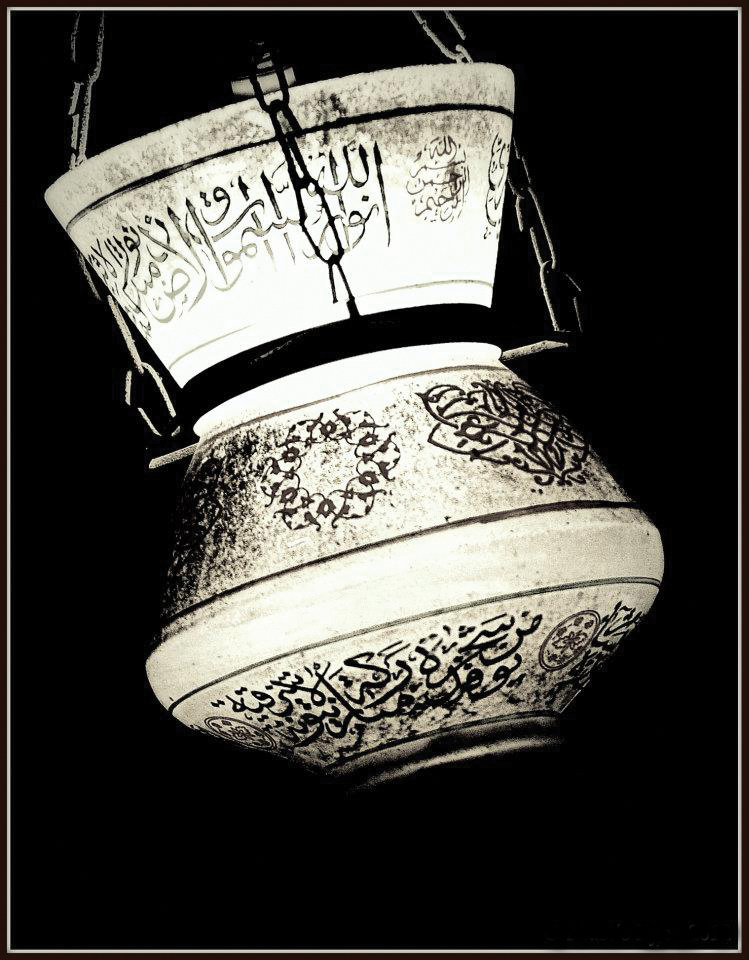

(Photo Public Domain)

A prophecy in Islamic hadiths (messenger’s sayings) stipulates that oppression, tyranny, and darkness will prevail all over the globe. Eventually, the Caliph Mehdi Muntazar (the awaited redeemer of Islam), who like the Prophet himself will be named Mohammed bin Abdullah, will take the lead and unite the Muslim Ummah (community of believers).

The prophecy says that Islam will gain an upper hand and will be firmly established in the land. Justice, peace and equity will prevail for seven years, the period of the Mehdi’s reign. He will arrange a Muslim army and will be on the verge of leading it to defeat the Dajjal (anti-Christ), when Jesus will return and kill the Dajjal.

Then comes the apocalypse.

Today, this prophecy has strong political implications, and not just for Muslims.

“The Awaited Mehdi is a myth that states are built on. The myth feeds on itself,” said Ashraf El-Sherif, comparative politics professor at the American University in Cairo (AUC).

The word ‘caliph’ is the English form of the Arabic word ‘khalifah,’ short for Khalifatu Rasulil-lah (Successor to the Messenger of God). The caliph is supposed to make all laws in accordance with the Qur’an and the Sunnah.

The latest version of the caliphate was announced last June, when Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, leader of the Islamic State in Iraq and the Sham (ISIS), proclaimed himself khalifah and amir al-mu’minin (prince of the believers). He also renamed the organisation “Islamic State”.

ISIS is obsessed with the emergence of the Mehdi, and is preparing for his reign, claimed Lennart Sundelin, professor of Middle East history at AUC.

Islam’s Holy Prophet Mohamed said that there shall be no true Islamic caliphate starting 30 years after his death and up until Caliph Mehdi emerges, said Al-Azhar Sheikh Mohamed Yehia Al-Kattani.

(Photo Public Domain)

The Islamic Prophet united religious and political authority. After his death in the year 632AD, there was no agreed upon succession plan. Civil wars broke out over the right to be the caliph, and his power and authority. The fifth caliph, Muawiya, appointed his son as a successor, setting the family dynasty pattern of the caliphs up until the twentieth century. There is a lot of evidence that the caliphate was an ad-hoc institution rapidly evolving throughout the centuries, according to Sundelin.

