The protests that toppled governments were fueled by anger over the lack of a basic element in market economies

Al Qaeda is resurgent in Mali, Algeria and beyond. Violent turmoil and anti-Western hostility are rising in the Middle East and North Africa. Two years after the Arab Spring, it would be easy to become discouraged about what the mass awakening has wrought.

That would be a mistake. Unfortunately for al Qaeda and its allies, much more promising forces are at work, sending positive signals for the West, if only the West will listen.

Research in the region conducted by my organization, the Peruvian-based Institute for Liberty and Democracy, has found strong evidence that the Arab Spring revolution was rooted in a desire for what in the West would be called a market-based economy. Arabs and others may not always use that phrase, but their desire for the economic security that comes with property rights and other rights is a force that the foes of individual freedom will not easily overcome. The challenge is to harness that force by offering people of the region the legal protections and security that are the bedrock of all successful economies.

Recall the catalyst of what became the Arab Spring: the self-immolation in January 2011 of Mohamed Bouazizi, a Tunisian fruit vendor protesting the expropriation of his merchandise. According to our estimates, more than 200 million people throughout the Middle East and North Africa depend on income from operating businesses or occupying property in the informal economy, without the protection of the rule of law.

That means the entrepreneurs who want a legal system with property rights like those in the West outnumber al Qaeda membership in the region, often estimated at up to 4,000 core activists, by a ratio of about 50,000 to one.

Some other research highlights:

Mohamed Bouazizi’s desperate protest wasn’t unique. We found that at least 63 more men and women in Tunisia and also in Algeria, Egypt, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, Syria and Yemen, who followed Bouazizi’s example within 60 days of his death. That was the critical period during which governments were toppled or dramatically shaken. Forty percent of these protesters survived, and some of them are contributing to our research on the difficulty of living in societies without property rights or other freedoms.

All 64 of the self-immolation protesters were engaged in extralegal businesses, and they made their dramatic statements for economic rather than political or other reasons. In filmed footage of real-estate owner Fadoua Laroui in Morocco, for instance, she declares that she is protesting “economic exclusion” just before setting herself on fire in front of a municipal building on 23 February 2011. In an on-camera interview, Mohamed Bouazizi’s brother, Salem, told me that Mohamed set himself alight because he believed that “the poor also have the right to buy and sell.”

The principal reason that self-immolators gave for their acts was “expropriation”, governmental seizure of property. A common view of Bouazizi’s death is that he killed himself because a policewoman slapped him and robbed him of his dignity. No slap in the face drives five dozen people to try to burn themselves to death. Every survivor without exception has told us it was about desperation over property.

We calculated the value of Bouazizi’s confiscated assets to be $225. Yet when legal property rights don’t exist, the damage goes far beyond money. Because Bouazizi wasn’t protected by law, his ability to conduct business depended not on an enforceable right but on the goodwill of local authorities. Once these authorities withdrew their protection and seized his goods, Bouazizi was ruined. There was no legal system in place by which he could hope to recover from bankruptcy.

Under contract with the Egyptian government, and with funding from the U.S. Agency for International Development, my institute undertook a five-year study that involved 113 Egyptian professionals working with us to ascertain the size of the gap between recorded property, including factories, cars and land, and the actual amount of property in those and other sectors. We found that 82% of businesses and 92% of land holdings were unrecorded and thus unprotected by the rule of law.

We refer to this enormous area of human endeavour as “extralegal” assets and transactions, meaning that the people involved don’t have access to a legal system that codifies and protects the rights between owners; provides standard rules and records that allow comparisons; measurement and pricing; and enforces contracts or creates the guarantees and precise information needed to generate credit and capital. Such activities make up a shockingly large proportion of the economies of the region.

In Tunisia alone, 85% of enterprises, with an estimated value of $22 billion, are extralegal. The value of extralegal real estate is estimated at an additional $93 billion. This combined figure of $115 billion represents 11 times Tunisia’s total stock-market capitalization in 2010 and four times the amount of foreign direct investment in Tunisia since 1976. If the Tunisian extralegal economy were an American state, its gross domestic product would surpass the individual GDP of 17 other states.

We have estimated the value of Egypt’s extralegal economy at $350 billion, six times greater than the value of all foreign direct investment in Egypt since Napoleon’s forces departed in 1801. That is a startling reminder that no amount of money Western nations or investors transfer to these countries can ever come close to the economic potential locked up in the entrepreneurial aspirations of their people.

The Institute for Liberty and Democracy has published and debated these findings on television, radio and in university conferences in the North African countries now weathering “revolutionary fluidity,” as the post-Arab Spring unrest has been called. The interest we encounter, from local media and across the political spectrum, has been intense. And there are signs of progress. With the support of the Tunisian government, for instance, we have associated with Utica, an organization representing 300,000 legal entrepreneurs, with the goal of nurturing property rights. Popular anger is unlikely to abate until the majority of Tunisians see serious reform that protects the fruits of their labours.

