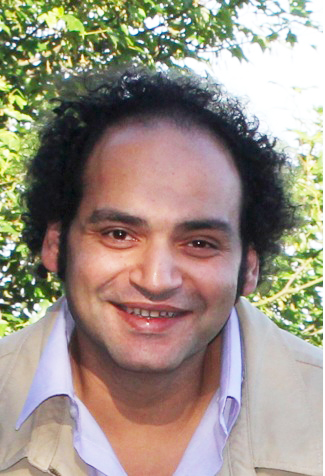

Ziad Bahaa El-Din

Al-Shorouk Newspaper

Columnist Ziad Bahaa El-Din tackles the issue of the new tax law issued by the Shura Council. “While Egyptians are busy pondering the fate of the kidnapped soldiers, the economic crisis, the blackouts, and preparing for the exams season, the Shura Council is issuing a new tax law. Its purpose is to increase proceeds and offset the huge budget deficit.”

He proceeds by acknowledging that the government’s tax increases are to be expected given the state of the economy, but blames them for their lack of transparency and careful preparation for the consequences of that law. He explains that this will only hurt the economy, the government’s credibility and decrease people’s confidence in the economic system.

He then tackles the new tax proposal concerning bank provisions.

“Bank provisions are the sums of money that a bank extracts from its returns and puts aside for possible future losses in case some of its clients are unable to pay their debts,” Bahaa El-Din explains. “The main function of commercial banks is to take money from clients wishing to save, and reroute it through investing it in other clients’ loans.” Therefore, the bank always puts money aside so that in case the loans are not paid off, the other clients, who gave their money to the bank as savings, do not suffer the consequences. He then explains that central banks around the world require commercial banks to have such provisions.

During the past 10 years, the Central Bank of Egypt followed the same policy, and that is why banks were able to escape many economic crises. He then adds that the current Central Bank of Egypt governor announced that he will continue on with the same policy. “The Egyptian law, until last week, allowed banks to consider 80% of these provisions as expenses that can be deducted from the annual tax. This is because when the bank cannot use the money, it becomes a burden and an expense that can be deducted from its taxed profits,” he explained.

The government then decided to tax these provisions, he says, without realising that banks would be paying taxes for money that might be lost in the future. In addition, the new policy might lead banks to start slacking off in setting aside provisions. However, he explains that depositors’ money is safe since the Central Bank of Egypt is still forcing banks to set aside provisions regardless of the new tax law.

Bahaa El-Din then explains that the problem is not only in the law itself, but in the way the proposal for the law was handled. This tax law concerning bank provisions was not included in the government’s proposal, but was put in at the last moment as if it was a “military secret”, Bahaa El-Din says. Secrecy in tax law proposals is only acceptable in the case of issuing taxes on certain products, where discussing the proposal in public might lead to serious problems. Yet, in the case of bank taxes, Bahaa El-Din asserts that it must be presented to the public before being discussed in parliament.

Furthermore, the law was issued without the approval of the Central Bank of Egypt, which he says goes against logic, known international procedures, and the Egyptian Banking Law. It is also not known why the tax adjustment was proposed. “It is reported that even the prime minister was unaware of it, and senior officials of the tax authority were surprised by it, which begs the question: who is governing Egypt?” Bahaa El-Din writes.

Even more shocking is that neither the consequences of this tax law, nor the expected proceeds were thoroughly discussed, and experts are conflicted regarding the projected earnings, and whether it will be enough. “Will it benefit the economy or harm the banking system? Is it one of the requirements of the IMF (International Monetary Fund) deal? Was the effect of the law on future provisions discussed?” he asks, saying that all these questions were not discussed in the law’s proposal. He adds that this is the same manner with which the tax on stock market transactions was handled, and that the proceeds from that law were not worth the confusion it caused.

He explains that if that was one mistake concerning one law, it would have been correctable, but that “we are facing a continuous case of taxes and financial confusion, which started since the president issued a bunch of tax laws last December. Then, the presidential spokesman came out at 3am to announce that these laws were ‘frozen’. This was a precedent in the history of Egyptian tax law since no one knows of anything called ‘freezing’ taxes,” Bahaa El-Din writes.

He concludes that there is an attempt to garner any amount of money possible, from any source, even if it comes at the expense of economic stability. In addition, he notes a complete disregard for the opinions of experts, and the state of the economy’s reputation. He asks whether there is a sane person who can admit that the law was a mistake or “does the ruler’s dignity forbid such action?”