Sarah El Masry

Old Cairo is home to the famous Magra el-Oyoun aqueduct (dating to the 16th century). Although it contains many Coptic and Islamic sites popular with tourists, it is also one Cairo’s poorest neighbourhoods. It is overpopulated, but vibrant with different crafts and small industries. It has an area called el-Fawakhreya designated for pottery workshops, another, el-Madabegh, for leather industry, another for car workshops and some for glass cutting.

Many of these small industries also rely on small workers. Workshops with financial commitments (paying wages, rent and facilities) prefer to hire children to do the work. Children are paid lower wages than adults, work for longer hours, are fast learners and they do not complain or leave their job.

In a study prepared for the Red Card to Child Labour Project, by Al-Fostat Association for local community development, in the different areas of Old Cairo, over 50 per cent of the child labourers were under the age of 12. Over 60 per cent of them worked between eight and twelve hours a day and over 80 per cent worked six days a week. The randomised sample included 303 children.

Meeting a child labourer is not an easy task. Approaching them and talking to them about their work is difficult; fearing their supervisors they are reluctant to speak out. One would need to establish a rapport and hope that they talk about their work in the course of the conversation. Abdel Aal whom I met at Aboul Seoud Association for Endangered Children opened up and talked about his daily routine.

“I take the night shift at a government bakery [where subsidised bread is sold] from10pm until 10am daily and when I finish in the morning, go home to wash up and come here [the Aboul Seoud Association],” says Abdel Aal.

Abdel Aal is 15, so he is older than other kids working on the streets and in some workshops. However, he says he started working over seven years ago.

“I have been working at the bakery for over seven years now, I sort of climbed the ladder, from carrying flour to more important things now. I know the occupation really well now,” he says proudly.

Even though his father works at a coffeehouse, raising a family of seven children devours the meagre wage his father earns. Therefore, Abdel Aal’s parents make four of their boys work to sustain the household. Some work with Abdel Aal, the others aid his father at the coffeehouse. The girls go to school in the morning and work at home with their mother.

Abdel Aal is thin and scrawny his age. His face looks younger than his years, but when he talks he mimics adults. He is polite, quiet and he takes care of the young children in his class at the association.

He comes to the association to attend a class to learn reading, writing and maths because he had never been to school. He spends a couple of hours there then head back home to sleep until it is time for dinner and work again.

