By Darja Tjioe

The Red Sea is considered one of the best places in the world to go diving, due to the large coral reefs and variety of colourful fish. But the Red Sea offers more than sealife; diving enthusiasts from all over the world come to dive on the famous wrecks of the Red Sea.

Many wreck divers spent their childhood reading books filled with adventures in faraway places and dreaming of being part of that excitement. I was no different and among the many comic books I devoured on rainy afternoons, there is one Tintin I remember particularly well: Red Rackham’s Treasure. There was a lot going on in this story but mainly there was diving, shipwrecks, treasure hunting and a sub-marine in the shape of a shark.

The very first time I was under water and saw a massive dark blue silhouette slowly taking form in front of me, for an instant I remembered those rainy afternoons and realised a dream had just come true.

The Red Sea is literally littered with shipwrecks. The combination of it being a major shipping route between Europe, Africa and the East and the numerous reefs along the way make it a dangerous sea to travel. Given that these days even fully equipped cruise ships have trouble avoiding islands, it is easy to imagine that with less sophisticated navigation tools accidents happened regularly in the distant and not so distant past on hidden reefs.

The waters of the Red Sea truly are treacherous; sailing out of the Gulf of Aqaba into the Strait of Tiran, a cluster of reefs is waiting right there for the unsuspecting captain and many ships have run aground right there. Coming from Suez is not much different; the huge reef of Abu Nahas lies right in the middle of the route towards the south. Many of the reefs in the Red Sea are up to a metre below the surface, and especially when the weather is quiet and the sea is calm it is next to impossible to see the coral, until it is too late.

The Carnatic

RedSea Images

From the coastal towns of Hurghada and El Gouna daily diving trips are organised to Sha’ab Abu Nahas, referred to in dive briefings as the reef of copper (nahas) or bad luck (nahs), since the Arabic words so phonetically similar. Both translations work well and add to the mystery surrounding wreck diving. Five wrecks are known to lie at Abu Nahas, although there is speculation that there are many more. Maybe even up to nine shipwrecks in total, although only four are well known and accessible to all levels of divers. The four wrecks that are visited most are the Carnatic, the Ghiannis D, the “lentil wreck” and the “tile wreck”. The last two wrecks go by these cryptic names, as there is still some discussion about the correct identity of the ships.

The wrecks are positioned in a neat row on the northern side of the reef, almost as if someone laid them out on purpose to give easy access for divers. And it does not stop there, the depth range in which the wrecks lie, between three and 30 metres, is ideal for all levels of divers. Only the weather can possibly ruin the trip, when high waves make entering and exiting the water difficult and sometimes even dangerous; but some diving centres circumvent this by anchoring behind the reef and using a zodiac to drop the divers on the wrecks.

The Carnatic is the oldest wreck on the reef of Abu Nahas. It was a mixed-propulsion, two-mast steam ship, carrying passengers as well as a cargo of whiskey and soda, and a huge amount of gold. It ran aground on 13 September 1869, most probably due to a navigational error. On the captain’s order the passengers and crew stayed onboard for a day and a night, waiting for rescue, but instead the ship broke in half and slid off the reef, taking 31 people with her. The remaining crew and passengers made it to nearby Shadwan Island and were rescued from there.

The ship now lies on the seabed next to the reef at a maximum depth of 28 metres. A week after the ship sank, one of the first recorded salvaging operations was performed by hard-helmet divers to recover the gold. Even though a few divers hope they may have missed some of it, it looks like they got it all. Today, only the steel carcass and some empty, broken soda bottles remain.

