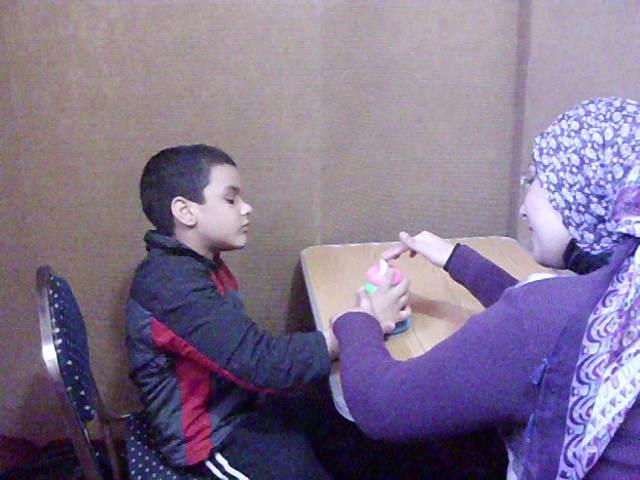

(Photo by: Ethar Shalaby)

Sanaa Mansour cannot forget the day she lost her baby. In Manshiyet Al-Bakry public hospital in the Gisr Al-Sewais neighbourhood of Cairo, the mother narrates her story. “I delivered the baby about three weeks ahead of my due date. The paediatrician said it needed to be instantly placed in an incubator, [but] there wasn’t one available,” she says. Her husband said they kept going to several hospitals but none accepted to admit their newborn. “I tried to call my manager, [thinking] maybe he could help me with his connections with people in charge, but he couldn’t help with finding a hospital with an available incubator,” he said. The 32-year-old Mansour, who works as a hairdresser, blames the government for the dilemma of incubator shortage. She believes that Egypt’s under-privileged citizens are the only ones who face this problem and cannot save their babies, because they cannot afford to have their newborns admitted in the expensive incubators of private hospitals. Indeed, an average private hospital charges from EGP 500 to 1500 a night for an available incubator.

Poverty compounded with pain

After racing against time to save their baby, Mansour and her husband failed at their attempts. Their newborn had weak lungs and could not survive more than two days outside an incubator. The mother says after going back home, she suddenly found her newborn not moving. “I was expecting the death. May God make it up to me,” she says.

In Manshiyet Al-Bakry hospital, there are about 30 incubators that cater for scores of babies born every day. Dr Sahar Sobhy, head of the neonatal unit in the hospital, says the incubators are always fully occupied and the main problem lies in the shortage of nurses and the need for extra incubators. “The incubators themselves are good, but the difficulty appears in having the suitable number of nurses to care for them. There are not enough nurses,” she said. Heba Mahmoud, a nurse in the same hospital, explains that nurses have to leave their shifts in public hospitals and go to private ones to earn more money. “I earn a total of EGP 400 every month from my job at a public hospital. This money is almost nothing. I therefore have to work here to get more money for my living,” she said. Mahmoud, who also works in Al-Nozha International Hospital (NIH), one of the well-known private hospitals in Cairo, explains that her hourly rate in the shift can reach up to EGP 9 in the private hospital.

Dr Sobhy says the problem of incubator shortages is interrelated to many other predicaments existing within the entire Egyptian medical sector. “Nobody cares to increase the nurses’ salaries and thus they had to find jobs in other private hospitals or clinics that offer them more money,” she says. Her colleague Ibtisam agrees. She says hospitals of the public sector have a lot of problems and the management cannot control the situation. “The demand on incubators is quite high and the incubators themselves are expensive. The country is poor,” she says.

Mansour says when she went along with her baby to the public hospital, the administration of the hospital claimed that there were no available incubators and advised her to go to one of the private hospitals to save her infant. She later realized that they had to be well-connected to doctors inside the hospital to facilitate the admission process of their child. “My baby died already and now I have nothing to do but to pray and hope that no mother would ever feel the heartache I felt when my newborn died,” she says.

Mansour and her husband aren’t the only victims of the incubator shortage in Egypt. A doctor in the same hospital, who declined to reveal his name, said about 10 babies die in a week due to the incubator shortage. According to the official count issued by the Ministry of Health, 2,382,000 births were recorded in 2010. The paediatrician said around 10% of the total count of births requires incubators. Hisham Shihab, a former head of the Ministry of Health, was quoted as saying in Al-Watan newspaper that the total number of incubators in public hospitals and health facilities is 3,689. Sobhy explains that hundreds of babies are denied the access of the only available 30 incubators in a typical public hospital.

Other than public hospitals, there are charity organizations that provide free incubators called “Al-Gameiat Al-Shariah”, or the Al-Sharia Society. Such health facilities belong to charity organizations, which are mainly founded on religious backgrounds.

Mohamed Al-Sayed, a father who managed to save his infant from death, said he had to take his infant to one of those charity medical centres which supplies free incubators for babies who could not be admitted in public hospitals. “I took [my baby] Fatma, to one of Al-Gameiat Al-Sharia in Nasr City and she stayed there for about 15 days. The doctors said her lungs were weak and [she] had rapid heart palpitations, thus she had to stay there for a long time,” Al-Sayed said. Luckily enough, the father found one incubator available in the charity medical centre after leaving Al-Galaa Public Hospital.