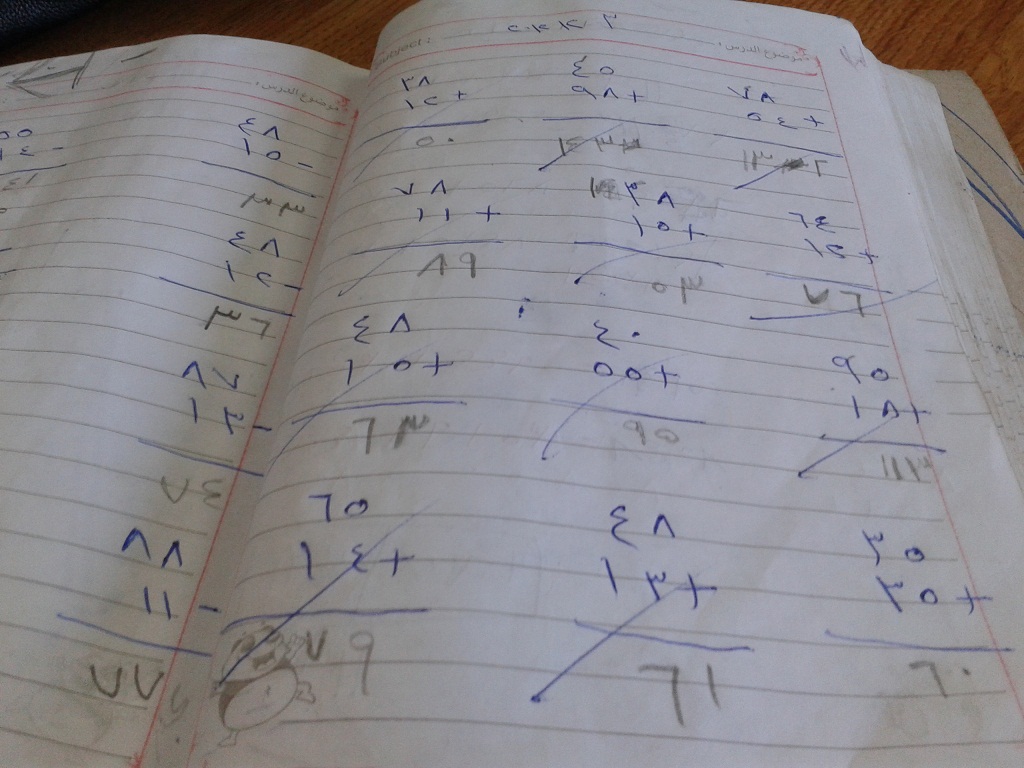

Abdel Aal likes the praise he receives for his notebook with all stars he got for copying the right word, khas, lettuce, or khrouf, sheep, or for solving a simple mathematical addition or subtraction equation. He is eager to talk about his achievements. He says enthusiastically, “yesterday I took the exam for the primary level, tell the Miss how I did Miss Yousra.” The children’s supervisor answers, “you got full marks on the maths exam and only missed one mark in Arabic.”

Returning to his job, Abdel Aal explained his laborious work at the bakery. On his own he has to carry 60 boards, each one holding17 kg of round bread dough. “Each of us has his task, no one helps me carry the boards because they have other things to do,” he says.

He adds, “it’s a hard and tiring job, but I earn 50 pounds a week, I give 35 to my father and I get 15 for myself.”

He spends the money on food and sometimes he goes to a nearby internet cafe where he has learned to type in Arabic on the keyboard to chat with friends. He beams when talking about his new discovery.

A hyperactive boy named Youssef interrupts the classroom. With messy hair and soiled trousers he approachs Abdel Aal. His grubby little hands take Abdel Aal’s bottle of coke and shake it up and down so that it froths when he opens it. Abdel Aal is unfazed by this.

Seven-year-old Youssef is Abdel Aal’s neighbour and he comes to the centre to learn reading and writing. However, from the looks of it, he is more interested in jumping around. Youssef is the exact opposite of Abdel Aal. He is much more energetic, less interested in learning. However, Youssef too works, but for no pay.

“I go to work with my mom at a building in front of Tahrir [el-Mogammaa]. I mop the stairs, she does the floors and fill up the bucket with dirty water and gives it to me to dispose of it,” he says disinterestedly. He doesn’t want to speak for long; he gets distracted fighting with his sisters and trying to steal paints for his painting.

Though different in attitudes, the two boys are both children who are supposed to be protected by the law. But they are not.

Sarah El Masry

According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO), more than 200 million children under 18 are subjected to child labour globally. The ILO defines child labour as “work that deprives children of their childhood, their potential and their dignity, and that is harmful to physical and mental development.” Any work that is morally or socially dangerous or that interferes with their schooling falls under the ILO definition of child labour. The worst forms of child labour include hazardous jobs exposing children to risks, illnesses, slavery, trafficking and separation from family.

Like other developing countries such as India and Pakistan with staggering numbers of child workers, the problem in Egypt is estimated by 2.5 to 3 million children, according to the most recent survey by the National Council for Childhood and Motherhood. However, unlike those developing countries whose constitutions and legislations prohibit child labour, Egypt’s upcoming constitution does not.

“Every child, from the moment of birth, has the right to a proper name, family care, basic nutrition, shelter, health services, and religious, emotional and cognitive development… Child labour is prohibited, before passing the age of compulsory education, in jobs that are not fit for a child’s age or that prevent the child from continuing education.” This is an excerpt of Article 70 of the constitutional draft Egyptians are currently voting on.

Human rights activists and people working on the problem of child labour have interpreted the article as allowing child labour so long as the jobs are “suitable for their age” instead of outlawing it or eliminating it. Though it protects education for children, it does not forbid combining school attendance with heavy work which is often the case for many children in Egypt.

In short, the upcoming constitution establishes child labour as a normative condition and not as an exception that should be only allowed when the other child’s rights are protected. It allows in the future that more children face the fate of Abdel Aal and Youssef.

