(AFP File Photo)

By Shereen Kamal

Ahead of the parliamentary elections, which are expected before March 2015, Tamarod’s Arab Popular Movement was among tens of political parties gearing up to field candidates.

The group’s request to establish a political party, however, was rejected by the Supreme Electoral Commission on 3 December. The commission then referred the case to the Supreme Administrative Court to decide on its legal status.

Tamarod’s spokesperson Mohamed Nabawi told state media that the commission rejected the party, citing regulatory issues and stressing that the party is youth-organised and lacks necessary financial and legal support.

The party intended to have a separate organisation to train cadres, which the commission rejected, Nabawi said.

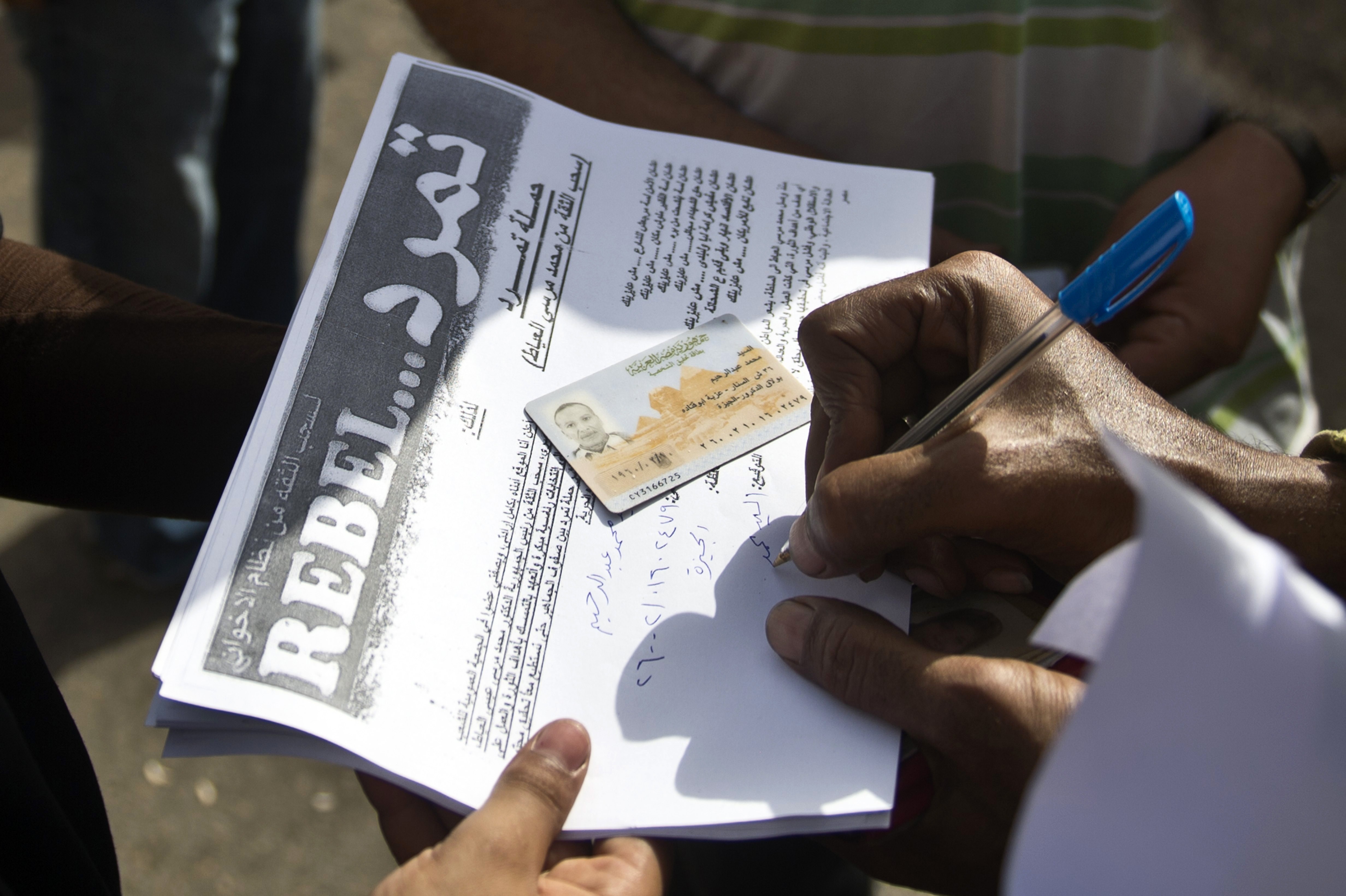

Tamarod, or “Rebellion”, was founded in early 2013 to force Islamist president Mohamed Morsi and his government to step down. To this end, it stated that it would collect 15m signatures calling for early presidential elections.

