With the celebration of the government’s latest “success” in inaugurating the 1.5m acres reclamation project a few weeks ago in the Al-Farafra Oasis, President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi’s regime has been reaffirming the fight against terrorism and ensuring the stability of the Egyptian state.

This has been undertaken, in large part, through initiating large-scale national projects that overtly appeal to nationalist sentiment and aim to revitalise the flailing Egyptian economy. Yet, in a situation that recalls that of the inauguration of the New Suez Canal, the 1.5m acres project has not been immune to criticism. Just like the former project, the Egyptian state’s projected expectations outpace both their capacity and the reality on the ground.

Both projects have been inflected by a nationalist rhetoric, a rhetorical haunting of that which was once employed by president Gamal Abdel Nasser during the 1950s and 1960s, despite the incomparable historical and socio-political contexts of the two statesmen and governments.

To interrogate the feasibility of certain aspects of those projects provides an inlet into the mentality of the post-3 July regime. In fact, it is critical to attempt to infer the real boundaries of this rejuvenated approach, especially in the later project, which has a wider social dimension and more profound outcomes.

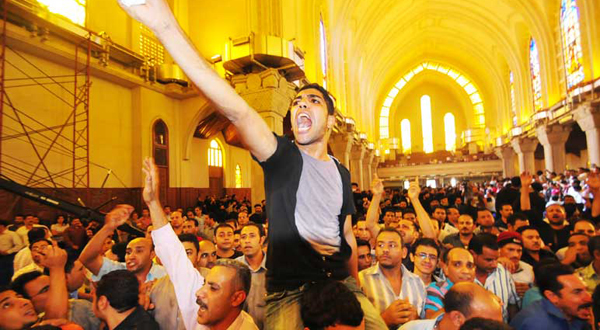

(Photo Presidency handout)

The “President’s project”

A simple comparison of the information provided for the project to the official declared targets makes it easy to identify certain features that suggest discrepancies, obscurantism and ultimately the construction of a social paradox.

The project was initiated in 2014 as part of President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi’s presidential programme, aiming to increase the agricultural land by 20% through reclamation of 1.5m acres (this figure was only that provided for in the first stage of the programme as it aimed to eventually reclaim 4m acres)in areas such as the Western Desert, Toshka and other areas outside the Delta, with the estimated costranging between EGP 150bn and EGP 200bn.

There are notable discrepancies in the numerous changes that followed the primary plan. At the beginning, the project’s scope was to address 1m acres. However, shortly thereafter, this figure fell to just 500,000 acres. As for the additional 1m acres, they are set to be divided equally over two subsequent stages of this first phase.

Similar changes were made concerning the deadlines, with a shift from mid-2015 to mid-2017.

“Yes, the original plan was changed on the orders of the president to see how the first phase will unfold,” said Eid Hawash, the media consultant at the Ministry of Agriculture, before adding that the first phase is expected to proceed in an “outstanding manner”, once it is launched.

The same seemingly arbitrary pattern persisted with the distribution of lands. Once information regarding the project was disseminated, it was announced that the youth demographic would be granted 50% of the lands, with the other half going to investors and interested companies. Nevertheless, following recent reductions, the youth demographic’s share was cut down to just 25% of the total size of the land to be reclaimed, a move confirmed by Hawash.

As for the declared targets, vagueness predominates. Establishing fully developed urban communities with their own industries and service centres, providing new work opportunities, “reducing the food gap”, and exportation have all been mentioned, but little else is provided in terms of clear targets. There is even a dilemma regarding the grains and seeds to be sown in the different areas of the project.

“We don’t know much about the project or what its target is,” said agricultural expert Hossam Reda.

Echoing the same opinion is Gamal Seyam, Professor of Agricultural Economics at Cairo University. “This project, so far, is characterised by chaos and is improvised to a large extent. There is no real transparency. Most of the information we have is more or less day-to-day and derived from the media.”

Whether haphazard or intentionally obfuscatory, the project is clouded in an opaque haze. Former minister of irrigation Nasr Allam is bemused by the state’s actions saying that “the targets are not clear”.