Egypt has signed and ratified two main conventions of the ILO with regard to child labour. The first is convention 138 for minimum age for child labour. It set 15 as the legal age for employment and outlined conditions for allowing child labour. The second is convention 182 on the prohibition and immediate action for the elimination of the worst forms of child labour. Thirty seven occupations are prohibited for children to work in such as slavery, trafficking, mining, working at quarries, and other occupations. Even minors older than 15 are barred from working in these occupations.

Samar Youssef, head of the Forum for Dialogue and Partnership for Development (FDPD), a non-partisan NGO working on human rights and particularly children’s rights, explains why Egypt’s legal codes are not in favour of children.

“The ILO has recognised 15 to be the age when the child can start working. However many developing countries were able to get an exemption due to their low GDP so that technical training could start at the age of 13, provided that certain safety conditions were met and gradual contracts were offered to the child and that he or she wouldn’t work before 15,” she says.

Samar classifies child labour into the categories of domestic labour and paid labour. The former is when children work at home; the latter is when they work for money in the different sectors agricultural, industrial and in services.

She adds, “in Egypt both kinds can be hazardous because we do not have safety conditions or health care for children that comes with their jobs.”

Girls are mostly involved in domestic labour. They are left to sleep on the floors, the people hiring them overwork them and they are maltreated. Samar elaborates, “a girl labourer seven or eight years old does everything from laundry to tidying to cooking to taking care of little children younger than her. This endangers her psychological health and once she hits puberty she may be harassed sexually by the males in the house she is serving in, with no protection whatsoever.”

The situation for boys is no different. Though Abdel Aal and Youssef are both well treated in their jobs, some boys are harassed by their peers and supervisors.

Hany Helal, the secretary general for the Egyptian Coalition for Child’s Rights, stresses the need to ban violence against child workers. He says, “the constitution is silent about violence against children, trafficking and child prostitution. Most importantly, it constitutionalised child labour as a concept which is prohibited elsewhere in the world without providing guarantees.”

Children are supposed to work no more than four hours without a break and no more than six hours a day. Also, children are supposed to get more than one day off. Helal says, “in Egypt these rules are dead. The Egyptian child works more than the Egyptian adult and for a far lower wage.” Abdel Aal’s shift is for 12 hours and he gets one break only and one day off

For such breaches, the Ministry of Workforce sends its employees and monitors periodically to oversee factories in different areas.

Daily New Egypt

Helal illustrated how the heads of workshops circumvented that problem. He says, “the employees at the Ministry of Workforce get low salaries, that’s why they don’t visit all workshops they should monitor. Also, when they find out that children are working illegally at a place, the workshop owner bribes the employee from the ministry and that’s how things have worked over the years.”

Factory owners are supposed to be fined and penalised and the ministry could close down the business, but only in rare instances are these penalties put into effect.

Helal says, “again, a problem of law enforcement, but with the upcoming constitution the situation is expected to exacerbate. Article 70 is the Islamist’s Trojan horse for passing other legislation against the spirit of child rights such as early marriage.”

Samar highlights possible ways to tackle the problems. She says, “poverty, illiteracy and escaping school are all reasons for the growing problem of child labour. Violence in the education system repels children from going to school. They are violently rebuked, their opinions and questions are suppressed and they are not allowed to play because our schools have been emptied of any recreational activities.”

She insists that if violence at schools ceased, children would embrace education with arms wide open. “The state needs to establish worthwhile technical schools for children who are not interested in the conventional schooling and more interested in crafts and handy skills.

“If no one cared for those children they will deprive us from their youthful energies and spirit in the future as we’re depriving them of their childhood today,” she adds.

In a country where adults suffer to earn a living, Egypt’s children are stepped on, and stripped of their childhood to generate income for their families.

It is sad to see hardworking children like Abdel Aal and playful ones like Youssef throw their potential away and hold too many responsibilities before their time.

“I like coming here [Aboul Seoud Assocation] you know, I get to learn many things and I’m good at math. Math will also help be an engineer in the future,” says Abdel Aal.