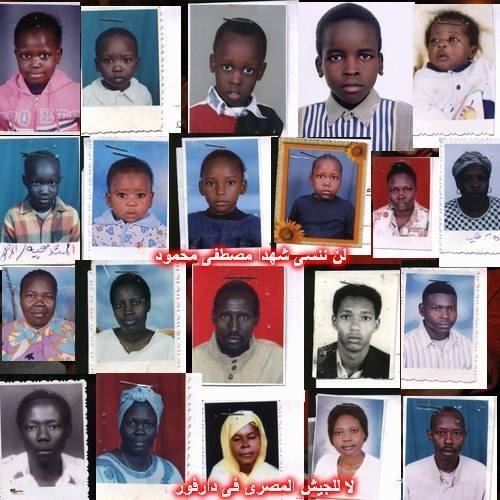

The protesters were met with water cannons and a legion of security forces. Before the eyes of the world and those responsible for the safety and security of refugees, the police raided their encampment and left at least 25 confirmed dead, many of which were barely teenagers and a disproportionate amount women.

Adam would not elaborate on what he had experienced, but suffice to say he “will live with it forever.”

Ibrahim Musa was also present in the clash, and spoke of the violence that had been carried out upon them with no impunity. “There were thousands of us there,” Ibrahim explained. “When the police came they came with force.” He saw women and children dragged from the feet and hair by security forces, kicking and screaming. Police officers beat protesters to submission, and many to death.

“We wanted recognition and fair treatment from the world,” Ibrahim explained. “Even now, the children of Sudanese people that are born here do not receive residency.” He is not a refugee, in large part because he has never wanted to be registered. “The [UNHCR] can’t help us, it is a waste of time because there is nothing they can do.” Ibrahim has worked extensively with refugee communities in Cairo, and over the past ten years has seen, heard and personally experienced countless acts of discrimination performed by the authorities as well as the wider community.

“In 2009, I think they went back on that decision [to end individual interviews] and started to conduct some interviews and granted a blue card to those in need or with dire medical needs,” Hassan told me, “however, the percentage is tiny.”

Many Sudanese refugees are reluctant to speak about their rights; some fear retribution, others have had difficulty sharing their experiences in Egypt and the discrimination many face on a daily basis. Therefore some of the above names have been altered.