“The success of those dynasties made them an important part of why there is nostalgia for a caliphate [nowadays],” he added.

A caliphate is composed of several states, explains El-Sherif. The four Rashidun (Righteously Guided) caliphs invaded other countries to expand the caliphate, said El-Sherif. The Rashidun caliphate initiated expansion of Islam beyond Arabia. The caliphate ended up conquering all of Persia, besides Syria, Armenia, Egypt in 639, and much of North Africa, Spain, and Portugal.

Different dynasties succeeded one another over the centuries, and on occasion more than one caliphate co-existed at the same time, as in the case of the Fatimid caliphate in Egypt and the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad.

Until the early twentieth century, the Ottoman caliphate still ruled much of the Middle East, though the empire had already entered a long period of decline. During the First World War, the Ottoman Empire called for jihad against the Allies and it was its defeat in the war that eventually led to the fragmentation of the caliphate and its abolishment in 1922. Turkey became a republic and the Islamic State was no more.

The idea of a caliphate re-emerged on several occasions in the following decades but never managed to take hold. King Farouk of Egypt attempted to use the notion to unite Egypt and the Arabs. Various political groups also called for it, such as the Caliphate Movement in India, the Tahrir Party in Palestine, and the European Caliphate Movement. ISIS is the latest organisation in a long list.

Sundelin does not see a future for the ISIS caliphate, which he believes is the product of local sectarian issues. “Their version [of a caliphate] is simplistic and crude.”

Per contra, El-Sherif said the balance of power in the region indicates that ISIS is here to stay.

ISIS will eventually turn into a state, albeit a repressive dictatorial one, with its own borders, military, and bureaucracy he said. It will impose taxes and conduct trade relations with other states.

El-Sherif said that the world will be forced to deal with ISIS, including the “pragmatic” United States, which is currently the leader of an international coalition against it. For political theorists of the realist school, like Niccolò Machiaveli and Henri Kissinger, “legality does not matter. What matters is power,” said El-Sherif.

El-Sherif argued that it is possible that ISIS could gain state recognition and flourish, saying that Israel, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia are all states built on a religious basis.

(Photo Public Domain)

The ultraconservative Wahhabi sect played an essential role in the establishment of Saudi Arabia, and underwent a similar path to ISIS. Ideologically, there is no difference between ISIS and Wahabbism, El-Sherif said.

ISIS, or any other entity wanting to form a caliphate, will have to expand either through military conquest or through the power of ideas. If their model is appealing, states could fall in their hands in a manner that matches Syria’s approach to former Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser, asking for an alliance.

Yet, even if they do succeed, ISIS’s understanding of Islam is incorrect, said Sheikh Al-Kattani. “They have psychological problems… what they are calling for should not be followed.”

Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula is in the midst of an armed conflict between militant groups and the Egyptian state. The militant group Ansar Beit Al-Maqdis pledged allegiance to ISIS on 10 November and renamed itself “State of Sinai”.

“[The problem] in Sinai is no longer terrorism. It’s a local rebellion led by armed militant groups. Control is lost there,” said El-Sherif.

Other Islamist entities have distanced themselves from the ISIS caliphate. While the Muslim Brotherhood has always wanted to resurrect the Islamic caliphate, the Brotherhood and ISIS cannot be allies, according to El-Sherif. “ISIS views the Brotherhood as infidels.” Yet, the Brotherhood will manipulate ISIS, as “any success ISIS achieves is an opportunity for gloating over [Egyptian President] Al-Sisi’s deficiency,” El-Sherif said.

The Muslim Brotherhood leaders cannot condemn ISIS in a direct manner. “The Brotherhood’s youth are furious,” said El-Sherif. “ISIS is a tempting model for them after the failure of a democratic Islamic state [in Egypt].” El-Sherif pointed out that using weaponry and force appears to be more successful in forming a caliphate than election polls after the ouster of former president Mohamed Morsi, which may attract some people.

A rekindling of the alliance between Al-Qaeda and the ISIS leaders is also unlikely. ISIS is more ideologically extreme than Al-Qaeda. They disagree over who truly represents the Islamic religion and, while ISIS aims at building its caliphate, Al-Qaeda’s aspiration is overthrowing the US, said El-Sherif.

The world is moving towards a new order. The current debate incorporates transnational political entities versus sub-national units based on cultural or religious identities.

Will the world end after a “real” caliphate is established? The Alamat Al-Sa’a Al-Kobra (Major Signs of Judgment Day) in Islam hypothesise just that. But in modern political discourse, El-Sherif acknowledges that there is no place for metaphysical theories about the apocalypse. Perhaps, this should be reconsidered.