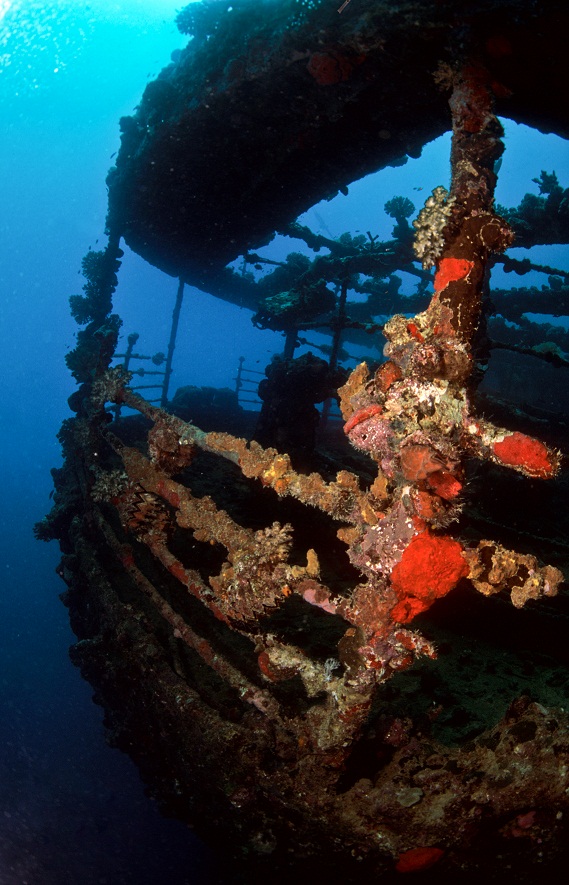

After spending more than a century under water, the ship is encrusted with hard and soft corals and teeming with all sorts of marine life. Not only is this wreck beautiful, it gives a sense of going back in time, like looking through a window into another era. The soft corals growing all over the wreck and the shafts of sunlight through the portholes create a mystical lightshow and make the Carnatic one of the most photogenic wrecks in the area.

The Thistlegorm

RedSea Images

A little further to the north, close to Sha’ab Ali in the Strait of Gobal, lies the Thistlegorm. This ship is truly the stuff of history. It was a British supply ship for the army during the second world war and was sunk by the German air force on 6 October 1941. It is now lying upright at a depth of 30 metres. Most of the cargo is still untouched and during a dive you can see Bedford trucks, BSA motorcycles, Bren guns and ammunition, Wellington boots and two locomotives.

The world was introduced to this wreck in the documentary The Silent World by Jacques Cousteau, in which he tells the story of how he discovered the wreck in 1953 and shows him diving on the wreck for the very first time and securing the ship’s bell. After the discovery by Cousteau the precise location of the Thistlegorm was lost, and people only really started diving it again in the early 1990s, with the arrival of the first diving tourists to Sharm El Sheikh.

The Thistlegorm is definitely the most famous wreck dive in Egypt, and it is way up there on the list of ‘must-dives’ in the rest of the world. The size of the ship, together with the cargo, the accessibility and the marine life make for a spectacular couple trip, and it should be on every wreck aficionado’s bucket list.

Unfortunately it is also a wreck on which you can really see the damage that is done by divers. One problem is people taking souvenirs with them, dramatically reducing one of the wreck’s major points of interest: the cargo. A second problem is bad mooring practices. Some days up to 20 or 30 dive boats are tied off on the wreck, some of them tie their lines onto very breakable parts of the ship, which leads to the slow destruction of the integrity of the wreck.

It remains a great dive despite of this, and even dive guides that work in the Red Sea are captured by the magic of it. Each one of them has a story or a tall tale about their experiences on Thistlegorm; the first time they saw it, the first time they tied a rope off, the time they lost a diver (and found him again) or the time the current was sooooo strong. We all have a story, really! Try finding out the Thistlegorm story of your guide next time you spend some time on a dive boat and even if they are a little further from the truth than they should be, they most probably are very entertaining.

The Rosalie Moller

Also known as the sister ship of the Thistlegorm, the Rosalie Moller was sunk only two days later, on 8 October 1941. Once again a German aircraft bombed the ship and it sank almost instantly, leaving it standing upright on a muddy seabed between the islands of Gobal and Queisum. With surprisingly little damage from the explosion, it is possible to see the ship in its entirety.

Also known as the sister ship of the Thistlegorm, the Rosalie Moller was sunk only two days later, on 8 October 1941. Once again a German aircraft bombed the ship and it sank almost instantly, leaving it standing upright on a muddy seabed between the islands of Gobal and Queisum. With surprisingly little damage from the explosion, it is possible to see the ship in its entirety.

This dive is a little different than the Thistlegorm. First of the all the silty bottom in this area causes poorer visibility than usual in the Red Sea. The wreck lies a little deeper as well, with the stern at around 43 metres and the bow at 46 metres. The depth combined with the reduced visibility gives the dive the sense of gloom and doom that really works well for wreck diving.

For most of the year, the ship is covered in a thick blanket of glassfish, which are hunted by about 40 of probably the biggest lionfish known to man and a school of baby barracuda. In the darker corners of the wreck, massive potato cods are lurking and waiting for the exact right moment to scare the living daylights out of you, by suddenly appearing and disappearing in the gloom. On your way up from the dive, you may find yourself in the company of some overly friendly batfish.