The modern Egyptian state has embarked on a number of large agricultural projects since 1952, beginning with the popular land reform under president Nasser and the land reclamation during the same period, the Salihiya under Anwar Al-Sadat, and the infamous Toshka project under Mubarak. However, according to Allam, these projects rarely met purported targets, and in some cases, the projects even collapsed.

The government, through its distended network of officials and cronies, has been keen to distance any historical resonance with these failures. “This project can’t be compared with previous projects, such as Toshka, which failed due to the absence of rigorous control and supervision, as well as other political objectives. It is not the case this time,” said Hawash.

Yet the comparisons nonetheless made their way to the discussion table, as the media debate seized upon the political mirroring. Problems, such as the huge cost, desertification and the decreasing provision of land provided to the youth demographic in addition to the high threshold they face inefficiency reclaiming arable land when compared to the investors’ share and capacity, have all been attributed to the inconsistency with respect to the original plan.

(Photo Presidency handout)

Water scarcity, absence of feasibility studies – and consent

According to the experts, Egypt is certain to face a water shortage in the upcoming decade. Consequently, groundwater has become the focus of attention, and was designated as the solution to the problem.

Yet, the government managed to incite backlash when it declared its intention to drill up to 5,000 groundwater wells to irrigate 85% of the project. Ironically, this process – which is already ongoing– aims at securing water for cultivating only “non-water consuming” crops and seeds on the project’s lands.

Even with confirmations from officials regarding the abundance of water, experts have expressed their disapproval and concerns regarding such a plan.

Mahmoud Emara, an agricultural expert who has been vocal about his opposition to the project, warned against the likely disasters accompanying its continuation. Speaking to local media, he said: “This project threatens the strategic reserves of groundwater that will secure Egypt’s future if the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam is built.”

A dispute ensued concerning the studies carried out to explore and confirm the amount of existing groundwater before deciding on whether it is convenient to move forward with the project or not.

“The Ministry of Irrigation confirmed that all the lands within the project have enough groundwater to go on with the project,” according to Hawash. Reda agreed that some Italian studies dating back to 1978 verify the existence of groundwater in some of the project’s areas, such as in Ownyat, and that these studies were presented to the government previously.

However, he highlighted that this is not the case with all other areas. Meanwhile, Allam stated that the level of groundwater in the Western Desert has been diminishing for years, making it inadequate for the cultivation of all the full area of the project.

Moreover, others have expressed further doubt. Sameh Saqr, head of groundwater sector in the Ministry of Irrigation, warned, in a workshop held by the ministry and the European Union in Alexandria last October, that once the lands are distributed, the investors will only seek their own interests and will drain the water reserves, while the government lacks the capabilities required to supervise their usage.

Clashing targets: Youth, food shortage and exportation

The official rhetoric of the state concentrated on the project’s importance in creating new job opportunities for the youth. But the terms and conditions offered largely contradict this proclaimed assertion.

To start, those among youth demographic who are allegedly eligible to apply are only those below the age of 40, not working in any governmental job, and who are capable of paying 25% of the value of the land up front. The cost per acre averages EGP 200,000, according to Minister of Irrigation and Water Resources Hossam El-Moghazy.

More recently, El-Moghazy stated that the cost per acre will vary depending on the cost of the infrastructure, in an attempt to justify the absence of a set purchasing price.

Under such harsh conditions, new job opportunities would be extremely limited, if not impossible for most of those seeking them. Those capable of meeting these prerequisites would be extremely rare in a country suffering from a 13% unemployment rate, according to the official figures.

Even with Al-Sisi’s calls for better financing terms from banks (with interest on loans at less than 6%), it remains debatable whether banks will respond to this, and if it would have a positive effect. Not to mention, despite the fact that infrastructure will be extended to the youth, the additional cost of equipment and materials is prohibitively expensive.

Reda stated that it is “ridiculous” to expect unemployed young men to pay such figures and to accept such “unfavourable” terms.