Other opposition groups formed part of the movement, including the 6 April Youth Movement, Kefaya, the National Salvation Front, and the Revolutionary Socialists, who participated in gathering signatures nationwide.

Following mass demonstrations against Morsi, the military ousted him from power on 3 July 2013.

However, the once united opposition front that participated in million man marches demanding the ouster of Morsi, now stands divided.

Tamarod’s coordinator in Giza Mohamed Hassan said that after July 2013, the movement “has gone from seeking to bring down the regime to trying to rebuild the state, turning its popular support into party bases”.

However, Mohamed Nabil, a member of the 6 April Youth Movement, had a different take. “There is no real democracy at the moment that could allow for the proper formation of parties that participate in the political scene,” he said.

After the toppling of Morsi, liberal activists criticised Tamarod for its apparent support of the military.

According to Abdelrahman El-Gohary, Kefaya’s general coordinator in Cairo: “The popular forces were defeated after 3 July 2013 because of this type of fragmentation.”

Nabil, of the 6 April movement, said that Tamarod sought to “monopolise the discourse of toppling Morsi through the collecting of petitions, even though other movements like 6April and Kefaya played important roles”. He added that “after July 2013, certain members of Tamarod took over the organisation and transformed its vision in order to suit their own political aspirations”.

One of the main sources of contention was that Tamarod’s initial objective was to pressure Morsi to hold early presidential elections. However, after the military takeover the movement’s leaders expressed their support for the military intervention in politics and interim president Adly Mansour’s military-backed government.

El-Gohary, of Kefaya, said he believes that the political forces could have succeeded in bringing about change at the time of the 30 June protests, had it not been for their disunity.

Two of the movement’s founders, Mahmoud Badr and Mohamed Abdel Aziz, were members of the post-30 June 50 member constituent assembly that was in charge of drafting a new constitution. The only instance in which the movement actually criticised the post-Morsi regime was when the Protest Law was issued in November of 2013.

Mohamed Heikal, a former member of Tamarod who recently left the movement citing “personal reasons”, stated that “criticisms directed against Tamarod stems from political rivalry. Movements like 6 April and Kefaya wanted people to believe that 25 January was the sole revolution because they believe they were a major player in it, and so they like to denounce the 30 June revolution, which was spearheaded by Tamarod. Today, Tamarod is more popular and able to mobilise more people than both these movements.”

Other disagreements within the movement itself caused splits that ultimately led to the suspension of key members and the formation of the Arab Popular Movement Party by a number of former Tamarod members.

In December of 2013, the movement publicly stated that it would endorse Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi’s presidency if he decided to run for office. However, when Hamdeen Sabahy stated he would also run in the election, splits within the movement became obvious to all, due to the way the campaign process was handled on social media.

Although Tamarod’s official stance was to support Al-Sisi, both their Facebook and Twitter accounts were campaigning for Sabahy. This was the time when the group started suspending some of its key members, like Mohamed Abdel Aziz and Hassan Shahin, for political differences with the leadership.

Mahmoud Badr, who is now in charge of Tamarod, was actually part of Al-Sisi’s presidential campaign. This was when the movement announced that it was going to make the transition to a political party following the elections; a point that was also criticised by the Abdel Aziz camp, who felt that Tamarod’s role was over.

“The Arab Popular Movement” was the name given to the party which was registered on 6 November 2014.

“Over 90% of the party members are from the youth,” said Mohamed Hassan, Tamarod’s coordinator in Giza. While the law requires any new party to get a minimum of 5,000 endorsement forms from at least ten out of Egypt’s twenty-nine provinces, the movement was able to collect 6,200 endorsements from over twenty-six provinces.

Hassan also stated that the party intends to nominate 50 of its members in the next round of parliamentary elections, with Mahmoud Badr being one of them.

However, on 3 December, the Supreme Electoral Commission rejected the establishment of the party based on provisions within the political parties’ law, and referred it to the Supreme Administrative Court to decide on the party’s legal status. Tamarod’s spokespersons were not available to comment on the situation.

Is Tamarod still relevant today, after it has completed its mission of getting rid of Morsi? According to Hassan Nafaa, political science professor at Cairo University and former coordinator of the National Association for Change, “Tamarod was an occurrence during a specific emotional state for a large portion of the population, and for a specific period of time, particularly after the constitutional decree of November 2012.”

However, Nafaa claims that “this state has ended, and that evolving or hijacking the movement into another political form will never be as effective”.