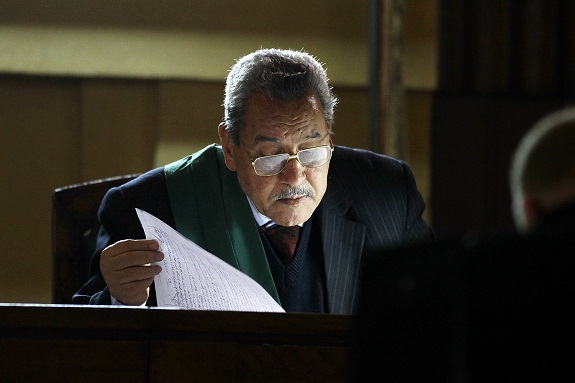

(Photo courtesy of Qamos al Thawra)

A new website, Qamos Al Thawra (‘Dictionary of the Revolution’), seeks to collect the constantly changing catchphrases of the Egyptian revolution.

Since protesters first hit the streets in 2011, the country has been coining new terms in aamiyya, Egyptian colloquial Arabic. The new website aims to collect ideas, words, and comments about the evolution the language.

Project founder Amira Hanafisaid said she hopes the website will become a space where the community can share stories and ideas, defining terms such as “feloul” or “third party”. The website, written in aamiyya, is an extension of a larger effort to publish a dictionary of words and phrases that have emerged since the 25 January Revolution.

Using a set of 160 vocabulary cards to provoke discussions, the project seeks to explore four main categories: objects, places and events, characters and concepts. The current vocabulary set includes words like thugs ‘Balatagiya’, rebel ‘Tamarod’, deep state ‘Al Dawla Al Amiqa’ and ‘Set El Banat’, an expression used to refer to the woman in the blue bra who was stripped by military soldiers late in 2011.

The project, which is funded by The Arab Fund for Arts and Culture, accepts different forms of contribution, including text, photos, or audio files submitted though the website, email, or social media. “Qamos Al Thawra” is also interviewing Egyptians from all over the country.

In its own words, the website describes itself as “a free space for everyone to talk,” giving people the chance to express their unique voice.

It is written in aamiyya, which sets it apart from most cultural projects.

“As a person who grew up not speaking Arabic, I find it easier to understand ‘aamiyya’ than ‘fus-ha’ [classic Arabic],” Hanafi said. “Since the idea first came from people speaking, we wanted to document this the way we as Egyptians speak it not read.”

Hanafi came up with the idea in the wake of the 2011 uprisings, when she said people were “talking, discussing their ideologies in the streets and expressing themselves in this vocabulary”.

She didn’t secure funding for the project until mid 2013, however, right before the ouster of former president Mohamed Morsi. At that point, she said, artists and researches working in public spaces, especially for those addressing political topics, had to start treading more carefully.

“The atmosphere became less open”, she said. “This made me think about whether I should do it, how I should do it.”