Ethar Shalaby

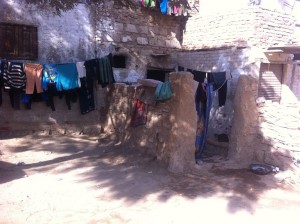

At the base of the hill known as Dowieka mountain on the outskirts of Cairo lies a shantytown called Zirzara. The small town hides a secret of widespread sexual abuse within families.

From the top of the mountain looking down you can see rows of shacks that house hundreds of families. In front of many of the impoverished homes sit girls of six and seven years, as their mothers collect garbage to make their living.

The older sister of one of these girls, Amal, 17, enters her home looking weak and shy and narrates how she was repeatedly raped by her father, ending up pregnant.

“He enters the room completely drunk…He forces me on the bed, undresses me and sexually assaults me,” she says in a trembling tone. Amal’s pale face reveals how weak she has become. She gave birth to a baby boy a few weeks ago.

Amal did not reveal that she was raped by her father until she discovered her pregnancy. Souad, Amal’s mother, says “she kept hiding [the rape] from me for almost a year. One day she came and told me she hadn’t had her period and was afraid.

“I had to send her to a family relative until she had the baby. I could not let her be seen in the area. I wanted to keep her away from everyone, especially her brother.”

Souad sent her daughter away out of fear Amal would be hurt or killed by people living in the slum, and out of shame.

*****

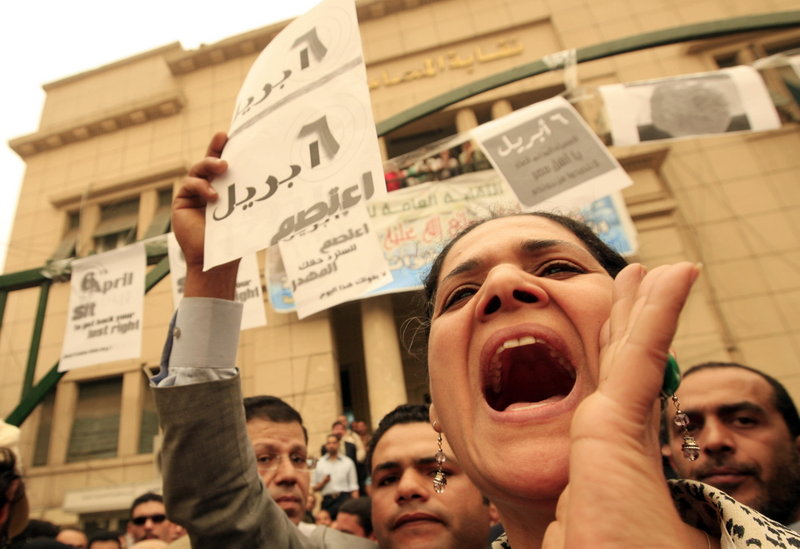

Dr Hoda Zakaria, a professor of political sociology at Zaqaziq University, outlines the extreme social stigma associated with sexual assault and why girls like Amal find it almost impossible to speak out. In patriarchal societies like Egypt, instead of punishing the abuser, victims of assault are the ones blamed.

Following most crimes, supporting and helping the victim is the usual course of action. “Rape is the only crime where the victim is held responsible,” says Zakaria.

Zakaria explains that such an attitude is prevalent among rural communities. While shooting a documentary called Virginity, the professor asked people from Upper Egypt what their reactions would be to a girl raped by 10 people. “They said that they would kill her first, then figure out what to do.”

It is all related to a value system based on shame and honour. They kill the victim to erase the perceived shame and redeem an imagined honour. Zakaria makes clear that in such a system, the value of justice and equity collapses.

Lawyer Mohamed Shawky gives an example from a Bedouin tribe in Marsa Matrouh, a Mediterranean town on the way to the Libyan border. The father was a shepherd, who left his family frequently. He was shocked to discover on his return that his daughter had been impregnated by her uncle.

“She was raped by her uncle,” says Shawky “and the man fled.” When the victim’s mother discovered the pregnancy, she told the father. “He locked his daughter up for two weeks, and did not know what to do about the shame brought upon him.”

