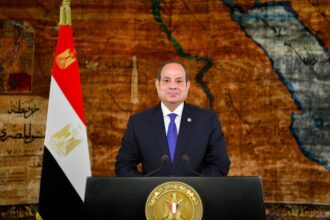

(Photo from Al Masar Gallery)

Artist Hazem Taha Hussein’s latest collection at Al Masar Gallery explores Egypt’s current political turmoil through the use of symbols and patterns well known in Egyptian society. The paintings are filled with subdued colours, Coptic symbols and motifs associated with the community. In some of the paintings, the figures of family and angels are covered with Islamic geometric patterns, giving the observer the notion that you are looking in at someone from behind an Arabesque window.

The figures within the paintings become a constant mirage that moves with the eyes; at times, they disappear and at others, they are the only thing visible. However, their existence remains hesitant and disruptive. In addition to the Eastern elements, Hussein blends Western aspects of living that have become paramount to Eastern societies, expressing the overlapping values seen on a global scale. In the painting “Supporting the Leader”, Mickey Mouse makes an appearance.

“Mirage II is a continuation of the series of exhibitions which goes beyond the optical nature of a mirage, but depends on producing hazy social images and copied cultural ideas,” explained Hussein in a printed statement. In addition to expressing the mixed nature of the Egyptian community, the exhibition also documents how people communicate with each other within society.

“Most of us like [the idea] of living with legend, and use strange symbols to communicate,” Hussein said. People have become obsessed with decoding hidden messages and symbols, and that is what Hussein is trying to portray in his paintings. There is a desire to uncover the unknown and go beyond logic and materialistic findings. “It shows through the eyes’ movement, the face features and body language,” Hussein wrote.

Through the use of mixed codes, the symbols lose their original meaning and the paintings tell a different story. “If we take famous American cartoon characters like Mickey Mouse or the Catholic angel and mix it with the heads of veiled women, along with an Islamic pattern background, we find that the pattern has lost its original ideological function, and instead Mickey Mouse became an Egyptian Mickey. It becomes funny and does not represent Disney or the United States and the women [in the painting] are instead telling stories of the Egyptian-Greek societies of the forties,” Hussein explained.

The paintings also prompt questions about their hidden figures and symbols, and why they hide behind geometrical patterns and religious elements. “We might like looking at these symbols as if they were telling us a story about public and private events. In time, the work’s elements gain some dynamic and interesting values which could explain the lurking of things behind Eastern and Western aspects,” Hussein concluded.

The exhibition continues until 3 December in Al Masar Gallery in Zamalek.