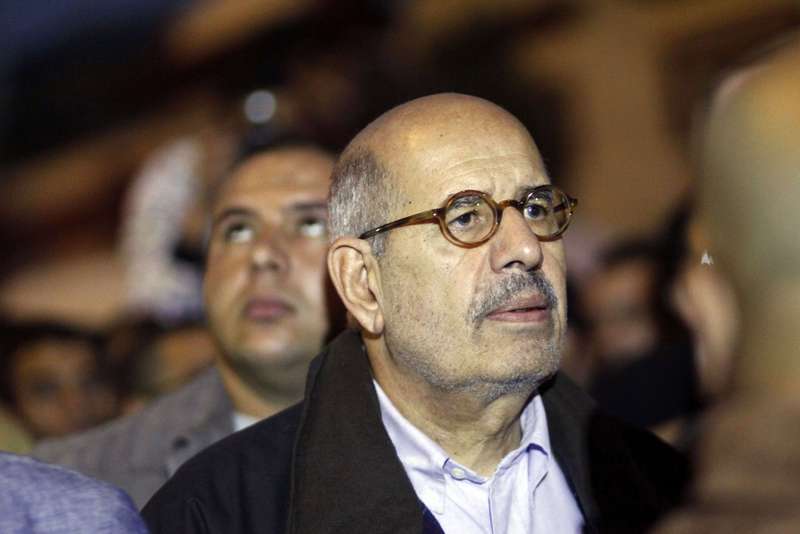

(Photo by Aaron T Rose)

In today’s world, freedom of information is a no longer a luxury, but a necessity, particularly for societies aspiring to establish democracy. According to customs of international law, freedom of information is a fundamental human right that is complementary to freedom of expression.

Today, about 93 countries have passed right to information (RTI) or freedom of information (FOI) laws to empower their citizens and allow them access to information about a myriad of often inaccessible areas, such as government budgets, salaries and developmental and reform plans.

In the vast majority of cases, RTI laws have proven their transformational power over economies and policies, leading to more transparent governance. Jordan in 2007 and Tunisia in 2011 were among the first Arab countries to take steps to pass RTI laws. While it is true that they have been struggling with enforcement, they have at least joined the world in admitting that their populations have the right to know the workings of their government. Now, Egypt is trying to do the same.

Current status of information disclosure

In their 2013 evaluation of the ministries of health and population; housing, utilities and urban communities; environment affairs; and education, the Support for Information Technology Center (SITC, an NGO working on RTI-related issues) tested the disclosure of public information. SITC designed a matrix that corresponds to international criteria and best practices about public information disclosure. It divided the disclosure of information to two types: one where the institution voluntarily discloses information (tasks, contacts, budgets, salaries, and expenses) on official websites; and the second where information can only be accessed by visiting the institution to demand the information in question.

With 104 marking the maximum score any ministry could achieve, Egypt’s highest was achieved by the ministry of environmental affairs, at 44, painting a rather unfavourable picture of the country’s current approach to public information disclosure.

Ahmed Kheir, the executive director of SITC, spoke to Daily News Egypt about the centre’s experience during the evaluation process.

“The report revealed many surprises,” says Kheir. “We went to some ministries seeking to acquire very basic questions, like the number of students in Egypt from the ministry of education, and were told that this was ‘a matter of national security’ and got no number. And this is just one example.”

Ironically, according to Kheir, the reason the SITC had chosen the aforementioned ministries is that the information they harbour is not related to national security, which they had assumed would yield smoother access. However, this was not the case.

“As a pilot experience, we wanted to make sure that reasons such as national security wouldn’t stop us. These four ministries touch the basic rights of Egyptians, but in the future we’ll evaluate the rest of ministries [even those who deal with issues of national security] and other public agencies,” he explains.

Due to the Mubarak regime’s restriction on the flow of information, professionals, researchers, civil servants and journalists working in Egypt have long been aware of challenges to access. Statistics are not always updated or unified, and sometimes do not exist at all. Records are inconsistent and do not always cover longer periods, while official documents are difficult to obtain without security permission. The end result is that the inaccessibility of information for many professions, stakeholders and sectors has represented a major stumbling block the country urgently needs to overcome.

Civil society has made attempts at this over the past two years. It was later joined by the Egyptian government, when it became clear the country could not improve its economic conditions without the RTI law to disseminate information for investors and business entrepreneurs.

