Marwa Abbas

For the past decade in Egypt, the mainstream music business has been strictly imposing creative control on the music it sells. Creative control and market forces contradict the basic notion of what music is for many struggling Egyptian musicians.

Not only does the mainstream market shackle artistic expression, but the final product is deemed by independent artists as worthless product that follows a template. “Since the 50s, all songs have been about romance,” said Tamer ‘Tousy’, an independent musician. But lately, Tousy feels that a puerile version of romance has started to dominate popular lyrics and music. Tousy believes that the underground music scene presents a more honest expression of the reality of life.

The underground scene in Egypt is a subculture that includes independent artists, a knowledgeable audience, supportive venues, gigs and festivals that present and promote music that is not subject to creative control. The scene embraces genres like rock, funk, jazz and latin presented through English or Arabic lyrics. Through instrumental and lyrical songs that tackle several issues in a broad palette of genres, the underground scene presents artistic diversity, with all the members agreeing on the freedom of artist expression.

“Today, the only mainstream artist who is not severely limited in the messages or the music delivered, is Mohamed Mounir,” said Tousy.

Mohamed “Jimmy” Jamal, vocalist in the band Salalem, does not wish the mainstream scene to be buried, but he wants a fair competition. “Just give us the same support and opportunities then let the people choose”, he said. Though the scene has grown during the past decade, it is still small in scope in relation to the population because not everyone knows about it yet.

Underground musicians cannot depend on music as a livelihood. Though Ammar Yasser Kamel is a marine engineer, he dreams of pursuing a musical career but he cannot achieve his dream because he cannot depend on music alone. “I could have become really famous and rich if I had agreed a few years ago to compose music for songs that say ‘I love you’ and ‘she left me’,” said Ammar. But he refuses to engage with the rules of the mainstream business, in return for money and fame, because he could no longer consider himself as an artist.

This is the quandary that faces the many musicians within Egypt’s underground scene, and the financial obstacles facing underground artists are related to the venues, events and the culture of music in Egypt.

Where to play

There is a lack of venues in the country for live underground music. Currently, the two major venues promoting independent artists are the Cairo Jazz Club and the Sawy Culture Wheel, in Cairo. Other venues include Makan, and seasonal performances at El-Genina Theatre (also in Cairo) and the Alexandrina Bibliotheca.

Hany Mustafa, who performs with his rock band Egoz in addition to his solo project, is frustrated by this. “We do not have venues, there are no venues, we are kidding ourselves,” said Hany.

Artists like Hany, wonder why investors are unwilling to establish more music venues. “Any investor could make a lot of money out of this gap in the market,” he said. Musicians are puzzled by the lack of investment and financial support, Hany believes that nobody considers supporting the underground scene because it is not taken seriously, but others cite economic factors.

Ammar said that after the January uprisings in 2011, some venues and event organisers approached underground artists for performances, but for much lower fees than usual and sometimes even for free. “They justified their request by not having enough money,” said Ammar. Artists that agreed to perform under the new conditions did so because they were desperate to perform. But since then, Ammar thinks that most of the venues have taken advantage of the situation. “And then you discover that they [organisers/venue owners] have made quite a lot of money from our performances,” he said. Musicians know they are being taken advantage of, but there are no options available for them. “It is like we are feeding on crumbs off the table,” said Hany.

The venues have the musicians over a barrel, if a band refuses to perform on account of the small fee or professional dispute, “venues can always replace that band with another group who just want to go on stage” Hany said. Ahmed Nazmi, a prominent bass player on the scene, believes that most venues do not consider the quality of the music and they just want to maximise their profit. The low standard of music offered up at the venues is a common gripe of the musicians, “anyone gets to form a band and perform on stage, and there is no quality control from the venues” said Nazmi.

As a jazz artist, Nazmi believes that instrumental bands are even more marginalised. He respects Makan, a music venue, but he said that other venues have been approaching jazz bands with a vocalist in their line up rather than instrumental bands. “The public cares for the lyrics in the song and not the quality of the music,” said Nazmi.

“It is a matter of education and culture,” he said, but even though more space is available for commercial artists, cover bands, or any underground band with a vocalist in their line-up, language is another obstacle faced by vocalists.

While bands like Salalem and Massar Egbari sing in Arabic, artists singing in English face a language barrier. In addition, vocalists are criticised for singing in English, especially by industry types.

Hany was at Mazzika TV station, applying for a job, when one of the staff mentioned that Hany had a good voice. Sat nearby was a renowned lyricist in the commercial scene who requested Hany sing, so he sang a song from his band Egoz. “I remember their reaction, they were extremely interested,” he said. But as soon as he was finished, Hany was taken by surprise.