Does the West get it? The opportunity cost of misinterpreting the causes behind the continuing instability is huge. The US and its allies risk missing a chance to overhaul a system that creates the poverty and anger on which the likes of al Qaeda thrive. If the West focuses its aid and advice on efforts to establish legal protections for property rights and private business, it will find an avid audience, and new admirers, in the millions.

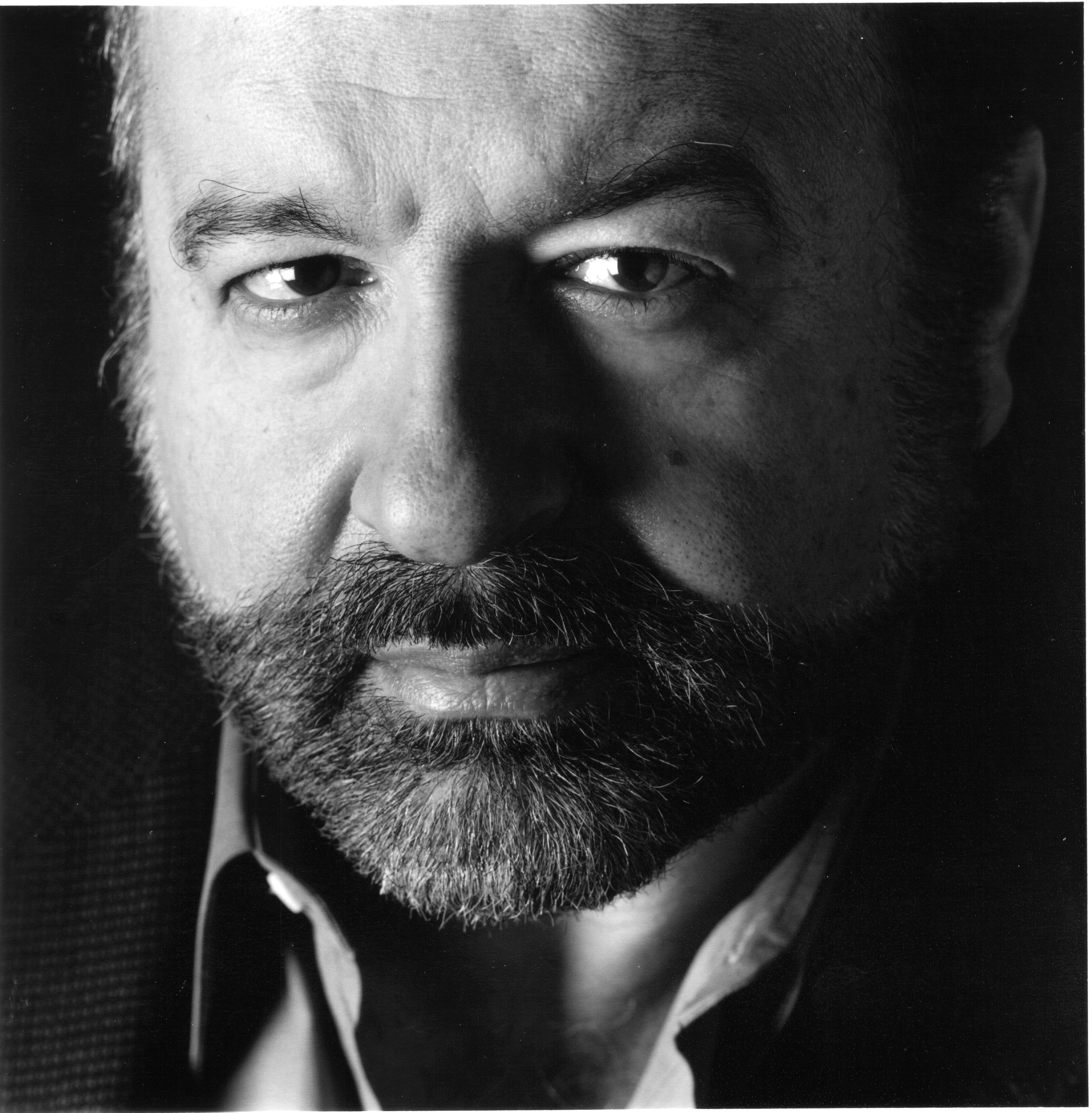

Mr. de Soto, the author of “The Other Path: The Economic Answer to Terrorism” and “The Mystery of Capital,” is chairman of the Peru-based Institute for Liberty and Democracy.

Article was originally published in The Wall Street Journal