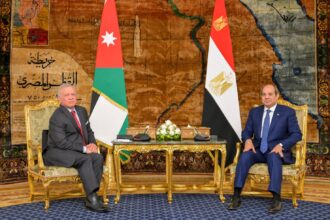

How democratic last week’s events in Egypt were will continue to be debated. Democratic or not, this is an excellent opportunity to set the economy in a better direction. Information will be critical for improving the economy. It will also give credibility to these events as being part of a democratic process.

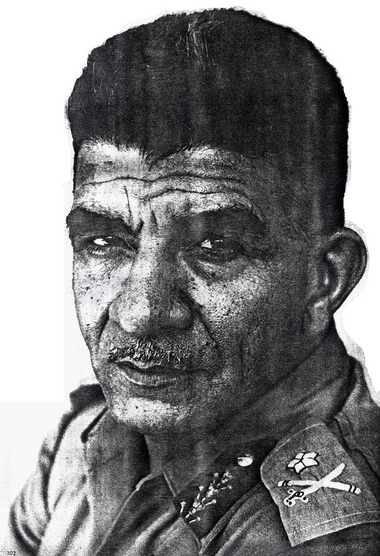

Democracy is not necessary for good economic growth. Politicians can easily prioritise special interests in democracies as they can in authoritarian regimes. An authoritarian leader may direct economic strategies for a country’s growth better than a democratically elected one. South Korea’s great economic success can easily be traced to major strategic decisions of a former general, made during a less democratic period following a coup d’etat.

However, democracies do help economies through information. Democratic countries have stronger freedom of information legislation and greater disclosure of government activity, such as more transparent national budgets, government contracting and expenditure. Business tends to have better access to information for planning and decision-making. Consumers are often better informed and protected by a freer civil society.

Under democratically elected former president Mohammed Morsi, information was even more difficult to obtain than during former president Hosni Mubarak’s time. Although the Egyptian government had long been criticised for its lack of budget transparency, Morsi’s cabinet was even less transparent. Many argued that civil society was more stifled. Key government figures would give inconsistent information, even on important matters like the International Monetary Fund loan negotiation.

Moving forward, information will be one of the most important factors for economic recovery. For Egypt to move back to a state of steady and healthy economic growth requires both restoring investor confidence and political acceptance of already late but very necessary key economic reforms. And neither of these is likely to occur well without extensive and smart use of information.

The new ‘technocratic cabinet’ and cabinets that follow will learn from Mubarak’s final economic management team. They effectively managed investor confidence through a well-communicated unified vision for Egypt’s economic growth and focused on giving investors information. It paid off. Investment profiles of the country often noted this positively and likely, it was a factor in the high economic growth at the time.

There is a risk of poor communication with technocratic cabinets. In instances, these types of cabinets underestimate the importance of communication because they are less like politicians and more like subject matter experts. More skilled politicians in the arena can undermine prudent economic decisions by being better communicators and framing issues in an unconstructive way, potentially leading to more political obstacles to economic recovery. This is a risk in Egypt now. Information and communication will help reduce these risks.

For the economy to begin to recover, the Egyptian government, no matter who is president, will have to implement long overdue economic reforms. That is very difficult to do under any circumstances, but almost an impossible task in the midst of high political tensions. Here again, information will be key. Citizens tend to be more tolerant of economic reforms that reduce benefits and raise taxes if there is more transparency on the motivations, necessity and best approach for the measures. A good communication strategy for future economic reforms is essential and could make a world of difference in the acceptance of measures taken.

Information will also help with economic recovery through better decision-making. Previously, much government planning and resource allocation was principle, rather than evidence-based. Decisions on programs and benefits were not informed by how efficiently money was used or how best to spend government money in the best interest of the Egyptian people. The Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation uses very little data and evidence in its work. Neither is very integral to many of the government planning processes. Integrating both would save the country a lot of money, a good thing given the budget crunch. It could also help to better deliver on the aspirations that the Egyptian people have continuously demanded in terms of justice and opportunity.

Information sharing could help economic recovery in Egypt further, by better supporting the private sector. This is true of basic information that has largely remained unclear since Morsi took office, like what to expect for changes in tax rates; but also more sophisticated information that businesses in Egypt often lack, like market and consumer information that are important for better planning and decision-making. Even though some of this information is collected by various government agencies, it is usually unavailable. If new policymakers showed a stronger inclination to information sharing, the private sector might perform better.

Information, both its use and sharing, is essential in moving Egypt forward towards economic recovery. Neither restoring investor confidence nor instituting inevitable key economic reforms can take place very well without it. And both are desperately needed. In Egypt now, more information sharing and communication would help reverse the trend of the last year towards less transparency and less clarity. This last week has given the country a fresh opportunity, though considered by some as undemocratic. But if the move translates into citizens being able to better hold the government accountable for decisions and more access to information for the protection of economic rights, then it might just be democratic after all.