Sally Fakhr

“It is something that never came to my mind, but I should have seen it coming,” he said. The lyricist asked if Hany wanted to sing the song in Arabic, and Hany replied, “It could happen, but I do not want to.” The rhythm of the vocal line depends on the lyrics being in English. The lyricist told Hany not to worry about it, and that he will write it in a way that works out fine, but Hany refused. “It could have worked out, maybe,” Hany said, “I was stubborn about it, because I didn’t want him to do that.”

Hany is not in love with another language just for the sake of it, English is a language that he believes everyone understands, and even those who do not speak it well can at least figure out a word or two. “If I sing in English, I do not threaten someone’s culture,” Hany said, “those who criticise me for singing in a foreign language wear jeans, and knock off jeans at that, so end of discussion.”

The trouble with unions

While musicians struggle to achieve their dream, an unexpected obstacle exists in the form of the Syndicate of Musical Professions. “If I am a musician watching my friends perform at a venue, I could get into trouble if I was invited on stage just because I do not have a syndicate card.” said Ammar.

In Egypt every Egyptian musician has to be a member of the syndicate if they want to perform. At his friend’s wedding Ammar and other musicians wanted to perform a specially composed song for the groom, but they were not allowed to go on stage because they did not have syndicate cards. “We just wanted to perform this song for him as a gift,” said Ammar.

A musician can be an active or an associate member at the syndicate and an active member receives pensions, insurance, and compensation in case of unemployment. But Ahmed El-Haggar, vocalist and producer, wonders why it is mandatory for a musician to have a syndicate card. He believes that the syndicate should understand the meaning of independent art and musicians should understand the function of the syndicate.

Acquiring a syndicate card does not seem to help musicians. Despite an annual membership fee, the syndicate approaches musicians at their performances to collect a percentage from the band’s payment. “I consider this whole syndicate issue as extortion,” said Tousy – Masar Egbari’s drummer. The band was performing at a private event in a hotel, when a syndicate official suddenly approached them and asked them for money. “I do not get it, we already pay taxes,” he said “are we supposed to pay taxes and pay money for the syndicate as well?”

Jimmy said that the syndicate just estimates a performance fee for the underground bands, which bears no relation to the actual amount that the band takes at the event. Salalem were performing at an event in Porto Marina, and they were shocked when the syndicate official approached them, asking for EGP 3,000. “How many thousands are we getting as a band to give him that amount?” asked Jimmy.

Ehab Sayed Abdel Rahim, head of Egypt Copyright Centre said “The syndicate collects fees without any laws supporting their actions.” According to the law, the syndicate supervises the execution of a contract in return for a percentage of the money. If a band signs a contract with a producer and fears being cheated, then the band seeks help form the syndicate.

The syndicate observes the signing of the contract, and follows up with the other party to ensure that the contract is adhered to. In return for this, the syndicate collects a percentage from the money received by the band. In the case of an active member, the fees collected constitute two per cent of the money, and 10 per cent in case of the associate member. “If the band or the musician do not request this contractual service, then the syndicate is not allowed to collect any money,” said Abdel Rahim.

Events: Gigs, Concerts and Festivals

Underground bands do not perform enough gigs throughout the year, mainly due to the lack of venues. Events held by independent organisers try to compensate for the scarcity of venues, but times are hard. “There are not enough major events as there used to be,” said Ammar.

In 2006, Mohamed Lotfy – commonly known as ‘Ousso’ – established the SOS music festival, which took the underground music scene to a completely new level. Ousso, was not only an underground guitarist and a producer, but was also well recognised in the mainstream business.

He understood the underground music scene and what it deserves, so he formed a music festival that took place every three months and lasted four years. The festival gave underground artists the opportunity to perform to a growing number of audiences.

Since the early 2000s and before the SOS festival, underground concerts attracted a couple of thousand people at most. But starting with its first festival, SOS attracted 8,000 people which grew to almost 25,000 in the next few years.

Ammar wonders why there can’t be festivals, like SOS, that promote underground musicians in post revolutionary Egypt. He thinks that organisers fear spending money on underground festivals, but is sure they would be successful.

One festival that emerged after the January uprisings was the Street Music Revolution, founded by an underground guitarist, Sherif Galal. The first time the festival was held it was funded by small contributions from underground artists and held at Marghani Street, in Heliopolis. Only a few people, mainly friends of the performing musicians, attended the early shows, but by the end of the first day the streets were packed with an interactive audience. People in the surrounding buildings came out into their balconies to watch the performances.

Underground festivals have been proven to attract large audiences in the past five years. Ammar said that people often attend who are not familiar with the music, but when exposed to it they love it. The degree of public exposure depends on the opportunities given to the independent artists. “But how do we appear to the people and what should we do?” asked Ammar.

