By Ailie Conor

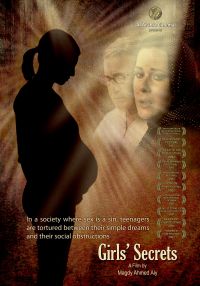

Asrar El-Banat, or Girls’ Secrets, is described as a film about “a 16-year-old girl from a decent middle class family that discovers her own sexuality in a community where there is no place for open dialogue”. Released in 2000, it at first seemed a strange choice for the Netherlands-Flemish Institute’s film screening, but the first scene underscored perfectly why this is a timelessly relevant piece of Egyptian cinema.

The film opens as 16-year-old Yasmeen secretly gives birth to a baby in her aunt and uncle’s bathroom. She and the baby are then rushed to hospital, where she undergoes surgery during which the surgeon, without the permission of either Yasmeen or her family, circumcises the unconscious girl. This shocking introduction paints a gloomy and confronting picture of the general approach to sexuality in Egypt, particularly for girls.

Throughout the film we see Yasmeen attempting to kill herself as her parents struggle to come to terms with the shameful birth, blaming her and then themselves, while her liberal aunt tries to support her. Intermittently, we see flashbacks of her conservative and sheltered upbringing and her biology class on reproduction which the teacher decides not to teach after students react to the subject matter with a mix of prudishness and insolence.

We see her friendship and shy relationship with her neighbour Shady, and him coercing his way into her room while her parents are away. He kisses her despite her protests and the encounter eventually leads to the baby’s conception.

When the film first came out it shocked most viewers. Director Magdy Ahmed Aly said that most conservative audience members were shocked by the number of taboo topics the film covers so candidly. Worryingly, some saw the film as ‘an excellent warning’ to young girls, completely missing the message of the film.

The director underscored the importance of the shock value of the film, which forces people to face the consequences of sweeping young people’s emerging sexuality under the rug. The helplessness of the young protagonists and their complete lack of knowledge combined with the shame and fear of their families is a comment on the harm caused by cloistered upbringings without any dialogue or room for exploration.

The film also highlights the role of stigma in Egyptian society; at first Yasmeen’s father’s biggest fear is the judgment of neighbours, and at one point he stands by the baby’s incubator considering cutting off the oxygen flow.

While these were all prevalent problems in 2000, the director argues that although the message is still extremely relevant, it is not as potent today. Not because society has changed dramatically, but because the youth have. In Asrar El-Banat the young characters seem lost and helpless and entirely at the whim of their older relatives throughout the film.

However, Magdy said, perhaps if he made the film today the characters would seem less like victims. They might be braver because since the revolution Egypt’s youth have become more confident in expressing themselves.

He highlighted how young people have carved out a space for themselves in the last few years. “During the revolution we [elders] were surprised by the youth because usually we do not see them,” he said, arguing that a similar film produced today would certainly reflect this. While the director was optimistic about young people in Egypt tackling these issues and the fact that the situation has improved somewhat, he emphasised that the current regime is trying to turn back the clock, restricting sexual education and censoring film and television production.

Magdy stated: “I am not going to surrender to what is happening… this is a battle.” This is why Asrar El-Banat is still extremely relevant and why people need to keep making these kinds of films. It sends a clear message that it is important that young people, particularly young women, continue to fight for their freedom and challenge society’s expectations.