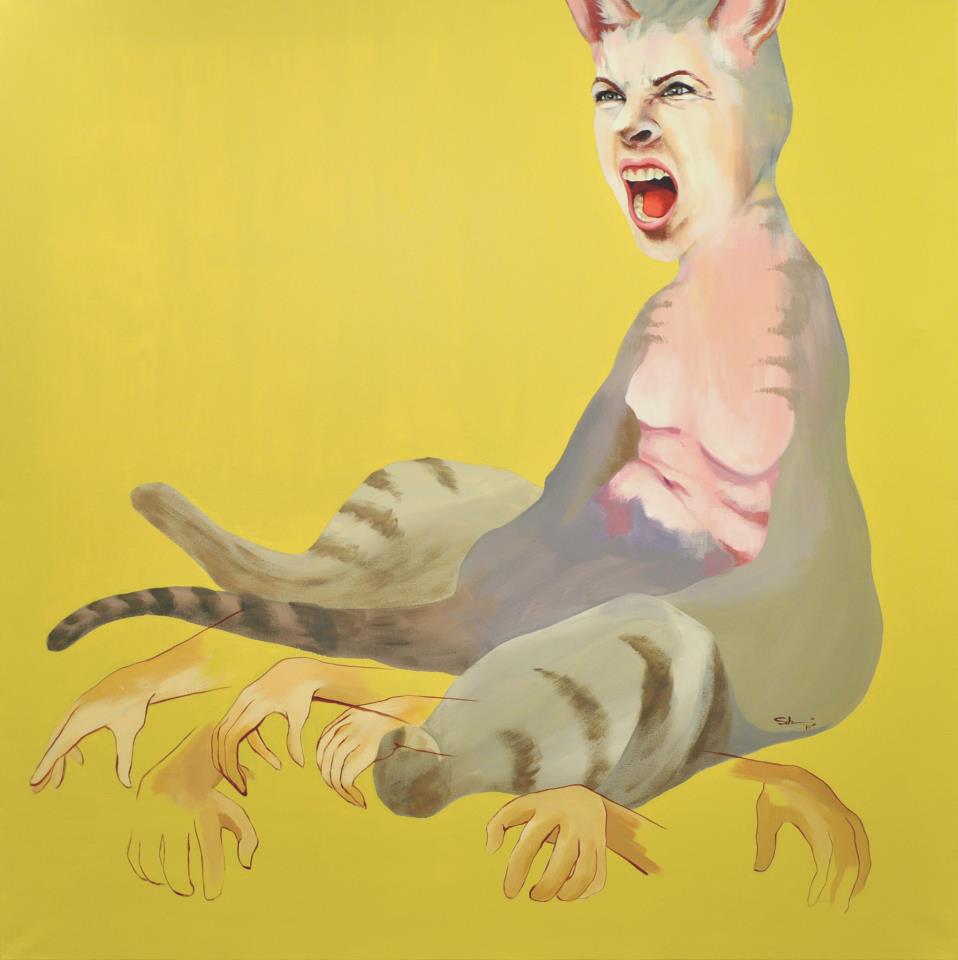

(Photo from Gallery Misr Facebook)

Currently Gallery Misr is filled with creatures, which were given life by artist Shaimaa Sobhy. The creatures, which at times are frightening, were inspired by centaurs, or rather female centaurs. The centaur is a half-human, half-horse mythological creature, and is attributed to the myths of ancient Greece and Rome. One theory suggests that the idea for centaurs emanated from Ancient Greek communities that were not familiar with horseback riding. So, when people of those communities saw a man riding a horse, from a distance the figure appeared as if it was a half-man, half-horse creature.

The idea of female centaurs was not common in early ancient Greece, probably due to the culture’s patriarchy. In ancient Greece, especially Athens, women had a very limited role in society and their life mostly revolved around the domestic aspect. There were exceptions like the Spartans, where women were free to go outside and practice sports, but the Spartan society was often labeled by Athenians as a loose society. Athenians often cautioned women against their Spartan counterparts.

Artist Shaimaa Sobhy chose to only focus on female human-animal hybrids. The gallery had the collection critiqued by art critic Dr Yasser Mongui. He points out that when female hybrids (not as centaurs) appeared in ancient Greek and Roman cultures, they were negatively portrayed. “Greco-Roman and Babylonian mythologies produced nymphs such as the nocturnal Lilith, a female demon who was thought to be responsible for spreading panic and diseases; and provoking seduction and black magic,” Mongui explained.

He contrasts the ancient treatment of female hybrids to the modern understanding of human superheroes: “The contemporary American culture sought animal-human hybrids to create symbolic super-heroes who could overpower evil forces, which threaten mankind in modern times.”

He then comments on Sobhy’s take on female identity. “Since she initiated her artistic career, Sobhy has been overwhelmed by her gender identity; she upgraded the idea of metamorphoses to free her creatures from the fetters of grotesque forms. Nor did the artist limit her metamorphosed bodies to simple optical rendering,” Mongui wrote.

It appears that Sobhy did not aim for the painting to only be described as “aesthetically pleasing”, but really delved into the idea of hybrids. The rejection of the hybrid appears in the paintings, but it does not affect them. The creatures do what they please without a care in the world. The main painting, featured on the poster for the exhibition, tauntingly sticks out her tongue to the viewers. You either accept the creatures or suffer the consequences, namely cruel indifference.

“The erotic message is elaborate, not symbolic; direct, not illusive. There is a face-off between the viewer and defiant crossbreeds, which escaped condemnation for their eroticism by renouncing their human identity. Sobhy’s creatures testify to the reality of the ongoing human-animal struggle over identity,” Mongui wrote.

The paintings are definitely an acquired taste, but they have a Frida Kahlo-quality, mixed with Picasso-like proportions and Alice in Wonderland characteristic. The Cat painting reminds viewers of a female version of the nonchalant Cheshire Cat, but maybe an angrier version of it. The most “beautiful”, in the conventional sense is the Bird painting, but as the whole exhibition screams, that it not the point. You cannot help but look helplessly at the paintings and try to figure out what the creatures are trying to say.

The exhibition will continue until 23 May at Gallery Misr in Zamalek.