The father believed that even if he had aborted the pregnancy, he would not be able to erase the shame. “He killed his daughter,” says Shawky, “he dug a ditch in the ground and hit her on the head.” The father then reported himself to the authorities.

Stories such as these make it clear why Souad sent her daughter Amal away to protect her.

“After I sent her away I kept searching for [her father] to tell him about the disaster. He said I don’t care. I haven’t touched her. Go see how you will deal with your shame,” Souad says.

Souad has sent away another two of her daughters, fearing that their father would one day come and rape them like their sister.

*****

Amal says her father raped her twice, although her mother believes it was more. “The first time he forced me into bed I started screaming. He threatened to kill me. I cried heavily and told him, but you are my daddy. He said that there is not such a thing as ‘father’ in situations like these,” says Amal.

Head of the psychiatry department at Damietta College of Medicine, Al-Azhar University, Mohamed Al-Mahdy puts forward a trite psychological explanation for sexually abusive behaviour. “The father is a sexually deviated person who probably has been suffering a great deal of psychological disturbances.”

Al-Mahdy suggests that people who cannot differentiate between sexually acceptable attitudes towards members of their family have not overcome their Oedipus complex, a popular psychological theory in which a boy’s perception of his mother is dominated by jealousy and anger towards his father. “When a child does not overcome this at the age of five, he grows up with a confusion of feelings towards members of his family.”

Ethar Shalaby

In Amal’s neighbourhood, another contributing factor associated with sexual abuse is widespread drug and alcohol abuse. Al-Mahdy says drugs play a significant role in familial assaults. “Those who abuse drugs, alcohol or any sort of stimulants are susceptible to any kind of abnormal behaviour,” says the psychiatrist.

Usually, Amal’s father breaks into the house either drunk or high on drugs.

Amal says her father used to touch her in a ‘strange’ way, but she never imagined he had a sexual desire. “I usually thought he is simply my father.” She says he often comes in the room apparently unaware of his behaviour and starts beating her.

“I find him entering the room beating me harshly, he will sleep with me for about 10 minutes and leave the room,” she says, adding that he has tried to sexually abuse her 10-year-old sister as well.

In cases like Amal’s, the abusive member of the family tends to grant the victim privileges over other family members, before resorting to intimidation. Al-Mahdy suggests “[the] abuser would start with bribing the victim to not tell anyone. The girl would feel that she is exceptional to her dad who treats her differently than her other sisters…The victim gets completely messed up at this stage.”

Such treatment has a profoundly damaging psychological effect on the victim. Al-Mahdy explains that the victim’s perception of her father is distorted and, in addition, she develops feelings of jealousy from her mother and sisters.

But most frequently, victims of sexual assault haunted by fear will appear “broken and silent.”

*****

Amal’s father does not have a regular job and Amal’s assaults have always occurred when her mother is busy with work, sorting through garbage to find plastic, which she sells to earn a meagre sum for a family of six children (including Amal’s brother; a drug dealer).

“I have to leave the house to bring them money. What shall I do when I hardly earn five pounds a week? This bed sheet you see here. I collected it from the garbage,” Souad says, her words broken by sobs.

Dr Zakaria believes that sexual assault in the family, when it happens, is much more common in certain areas. “Such crimes happen in Upper Egypt, some slums and rural areas,” she said, “it is usually associated with a social under class living in poverty.”

According to Zakaria, despite the lack of statistical data caused by victims’ reluctance to come forward, familial sexual assault is not a widespread phenomenon in Egypt and occurs in a very limited scope.

Al-Mahdy agrees that “poverty and illiteracy are indeed strong factors here. In slum areas, we see a family of more than four living in one room. Children see their parents during sex.”

Astonishingly, he also implies that sexually abusive fathers would be less inclined to assault their children if their daughters dressed conservatively at home.

Attitudes such as these, which seek to place any amount of responsibility on the abused, are condemned in the strongest terms by Zakaria. A girl should feel comfortable wearing whatever she likes at home in front of her father or brothers. She adds that a girl should feel safe among her family and should not be oppressed.

Sexual abuse in families usually occurs in houses where familial relations are not strictly defined since childhood and Zakaria stresses the significance of a child’s upbringing.

Restricting what the daughter can wear, or denying her rights, will not address in any way the psychological issues apparent in her father or brother.

