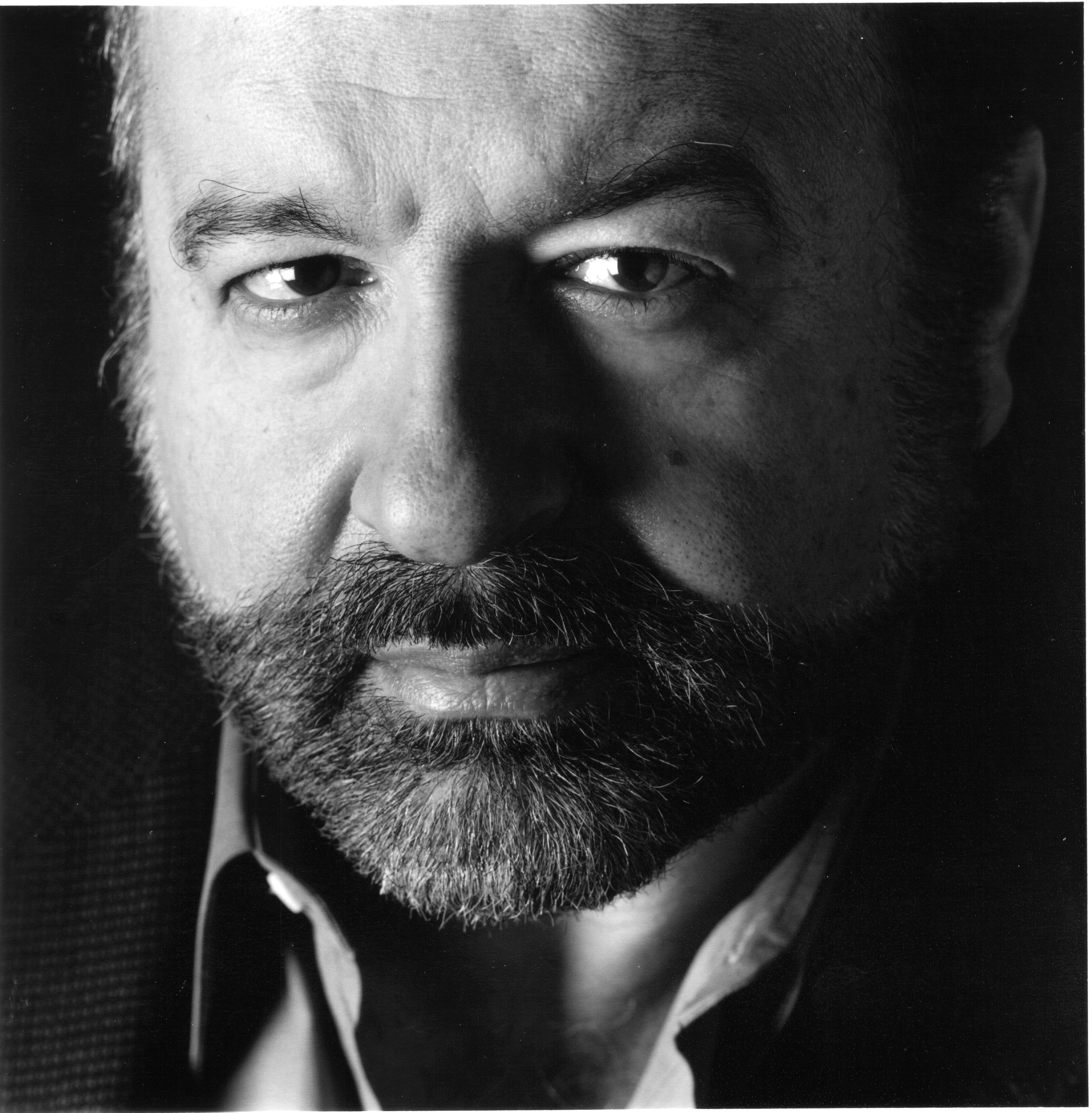

By Hernando de Soto

Thomas Piketty’s, Capital in the 21st Century, has attracted worldwide attention, not because he crusades against inequality – many of us do that – but because of its central thesis; based on his reading of the 19th and 20th centuries: that capital “mechanically produces arbitrary, unsustainable inequalities” inevitably leading the world to misery, violence and wars, and will continue to do so in this century.

So far, Piketty’s critics have offered only technical objections to his number crunching, without contesting his apocalyptic political thesis, which is clearly wrong. I know this because over the last years my teams conducted research in the field exploring countries where misery, violence and wars are rampant in the 21st century. What we discovered was that most people actually want more rather than less capital, and they want their capital to be real and not fictitious.

Tahrir Square, Cairo: The City of Dead Capital

Thomas Piketty, like many western academics on a tight budget, when faced with poor and nonsensical statistics outside Western nations, instead of going to the field to do his own sampling, takes European class categories and statistical indicators and extrapolates them onto such countries. He then uses them to draw global conclusions and a universal law, ignoring the fact that 90% of the world population lives in developing countries and former Soviet states, whose inhabitants produce and hold their capital in the informal sector; that is to say, outside of official statistics.