The Numedia

Now we make a big jump, over the islands of Gobal and Shadwan and continue south for a little while before suddenly almost bumping into two little islands in the middle of the sea. This is pretty much what happened to the Numedia. On 19 July 1901, just before dawn, she ran aground on the north point of Big Brother.

To give an idea of the skill needed to complete this feat of navigation; the northern point of Big Brother is about 20 metres wide and there is a whole lot of empty sea all around. There was a much bigger chance of missing than hitting the reef but lucky for us the captain managed to, because the Numedia is a breathtaking wreck.

It lies on the steep reef slope, starting at around 10 metres going all the way down to 80 metres. The side of the island where the Numedia lies is exposed to strong currents, which means that care should be taken when diving. It also means that there is prolific growth of colourful soft corals and an enormous variety of marine life. Around the wreck, there are good chances to see grey reef sharks, napoleons, groupers, thresher sharks and even hammerheads.

The Salem Express

RedSea Images

All the wrecks described so far have sunk with a minimal loss of life, and although every life lost at sea is one too many and should be mourned, things change when the loss of life becomes considerable, as is the case with the Salem Express.

On the night of 17 December 1991 the Salem Express was on her way back from Jeddah. On board were many pilgrims coming back from the Haj but exactly how many passengers and vehicles were on board that night is not really clear. There are many rumours that the ship was overloaded and that there were a lot more people onboard than registered.

The weather was bad and in the dark, at an hour’s distance from Safaga, where the ferry was heading, the Salem hit a reef. The collision tore open the hull and forced the bow door open, with catastrophic results. According to accounts it took less than 10 minutes for the ship to capsize and sink. There was no time to deploy the rescue boats and many people died that night.

Diving the Salem Express is not like diving any of the other wrecks. The tragedy that came to pass here is so present, so obvious, that you would have to be made of steel not to feel it. The suitcases strewn around the wreck are a painful reminder of the fate of their owners. Swimming through the restaurant, you can almost see them sitting there and hear their voices. In itself it is a beautiful dive, the wreck is practically intact and marine life is slowly starting to move into a new habitat.

There is some controversy concerning diving this wreck. Rumours were going around that people dived the wreck mere days after its sinking, to pillage the gold that people took with them on their pilgrimage. Another rumour said the gold that was obtained this way was cursed and apparently businesses that were financed with the recovered gold all came to an untimely end. The choice whether or not it is appropriate to dive this wreck is a choice that each diver should make for himself. And if we choose to dive it, I think we need to show respect towards the tragedy, the ship and the last passengers.

Saving the wrecks

Shipwrecks are graves, they are museums, they are archaeological sites; they are so much more than just heaps of old rusty steel. Even if it is not actual gold coins in wooden pirate chests, the Red Sea wrecks are a treasure. And treasures are not to be thrown away or handled carelessly.

In 2006, HEPCA (the Hurghada Environment and Protection and Conservation Agency) launched a project called Saving the Red Sea Wrecks designed to save what is left of the most famous wrecks by decreasing damage done by destructive mooring practices and air pockets left by divers.

Many meetings were held, dive centres consulted, money was raised and sites were closed for maintenance. Around the Thistlegorm 32 moorings were installed to provide alternative attachment points for dive boats. Several strategically drilled holes were added to get rid of air pockets otherwise adding to the natural corrosion on a wreck.

It helped, a little, if only for the awareness it created among divers. Both professionals working in the Red Sea and the many visitors started to realise that what we have today, will not necessarily last until tomorrow, and there are a few things we can do to preserve this accidental heritage.

If you are a wreck diving aficionado here is what you can do to preserve the past:

Refrain from dismantling wrecks (obviously dismantling and preservation are not compatible).

Take nothing. Even the bits that are not attached to the wreck, leave them where they are. That very cool Wellington boot that you took with you is now a pile of crumbled rubber in your garage, while on the Thistlegorm many divers could have enjoyed it.

If you absolutely have to tie onto a wreck use a rope, steel wire cuts through already corroding steel.

If you absolutely have to tie onto a wreck, avoid tying on to wobbly masts, anti-aircraft guns and the likes… surprisingly, they come off!

Most of all though, come to the Red Sea. Come and see these famous sites with your own eyes. Come and let your inner child experience the adventure that it has been dreaming of. Come and get your Thistlegorm dive stamped and signed off in your logbook. Do not take my word for it, come and see for yourself.