Moreover, some suggested that agriculture, as a field, is no longer a feasible profession among the youth. Speaking to a local newspaper last August, Allam mentioned that the decline in the crop prices and the problem of fertilisers and pesticides caused agriculture to lose “its attraction as a career” among the youth.

If officials’ statements are to be believed, a number of Arab companies, mainly from the Gulf, are interested in investing in the project. Yet, nothing was mentioned about a similar interest among the youth demographic, whom the project is allegedly targeting.

Furthermore, many of the experts questioned the project’s putative aim: to cut down on food imports and fill the food gap. The field crops needed to fulfil this task, such as wheat and barley, were onlysporadically mentioned by the government, in contrast to fruits, olives or aromatics, which feature more heavily in the plans.

While 7,500 acres of the 10,000 in the Al-Farafra Oasis will be sown with wheat and barley, nothing suggest that this pattern will be followed in other areas, especially as these crops take a relatively longer time to be cultivated and to generate profit.

It is highly doubtful that investors would be attracted to these, in comparison to others crops, such as fruits and vegetables which are more suited for exportation. Commenting on this, Reda confirmed that, according to the information available, food self-sufficiency cannot be a feasible goal of the project.

With the calling into question of the new employment opportunities, the comprehensive development and establishment of urban communities, and the closure of the food gap, the only remaining realistic target is exportation.

In fact, the complicated dynamics surrounding all these aims flow in favour of exportation, to the extent that it can be fairly assumed that exportation is indeed the real objective, irrespective of all other populist mottos that have been stamped onto the project.

Amid the state’s financial crisis, the deficiency in the balance of payments, and the continuous depreciation in the value of the Egyptian pound, the state is resorting to exportation as the solution. With the agriculture sector already providing almost $5bn in exports, the expected rise in the inflow of hard currency is seen as the remedy. Yet, this would not improve the situation on the ground, with the problem of imports, mainly food imports, persisting.

(Photo Presidency handout)

Who’s success?

Following the inauguration, more information and details started to pour in. Nevertheless, the main questions remain unanswered concerning the type of success to be expected from this project. More importantly, whom would such successes serve: the regime, the masses or the investors?

In general, the terms and conditions are well disposed to investors above all other possible stakeholders. Supported by the land distribution and preferences towards certain types of plants and seeds suited for exportation and not internal consumption, they have a clear edge. Politically, the state would benefit in terms of cinching stability through reviving a nationalist discourse andachieving a certain degree of “development”.

If offering the youth demographic job opportunities were a target, then less severe terms would have been offered or at least a larger percentage of land parcelling.

Moreover, if reducing the food gap was a priority, certain types of grains should have been imposed by the government.Of course, the terms and conditions stipulate that investors should cultivate “strategic” grains to cut the internal deficiency of food.

But again, in a country that strives to attract investors, as witnessed in the Sharm El-Sheikh Egypt Economic Development Conference, it is these investors who likely have the bargaining power.

Some media outlets reported investors’ demands for customs exemptions on all of the equipment to be imported for the project. Discussions of who would incur the cost of drilling wells and extending other infrastructure have been raised by a number of people, including Allam. The government must provide such facilitations to attract external investors.

The state has declared that the rest of the project will be self-financed from the revenues generated in this phase, which are received by “El Reef il Masry”, the company authorised to operate the project. As such, this would relieve the government of any additional burden. Nonetheless, this depends on the investors’ involvement.

Thereby, the project becomes totally dependent on the investors’ success, which is bound to profits. Accordingly, the only tangible measure of success is the amount of profit investors expect to make. Investors will create job opportunities, but on a limited scale.

Moreover, the problems within the Ministry of Agriculture cannot be overlooked in this regard. Recent cuts in its budget, affecting its research centres – including those responsible for this project – and the arrest of the former minister of agriculture, Salah Helal, on corruption allegations have negative implications.

Further, the discrepancies between the stated targets and the expected ones suggest a paradoxical approach by the part of the government, echoing the neo-liberal policies of the previous regime, albeit with a nationalist inflection this time around.

However, in this iteration, a failure for such nationalist mega projects to perform will majorly affect this discourse and undermine the regime’s legitimacy.