*****

Although Amal was a victim of a great taboo she has benefitted from unusual levels of assistance from her mother. Initially they tried to abort the pregnancy. As Amal approached the end of her pregnancy in hiding, her mother would visit frequently to help her give birth quickly. “I gave her hot drinks and certain recipes to sharpen her contractions. I was the one who delivered the baby with my own hands,” says Souad

Amal hasn’t even seen her newborn baby. It was taken away immediately and her mother claims she sent it to her cousin in the Emirates. A friend of the family says that that Souad has probably sold the baby to a rich family in the gulf.

A USAID report, issued in 2007, titled Assessment on the Status of Trafficking in Persons in Egypt, highlights that Egypt is a country of origin, and not just transit, for women who are trafficked to Arab countries such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Jordan, Kuwait, and Yemen.

Amal is left more than confused. “I don’t know what to do. I now have a baby who is both my son and my brother. I didn’t even see him or know where they took him. My breast pains me. I could not even breastfeed him.”

*****

Souad is deeply troubled by events in the town. “My daughter is not the only girl who has been raped by her father here in Zirzara.” Soaud has helped three girls to abort their pregnancies. She denies earning any money in return.

There are no recent figures regarding sexual assault within the family in Egypt. “Even if there were any statistics or numbers,” Zakaria says, “it would only be the tip of the iceberg.”

Ethar Shalaby

Faten Fawzy, lawyer at the Egyptian Centre for Women’s Rights, says the main reason behind the lack of reports is that victims of assault fear reporting the crime. “There were a few cases received at the centre… but they did not reach court.” They did not reach court, because the victims refused to file a lawsuit against the perpetrator.

Fawzy believes that women fear reporting rape, especially if the person responsible is a family member. Victims complained to the ECWR mainly by telephone, but they feared taking the complaint further.

Victims do not only fear being harmed by their abuser, they also fear how society will perceive them and they do not want to be disgraced. So families seek to solve the issue in private, rather than seeking external help. These attitudes prevent specialists from acquiring precise data and offering relevant help or support.

Noura Ibrahim, responsible for a programme against domestic violence at the Centre for Egyptian Women’s Legal Affairs, says in Upper Egypt, women are usually scared to talk about their experiences with their in-laws, fearing that they would be kicked out of their house or blamed for any wrongdoings.

Ibrahim explains, “if a wife were to make a complaint of harassment against her father-in-law or brother-in-law, he would probably start claiming that she is a troublemaker, causing her problems with her mother-in-law and husband.” In most cases in Upper Egypt, where wives live with their husbands in large family homes, women and girls are more prone to sexual abuse within the family when the husband is absent.

In spite of a lack of data on the subject, Al-Mahdy believes that 75 per cent of perpetrators refrain from repeating sexual assault, when the victim informs someone about it. Though it is not a widespread issue, familial sexual assault occurs in complicated circumstances. Zakaria thinks that such cases are connected to the degeneration of morals in the victim’s family. She added that it is important to promote educational programmes and conduct awareness campaigns that address morals and enhance family structures.

Rehabilitation is an absolute necessity for victims of sexual assault. But rehabilitation is rarely provided due to fear of disgrace, and specialists say that families tend to veil the disgrace instead.

Girls in Amal’s situation usually get married quickly following the rape. Souad will help her daughter follow the example of the other three girls in the neighbourhood, who were also sexually assaulted by their fathers and/or brothers.

“I will get her married to my cousin next month. I will slaughter a chicken, and use its blood as a sign of her virginity on the wedding night,” says the mother.

*****

Social stigma frames the victim of sex crimes as the accused party. However, justice is attainable through the law in the very rare cases when the victim comes forward. Egyptian laws specifically and distinctly address sexual assault, rape and sexual abuse (hatk al aerd). The law permits severe punishment of a perpetrator who is related to the victim; is responsible for bringing up the victim; has guardianship over the victim; or works in the victim’s home.

Counselor Tamer Kamel, Head of the Appeals Court clarified that “the punishment in some rape cases could include execution.”

“I hope [President] Mohamed Morsy will order the death penalty of every father who rapes his daughter,” says Souad.

Names have been changed to protect privacy