Kheir notes that the RTI law’s benefits go far beyond providing a better economic atmosphere for investment, however. “If information is accessible to the public, it empowers people to think and participate in [their everyday and life-plan] decision-making process,” Kheir adds.

In addition to empowerment and participation, the RTI law will boost the transparency of the government and help in the fight against corruption.

However, Kheir among others from civil society organisations, rejects the current RTI draft law, viewing it as “a destructive law that [has gone] against the progress made during the drafting process.”

(Photo by Aaron T Rose)

Controversies in the RTI draft law

Ahmed Ezzat, the director of the legal unit at the Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression, was among the civil society representatives who worked on legislation to regulate the right to information in Egypt.

Their goal has been to tackle the provisions in Egypt’s vast legislative infrastructure that restrict the right to access information.

“We have laws prohibiting information related to military institutions, even if sub-bodies are carrying out economic, industrial and commercial activities that the public has the right to know about,” says Ezzat. “Other provisions allow the parliament and courts to have secret sessions. Secrecy should only be allowed is when matters are related to personal privacy and safety are involved.”

The law governing the Egyptian National Library and Archives, for example, has provisions stipulating that all documents concerned with the “higher policies of the state” could be blocked up to 75 years, thus depriving generations of Egyptians of the use of these documents.

“That’s why over the past two years, as organisations we sat down, met with experts and drafted a law that takes into account privacy and national security, but within a certain definition, [rather than a loose one],” he adds.

According to Ezzat, in 2011 civil society organisations worked alongside with the Cabinet Information and Decision Support Center (IDSC) on the draft and then submitted the draft to the newly elected parliament in 2012. However, the dissolution of parliament brought the process to a halt.

With the formation of a new cabinet, the Ministry of Justice has taken the drafting process under its auspices and has been consulting with the civil society camp. Debates broke out at the negotiation tables, however, over some of the most prominent issues that seem to occur whenever discussing the RTI laws.

According to Ezzat, the civil society camp had suggested prioritising electronic publishing of information to lend the public easy access to official budgets, salaries, and the role of various institutions. However, the Ministry of Justice surprisingly went ahead finalised the draft law and submitted it to the Council of Ministers without the final consultation of said civil societies.

Ezzat explains that the announced draft law includes many points of controversy.

First and foremost, he says it lacks a clear definition of what national security is, despite a suggested definition from a civil society coalition of organisations specialised in RTI matters.

According to the final draft of the law, there is a rather long list included in Articles 32 and 33 of exceptions from the law, such as any information concerning general intelligence, military intelligence. Also on the list of exceptions was “any information that if revealed may endanger national security, the economy, international relations, commercial relations, or military affairs.”

Other exceptions include: personal information that if revealed would jeopardise personal privacy; information about bilateral agreements between institutions that include commercial or professional information of a third party; and policies, decisions and experiments that if disclosed would impact the ability to carry them out. Lastly, the law forbids the disclosure of information that may negatively impact any investigation or hinder the prosecution or arrest of defendants.

Ezzat assumes the security apparatus dealing with national security rejected the definition that existed in previous drafts, adding, “You can’t really exempt an agency; maybe specific units in it, but not the entire agency. This means that the authority is above the people, [above] rights and freedoms.”

As a second point of contention, the National Council for Information (NCI), the institutional body handling the RTI law enforcement, suffers from a lack of autonomy. In Article 9, the structure of the council includes representatives from 14 organisations and government institutions, including: the National Security Council, Ministry of Defense, the Central Agency for Public Mobilisation and Statistics, the Supreme Council for Universities, IDSC, the National Archives, the National Council for Human Rights, the Journalists Syndicate, the General Union for Civil Society Associations, the Chamber of Commerce, and the four most represented political parties in the House of Representatives.

“The NCI in its current form is not really independent,” Ezzat says. “Most of the representatives come from governmental or semi-governmental institutions, and [on top of that,] the president approves its chairman. That’s why we suggested the formation of a new commission from outside of the government [to replace the NCI], which would be held accountable to the parliament,” says Ezzat.

Third, Article 2 of the draft law suggests that the executive regulations of the law, which usually include the details of how to enforce it, be drafted by the prime minister.

“The devil is in the details, and giving the drafting of the regulations to the prime minister is a clear case of how the government will be controlling how the law gets enforced,” he adds.

