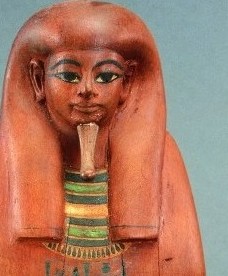

( Photo courtesy of Stop the heritage drain Facebook page)

Antiquity smuggling has witnessed an unprecedented surge in the two years since the 25 January Revolution since it is an easy way to make immediate money, even if it is on the account of Egypt’s heritage and history.

The fragile security situation in the country and the financial and economic ordeals the population is suffering from are considered the main reasons behind this phenomenon. Given that a small, wooden, carved Pharaonic statue or a marble bust can be sold for a large sum of US dollars, there are many who take advantage of this immediate influx of cash that can immediately improve their standard of living.

Consequently many historic antiquities are found missing from museums throughout Egypt and sealed historic areas are subjected to random excavations carried out by inhabitants looking for any hidden or unknown antiquities.

The Egyptian Council for Culture and Arts mentioned in its report last year that the amount of stolen Egyptian antiquities reached about 3,000 artefacts, probably now residing outside Egypt in the hands of private collectors.

The Ministry of Interior and the security forces have proven to be incapable to stand against and stop this heritage drain in Egypt and the Ministry of Antiquities refuses to publicise which parts of Egypt’s heritage are missing.

This situation provoked a few young Egyptians to start a public effort to try to stop this loss of historical artefacts by launching the independent “Stop the heritage drain” movement, which posts and publicises photos of the missing pieces on the internet on their Facebook page. “The Ministry of Antiquities must declare the theft of antiquities to stop the smugglers from being able to market the stolen pieces internationally,” Yasmin El-Dorghamy, movement cofounder, said.

It is vital to document all antiquities to make their repatriation process easier; however, still many newly discovered pieces are left undocumented by the ministry. The movement aims to document the stolen pieces and it asks foreigners to send in photos of any antiquities which might be offered to them or have found their way into their collections, in an attempt to thwart the illegal antiquity market.

The Facebook page contains multiple photos of missing and smuggled antiquities, like a small wooden Pharaonic piece called Shabtis with its registry number, date of when it went missing and original attribution granted by the administration of the Egyptian Museum. “The Egyptian Museum recently started to cooperate with us by sending us photos of the objects that went missing or were stolen during the Egyptian revolution, unlike other museums and parties, including the Ministry of Antiquities,” El-Dorghamy said.

The page also includes the images of copper- and silver- engraved panels, door-knockers and other objects that have been removed from the Al-Mo’ayad Sheikh, Sultan Hassan and Sultan Barqouk mosques located on Al-Mo’ez Avenue, in addition to historic books, stamps and paintings. “This is a high-profile theft operation. These exquisitely engraved antiquities were admired by visitors and photographers for years but now they are missing,” El-Dorghamy said.

Egypt is one of the wealthiest countries in the world when it comes to the enormous amounts of monuments and antiquities that have been preserved from the past, but the mismanagement and inadequate protection of this heritage by the political and executive administrations will lead to an irreversible loss of these historical treasures. Initiatives like these will hopefully help to stop this from happening.