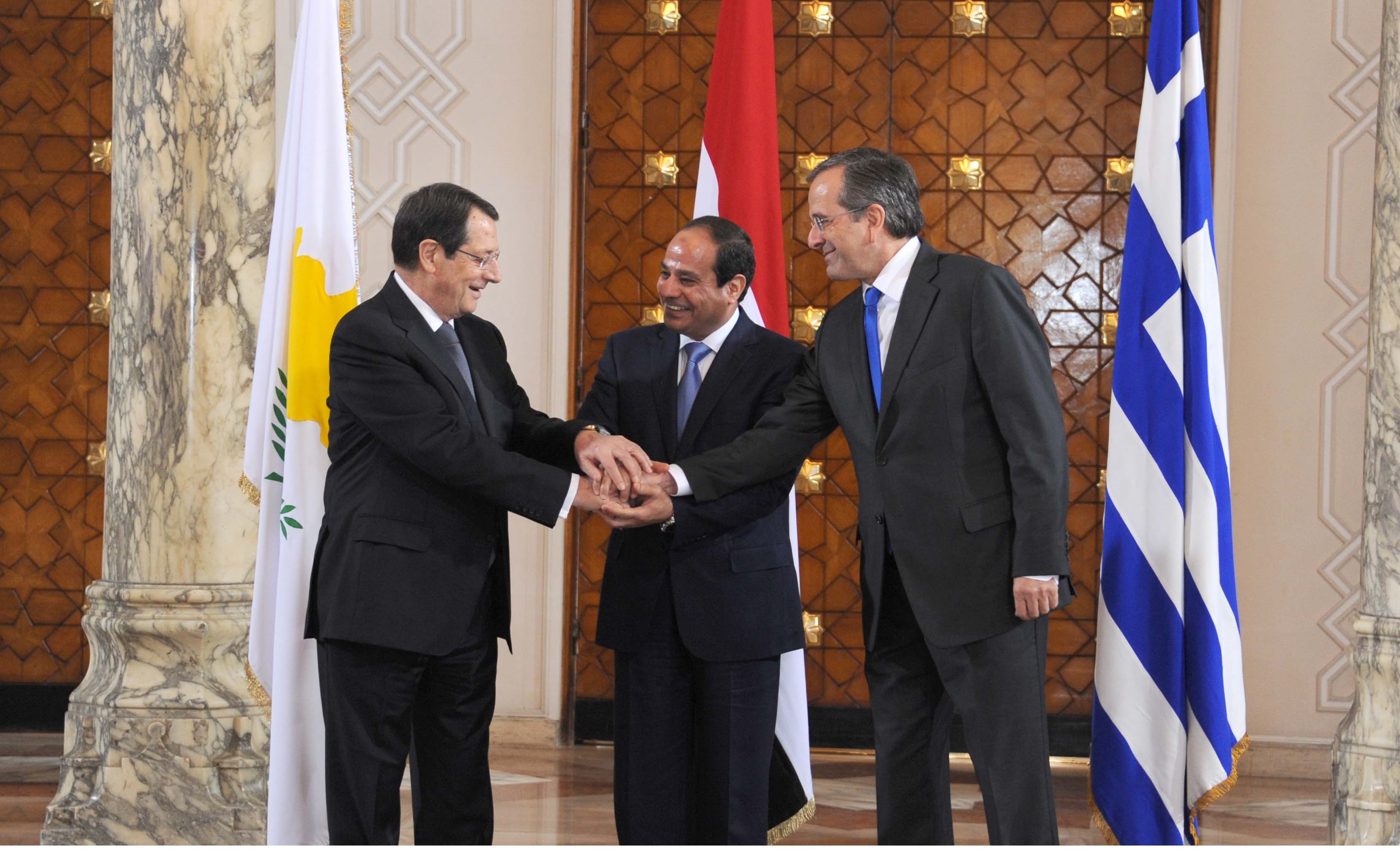

(AFP File Photo)

The passing of the 2015 spending bill in the US Congress on Saturday night has strong implications for the partially frozen annual military aid to Egypt.

The $1.1trn omnibus budget, which passed its final Senate vote 56 to 40, encompasses funding for most of the US government’s operations, its federal agencies, as well as aid to foreign states.

It will impose heavy cuts on agencies, including the Internal Revenue Service and Environmental Protection Agency, and obstructing the White House’s attempts to transfer Guantanamo prisoners to American soil.

It also appears set to allow a resumption of halted military aid to Egypt.

Like the previous year’s budget, the bill retains democratic requirements for the full disbursement of the annual $1.3bn military and economic aid to Egypt. It also allows for Secretary of State John Kerry to supersede the conditions on grounds of “national security”, a waiver absent from the previous spending bill.

The bill maintains that before the first $725m of aid not designated for military training and counter-terror operations in Sinai can be released, Egypt must hold free and fair elections, respect civil society organisations and freedom of expression. It also called for the release of US political prisoners in Egyptian jails. The remaining support will be delivered later subject to continued Egyptian adherence to the conditions.

Kerry has the authority to make a submission to Congress in private “classified form” should he believe that it is in the US’s best interests to release the rest of the aid.

A White House aide disclosed that the change in policy follows strong lobbying from Egypt and allies including Saudi Arabia, pro-Israel lobby AIPAC, UAE and Jordan. President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi is seen as an important regional player against Islamists in the region, according to Washington-based media site Al-Monitor.

The previous budget passed in mid-2013 followed the ousting of democratically elected former president Mohammed Morsi, as such democratic transition conditions were placed on aid that the US administration was not allowed to waive. The Secretary of State had to certify Egypt’s “credible progress toward an inclusive, democratically elected civilian government through free and fair elections”.

Consequently, the US halted a transfer of F-16 fighter jets, M1A1 tank kits, Harpoon missiles and Apache helicopters during the interim-government. The resumption of the supply became a key element of John Kerry’s and Al-Sisi’s negotiations in the latter half of this year.

A partial resumption of $575m was announced to coincide with a June meeting between the two politicians, with Kerry saying afterwards that Al-Sisi gave him a “strong sense of his commitment” to follow up on human rights and judicial integrity progress in the country.

Days after the meeting, Egypt made international headlines for the sentencing of three Al-Jazeera journalists to jail for up to 10 years, the judicial process and evidence used in court was widely criticised for being shaky.

With Kerry’s partial resumption of military aid in June, the US’s interest in human rights and democratic transition in Egypt appears to have been sidelined by regional security issues, such as the fight against Islamic State.

The trade-off between security, and democracy and human rights, is rejected by some. “Congress should not be making it easier for the administration to avoid confronting the issue in its dealings with the Egyptian government,” Brian Dooley of Human Rights First said in a 10 December statement.

Major military support from the US began in proper following the 1979 Egypt-Israel peace treaty; partly to guarantee security for Israel and partly for Cold War strategy to realign Egypt from the Soviet Union to the US. The Atlantic Council report notes that over the course of the past 35 years, the US has provided over $40bn worth of defence aid to Egypt, second only to Israel.