Fourth, draft’s discussion of information disclosure in Article 5 does not specify the time intervals of when information should be disclosed, instead using the word “periodically.”

Lastly, chapter 6 of the law is dedicated to the penalties of information commissioners who block information from the public. However, according to Ezzat, while the draft law offers penalties, it provides no incentives or protection to whistleblowers, which he believes will discourage people from raising acts of corruption witnessed.

“That’s why we [civil society organisations who worked on the draft law] believe that the final draft submitted by the Ministry of Justice is not up to the international parameters and standards concerned with the freedom of information and does not pave the road for the government’s institutions to have a foundation for the enforcement of the RTI law,” he says.

(Photo by Aaron T Rose)

The other side of the coin

Moustafa Moharram is a senior political communication officer at the Social Contract Center (SCC), a joint initiative between the IDSC and the United Nations Development Program, and has worked extensively on mediating the negotiations between the civil society coalition and the government representatives, particularly from the Ministry of Justice.

In his view, the current draft is empowering and should establish an “unprecedented level of transparency in Egypt” if passed by the Shura Council.

Responding to the issues and controversies outlined by Ezzat, Moharram believes that there are many schools of thought for defining national security.

“There is the realist approach which focuses on military power and institutions. A liberal approach would include something different, as would the constructivist approach, so the debate is big and requires a level of maturity among all sides to come up with a definition,” he says.

According to Moharram, as a “confidence building” measure with the security apparatus in Egypt, the draft was non-confrontational about the definition of national security. However, he says that it abides by international parameters while “tailoring itself to Egyptian context.”

Moharram thinks that to the means to discipline any possible abuse of a lack of definition of national security lie in Article 34, which stipulates that “any information on crimes that lead to human rights violations, corruption or environmental threats should be disclosed even if directly related to national security.”

As for the exemption of military institutions, Moharram explains, “We didn’t exempt the military as an institution; we exempted one agency under its umbrella, which is [intelligence services]. At the end of the day, the oversight of total or partial disclosure or blockade of information is in the hands of the independent NCI. It will have the final say in the demands and petitions coming from different institutions to conceal some of their information.”

Unlike Ezzat, Moharram believes the NCI in its current form is indeed independent from the government. However, he thinks that civil society needs to exert additional effort and lobbying to improve the autonomy of its members.

“I personally believe we did our best in coming up with this law,” says Moharram. “We had a consultative body where people from civil society and the ministry of justice debated and came up with a draft. Yes, we might have disagreed about certain methodologies, but the current draft, if passed would improve Egypt’s status in many aspects.”

No passage!

Despite his optimism over the content of the current RTI draft, Moharram thinks it will not pass because its approval would hold too many government institutions to account for their practices.

According to Toby Mendel, the World Bank consultant who evaluated the final RTI draft in June 2013, the law is of a “progressive nature.” He noted that if this final draft was passed, the draft law would rank 8th globally among 93 countries who have passed RTI laws. This rank was estimated according to a global assessment methodology on RTI-Rating.org. Mendel admits that the law was weak in certain areas, such as the appeals system, providing protection for whistleblowers and providing a clear definition of national security, which in a statement he called “a concept which has historically been roundly abused in Egypt.”

Moharram meanwhile explained, “We’ve sent the law and Mendel’s June assessment of the draft to the Council of Ministers, the prime minister, the presidency and I personally hold them responsible if they modify any provision or clause to distort the RTI draft law. [If they do,] we will reveal it to the public.

“Egypt would be among the top ten countries globally if this draft were to be passed. It’s our right to keep the draft as is or improve on it.”

It is estimated to take a year and a half for the law to come into effect. This time would be used to prepare the government institutions with the needed foundations to make information accessible to the public. “However, one of the main challenges to enforcement is bureaucracy,” says Moharram.

He concludes, “We might disagree with the civil society coalition on the methodology, but the draft we came up with is technically sound, so let’s not kill the RTI law with friendly fire. At the end of the day, we belong to the same camp and we want this law to exist.”

*****

Whether the draft law passes or not, people in post-revolutionary Egypt are keeping an eye on the government. Egyptians continue to push for more transparency and better communication about the predicaments facing their country; they want to know why there are huge discrepancies in wages, how much leading officials are paid, and what budgets are allocated for the operation of each ministry. Sooner or later, they are likely to mobilise for better access to this information.