(Photo Courtesy of Google)

Google has launched a new service allowing users to make an “online will” specifying how they would like their data to be managed in case of their death.

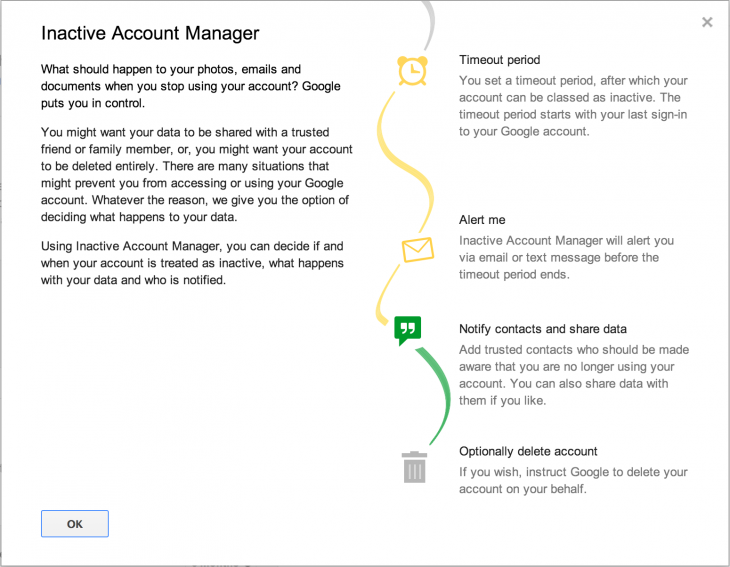

The new service, officially called the Inactive Account Manager, but popularly referred to on online blogs and social networks as “Google Death”, will allow users to choose whether to delete their data entirely or to make it available to a trusted friend or family member, once their account has become inactive for three, six, or 12 months.

The service will be applied to all Google products such as Gmail, YouTube, and Google search histories.

“Not many of us like thinking about death, especially our own,” said Andreas Tuerk, Google’s Product Manager, on Google’s Public Policy Blog.

He continued: “But making plans for what happens after you’re gone is really important for the people you leave behind. So today, we’re launching a new feature that makes it easy to tell Google what you want done with your digital assets when you die or can no longer use your account.”

The feature has now been added to the settings page for Google accounts.

“We hope that this new feature will enable you to plan your digital afterlife in a way that protects your privacy and security and make life easier for your loved ones after you’re gone”.

Tuerk emphasised that before systems take any action, Google will first warn their customers by sending a text message to their cell phone and an email to the secondary address which the user has provided.

“Your Google assets could be 1s, Blogger, Contacts and Circles, Drive, Gmail, Google+ Profiles, Pages and Streams, Picasa Web Albums, Google Voice and YouTube,” Tuerk continued.

The concept of a digital afterlife is not recent. Nine years ago, the family of Lance Corporal Justin Ellsworth, a US Marine killed in Iraq, battled with Yahoo for access to his email account. The family went to court over the matter, and in April 2005 a judge signed an order to Yahoo to provide the contents of Ellsworth’s email account.

In the same year the MySpace website launched MyDeathSpace, a website that highlighted the accounts of members who had passed away.

In 2009, Facebook provided more details on the process for memorialising the profiles of members who had died, allowing family members to create a memorial page for their loved ones.

The company said that deceased members will not appear in the suggestions box and that only their Facebook friends can see that person’s profile or find them via search.

“I think it’s a good idea,” said Ahmed Mahmoud, an architect, “but Google might strengthen it with a new feature by sending Qur’an [verses] or Dua’s [supplications] to my account, enabling my trusted friends to upload these or send them.”

Menna Mohamed, a student at the Faculty of Mass Communication at Cairo University, was positive about the feature. “It’s a good idea,” she said. “I really want my account to be closed after my death.”

Mustafa Abu Zeid, however, another student at the same faculty, described it as a “Google April Fool’s Joke”.

“I feel it’s a ridiculous application, and I don’t like it,” said Mohamed Fathy, a journalist at Al-Masry Al-Youm newspaper.

Ibrahim Mosa’ad, a security researcher at online security group Vulnerability Lab, said that the service will “help in recycling accounts in case some people create different accounts for impersonating others, for example, and then forget about that account”.

He added: “I like that it simulates your real life, as you have a normal life and you have a digital life, where just like in the normal one, you are either alive or dead.”