The Street Music Revolution and SOS are not the only festivals founded by independent artists. In an attempt to promote jazz in Egypt, jazz artists Amro Salah, Samer George and Ahmed Harfoush founded the annual Cairo Jazz Festival in 2009.

The few venues that host underground musicians are starting to hold festivals that promote local talent. For instance, the Cairo Jazz Club organises the Art Beat Festival for world music. But besides the Jazz Club, generally, musicians cannot hold festivals at their own expenses, or even organise them frequently. “My job as a musician cannot be thinking creatively, writing music, rehearsing, practicing and performing, in addition to organising events,” said Ammar. “What do event companies do? What does the Ministry of Culture do?” asked Ammar, bemoaning the lack of support for underground artists.

Nazmi acknowledges the ministry’s efforts in promoting classical music, classical Arabic bands, ballet, opera and folk music. But he wishes the ministry would provide special programmes that recognise the underground scene because currently, “[the ministry] consider us as nothing.”

The culture ministry does run a festival called Citadel, which features many musical arts, as well as underground bands.

Ammar also believes that the underground scene in Egypt deserves more attention, because of its depth of talent. He pointed to the Middle East Bed Room Jam, a music competition run by Red Bull. Out of the top eight on the competition’s buzz chart, seven bands were from Egypt. For Ammar, this proves that local independent musicians can attract large audiences.

Recording

Underground musicians are constantly frustrated by obstacles preventing them from recording their work to the standard they desire. Unable to sign a recording contract because the local music industry is hostile to them, they are forced to finance their own albums.

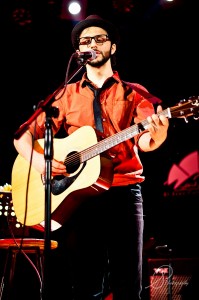

First they need to generate money from their performances but because independent artists cannot depend on gigs to finance their record production, they usually need to get another job. “Musicians have to juggle everything and work 24/7 just to finance this dream” Hany said, “this dream we have had since we were kids”.

Independent artists do not seek funding from mainstream production companies because music executives and music producers in Egypt rigidly follow market rules of mass production, to an extent not seen in Europe and America. Quite literally, they use the same music and the same lyrics in every song, with only the most tiny variations.

If Jimmy and his peers were to go mainstream, producers would control the music as well as the image of the artists. If Music is about artistic expression, underground artists cannot subject their art to the vagaries of commercialism.

Self-funding a record hinders a band’s career progress, but Maleleem have an advantage because Ammar owns a studio, which facilitates the recording process at a lower production cost.

Hany is working on releasing a new album, following the release of his EP. In addition to recording the album at his own expense, Hany hardly finds any time to sit and work on his music. “I have to work in the morning and at night, to collect the crumbs,” he said, “to spend it on [the record]”. But he feels blessed to be surrounded by supportive people within the scene, in his performances and especially during the production of his record.

Sallie Pisch

There is a sense of mutual understanding within the underground scene. Whether it is session-musicians or sound engineers, everyone understands the situation of a fellow musician who feels compelled to release a record. For instance, the audio engineers working with Hany have postponed the payment of fees to ease any financial burden. Ismail El-Ghareeb and Mostafa El-Kerdani, bassist and drummer respectively, recorded their parts without asking for a payment.

Fortunately, there are some artists who have managed to receive financial support from bodies that are interested in promoting the underground scene. For instance, Massar Egbari are about to release their self produced album, financed partly by Mohamed Hefzy – the cinema producer and scriptwriter.

A regional non-profit association, called the Culture Resource, provides production grants to independent artists to record their music. Eftekasat, a renowned local instrumental band, has benefited from a $3,500 grant from Culture Resource to record their first album, Mouled Sidi El-Latini. However, the budget spent on the album was $11,000.

Nazmi is releasing an ethnic jazz record, titled Ithbat Hala (Stating a Condition). He did not seek the help of Culture Resource, because he said that their grant would have only covered 10 per cent of the record’s budget. A Lebanese association called Afaq, which covered around 85 per cent of the album’s expenses, funded Ithbat Hala. Nazmi covered the rest of the expenses himself.

Though Nazmi was fortunate enough to find funding for producing his record, distribution remains a problem. So far, Nazmi is expecting to cover the distribution costs at his own expense. He is currently in negotiations with an international company that has agreed to cover the distribution process, on a global level. He’s prepared if he has to distribute it at his own expense, “I will release the album online, on itunes for example, and sell the physical album at my concerts and gigs only.”

Integrity

Nazmi believes that the mainstream music scene in Egypt does not promote art, but it destroys it because people are caught up in a struggle of how to generate money. “It is impossible to make money from presenting respectable art,” said Nazmi. Musicians call for more support to be directed towards the underground scene, as it embraces diverse music and talent. “This is what I believe I was meant to do,” Hany said, “even if no one understands it, it is a dream.”