This flaw has implications that go far beyond mere accounting: It turns out that the kinds of violence that erupted in places like Tahrir Square, Egypt, in 2011 occur where, according to our field studies, capital plays a decisive if hidden role that Eurocentric analysis cannot perceive.

At the request of the Egyptian Minister of the Treasury, we investigated 120 mostly Egyptian researchers, not only studying official documents but also acquired local information on the ground, going door to door, to get data that allows the government to test its conventional statistics for truth and completeness. We discovered that 47% of so-called “labour’s” yearly income is “capital”: Almost 22.5 million workers in Egypt earned not only a total of $20bn in salaries, but additionally $18bn more through returns on their unrecorded capital. Our study showed that Egyptian “workers” own an estimated $360bn in real estate, eight times more than all the foreign direct investment in Egypt since Napoleon’s invasion. It is no wonder that Piketty, looking only at official statistics, missed all those facts.

The Arab revolutions and the wars for capital

Piketty worries about wars in the future, and suggests that they will come about in the form of a rebellion against the inequities of capital. Perhaps he hasn’t noticed that the wars over capital have already begun right under Europe’s nose in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Had he not missed these events, he would have seen that these are not uprisings against capital, as his thesis claims, but for capital.

The Arab spring was triggered by the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi, in the former French colony of Tunisia, in December 2010. Because official Eurocentric statistics classify all people who are not working at formally-recognised firms as “unemployed”, it was not surprising that most observers quickly labelled Bouazizi as an “unemployed worker”. But this classification system missed the fact Bouazizi was not a labourer, but a businessman since the age of twelve, who very much wanted more capital. A Eurocentric classification system blinded us to the fact that Bouazizi in reality was leading an Arab industrial revolution of sorts.

It wasn’t just him. Thereafter, we discovered that 63 other entrepreneurs, within two months, all inspired by Bouazizi, attempted public suicide throughout MENA, and sparked millions of Arabs to pour into the streets, toppling four governments nearly immediately.

Over two years, we interviewed about half of the 37 self-immolators who survived their burns, and their families: all were driven to suicide for being expropriated of what little capital they had.

Some 300 million Arabs live in the same circumstances as the entrepreneurial self-immolators. We can learn several things from them.

First, capital is not at the root of misery and violence, but rather the lack of it. The worst inequality is not to have capital.

Second, for most of us outside the West, not prisoners of European categorisations, capital and labour are not natural enemies, but intertwined facets of a continuum.

Third, the most important constraints to the development of the poor arise from their inability to build and protect capital.

Fourth, the willingness to stand up to power as an individual is not exclusively a Western trait. Bouazizi and each of the self-immolators are Charlie Hebdo.

Fictitious capital and the European economic crisis

I couldn’t agree more with Piketty when he says that lack of transparency lies at the heart of the European crisis, ongoing since 2008. Where we part ways is at the solution he proposes: assembling a giant ledger – a “financial cadastre” – that includes all financial paper.

That makes no sense, since the problem is that European banks and capital markets abound in what Marx and Jefferson called “fictitious” capital or paper that no longer reflects real value. Why would anyone want a cadastre of trillions of dollars and euros of obscurely bundled derivatives, based on untraceable or poorly documented assets that are swirling mindlessly in European markets? A cadastre that merely sums up the “value” of all these instruments would therefore do nothing more than report a meaningless number for fictitious capital. Particularly considering that a major reason why the European economy is barely growing is that no one trusts the financial institutions that are holding this paper.

So how can we go about creating a cadastre of reality and not fiction? How can governments get a grip on economic facts that can be tested for truth in a global market full of illusory paper? How can we locate, fix and control something as immaterial and transcendent as capital? Of all people, the French have supplied the answer with their property record-keeping systems developed before, during and after the French revolution. In those days feudal record-keeping systems couldn’t keep up with the growing force of expanding markets, and recessions flew out of control as trust among the French disappeared and people took their frustration to the streets. French reformers responded not by trying to cadastre a messy financial system, but by creating radically new fact-gathering systems that mirrored reality and not fiction.

Simple and brilliant: Property records, as opposed to financial records, are written up in rule-bound and publicly accessible registries and contain all the knowledge available that is relevant to the economic situation of people and the assets they control. No one can afford to be incorrect about the amount of capital they own, as they would otherwise lose it.

In French reformer Charles Coquelin’s words, France was able to modernise when throughout the 19th century the country learnt to record property and thus “pick up the thousands of filaments that businesses are creating between themselves, and thereby socialise and recombine production in a mobile fashion”.

Piketty has his heart in the right place, but his papers are in the wrong archives. The issue in the 21st century in the West is asset-less paper, and everywhere else it is paperless assets.

How do you deal with misery, wars and violence at a time when the most of the records of the world have stopped representing crucial aspects of reality? French history, particularly the French revolution, is a good place to start.

Hernando de Soto is the author of the Mystery of Capital