Dr Meena Aziz, a paediatrician who works at the American Hospital, says the situation in neonatal units of public hospitals is deteriorating. “Besides working here, I also have shifts in Al-Matarya governmental hospital. The problem appears in the increasing flow of parents coming from Upper Egypt with their infants to be admitted in incubators here,” he said, adding that the administration in most public hospitals do not intervene to help in solving the problem. No Ministry of Health officials agreed to comment on the subject, but many have generally commented that “it is a growing problem that needs a speedy action”.

(Photo by: Ethar Shalaby)

Nurses: Passive or needy?

Inside Al-Galaa hospital, one of Egypt’s largest public hospitals, mothers and fathers are seen sitting in the hall in front of the neonatal unit waiting for a vacant incubator to save the life of their cherished one. Om Habiba, a mother sitting with her infant on her lap, appears tearful. She says has been waiting for seven hours in front of the hall to be able to admit her newborn into a free incubator. “I don’t know what to say… we have been waiting like this since the morning and I am afraid the baby would die…he is just a small piece of red meat,” she says. Mothers’ screams fill the surrounding hallways and many quarrels are recurring between fathers and nurses.

Nurses go in and out with cold retorts to scores of restless parents. “What shall I do? There is no place, come and see for yourself,” replies one of the nurses to a crying mother. Amira, one of the nurses, asks a father in the waiting area, “Where is my present?” She probably was implying a sum of money to help the father get a free incubator for his infant. Safaa, a nurse in the hospital, explains that nurses need to make more money to be able to make a living.

“Honestly, we have to ask parents to give us money. We make nothing here,” she says. The nurse reveals that there are some hospitals in Egypt that do have enough incubators and competent neonatal units, but are closed down. “With my own hands, I have closed the neonatal unit in Al-Doaa Hospital in Heliopolis after we received instructions from the Ministry of Religious Endowments that operates the hospital. The machines are good but the problem is that there are not enough nurses to work there,” she says.

(Photo By: Ethar Shalaby)

IVFs and triplets add to incubator shortfall

Khaled M.Abbas, General Manager of Dr Yosri Gohar Hospital, one Egypt’s private hospitals, said the problem of incubators in the country is incredible. “We have a shortage of incubators in both private and public hospitals. Probably in the private hospitals the problem cannot be compared to public hospitals because the infant is charged, so whoever can afford an incubator will have access to one,” he says.

The number of babies having problems after birth is exceedingly high. At least two out of every ten babies die due to incubator shortage, Abbas says. The incubators are not adequate to cater for all newborns requiring this kind of care, in addition to the skyrocketing prices of infant medicines. “The trend these days is that we also have shortage in expensive medicines, not only incubators,” he explains. “I can tell you that some injections cost EGP 1500.” Abbas adds that good incubators are quite expensive. A typical (and not very advanced) incubator can reach up to EGP 140,000 with its provisions.

Elaborating some other causes of the incubator shortage in Egypt, Abbas says because In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) centres have vastly increased in Egypt, the demand for additional incubators is also spiking. “Women who cannot get pregnant normally undergo IVF procedures and eventually end up with delivering not less than two or three babies,” he said. These infants definitely need incubators because they are mostly born before full term.

“Pregnancies resulting from IVF procedures usually do not deliver at full term, and thus the demand for incubators is getting high. They usually deliver at 35 or 36 weeks. This inevitably means incubators. One of the babies would definitely be a premature baby,” Abbas explains. At Dr Yosri Gohar Private Hospital, there are about six incubators, but Abbas says the number of incubators in private hospitals depends on the number of rooms. “If it is a small hospital of 20 to 30 rooms, you are talking about 20 incubators, which would be fine,” he said.

Dr Ashraf Ramsis, a physician in the premature babies section in a public hospital, agrees. He says that multiple births are indeed an influencing factor in the issue. There is a major shortfall on provisions of incubators. “There is a scarcity in the number of respirators attached to the incubators. In public hospitals, there is a great difficulty getting good incubators and the other supplementary devices attached to it,” he says.

There is also a notable lack of coordination between units in public hospitals. “You can see that doctors in the maternity wards are working without any synchronization with the paediatrics and neonatal units. This lack of coordination results in severe losses, infections and a higher death rate of newborns.” Looking at the infection control in neonatal units, Dr Ramsis denounced how careless many nurses and doctors are in many public hospitals. “The number of patients is very high and the medical staff sometimes cannot keep on track with everything happening to all the cases. Many babies who do not die get out of the incubators with infections,” he says.

Perhaps every other day in Egypt, a newborn waits to see whether or not he or she has the chance to live another day. Until the government draws up serious plans to limit the severity of incubator unavailability in the country’s public hospitals, the pain felt by mothers during labour will persist until they go back home with a birth certificate for their little one.

Over the course of several months, Daily News Egypt has investigated the shortfalls of public neonatal units, and their dire effects on families. Mothers’ screams fill the air, while long lines of fathers stand waiting for a vacant government incubator to save their child’s life.