The scene of thousands of doctors gathering for a general assembly vote, spilling out of the over-capacity Doctors Syndicate’s headquarters, and onto the street was in no way a singular event.

On 15 March 2008, a dozen doctors, who were cordoned off by an almost equal number of security personnel, were protesting at the stairs of the Doctors Syndicate, demanding fair salaries and calling for a strike as a tool to reach that goal.

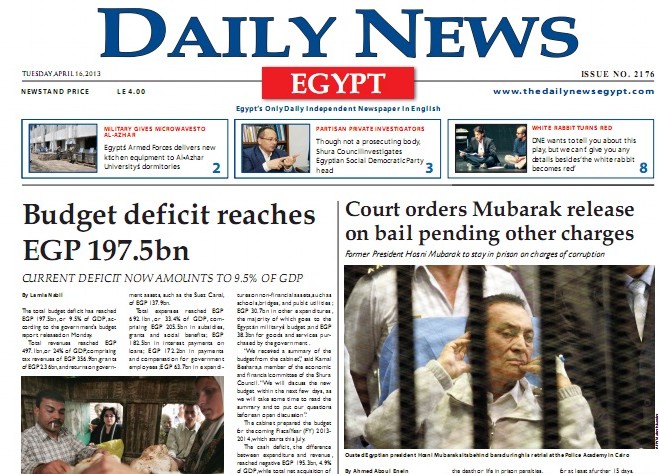

At the time, at the peak of Hosni Mubarak’s police state, more politicised protests were usually met with stringent security precaution that aimed to stifle any potential unrest.

The group of doctors standing at the steps in 2008 belonged to incipient movement called Doctors Without Rights. The movement was launched in May 2007 by Mona Mina in an environment of renewed political engagement evinced equally in other movements such as Engineers Against Curatorship, launched in 2003, and Keffaya, launched in 2005.

The founding statement of the movement focused almost entirely on ameliorating the doctors extremely poor financial appropriations allocated by the state. A starting salary for recently graduated doctors at that time was EGP 250 per month, while resident doctors at public universities were receiving EGP six per shift.

Almost nine years later, the situation has notably changed. According to what one of the movement’s founders stated, a recently graduated doctor now receives a starting salary of EGP 2000 and residents receive EGP 60 per shift.

However the increase in salaries, pensions, and allowances were not the biggest achievement for the group. The group’s founder, Mina, oversaw the change from a relatively powerless and left-leaning group of doctors in 2007 to what is now the group in control of one of the most important unions in Egypt.

How did they do it?

Rashwan Shaaban is one of the founding members of Doctors Without Rights and is currently a deputy secretary general of the syndicate. He believes that insistence on an inclusive policy made the difference for the group.

The scene in the syndicate in 2007 was a mixture of two controlling powers: the Muslim Brotherhood doctors and the state-backed syndicate head from the former National Democratic Party Hamdy Al-Sayed.

“At the beginning of it, there was cooperation between the movement, the syndicate board, and the brotherhood doctors. We were welcoming any cooperation for the good of the doctors,” Shaaban said.

The way the group operated was based on a principle that states union work is not political and it can include all parties, according to Shaaban. This inclusive cooperation came to an end in February 2008.

The group called for a strike to enforce a several increases in the financial appropriations for doctors and managed to gain the support of the syndicate’s general assembly, albeit difficulty. The syndicate board and the Brotherhood doctors did not like this alliance, according to Shaaban.

“A deal was struck between them and the government. El-Sayed and the controlling Brotherhood doctors dodged the general assembly’s decree and managed to thump down the strike by postponing it,” he said.

Since that moment, the political use of strikes has been used to form a unified front and make significant gains, being deployed in 2012 and 2014.

Inclusive or without principles?

In January 2014, the movement saw a sharp rift when six members, including those that were part of the group’s founding, were dismissed and five others were suspended over a dispute about the formation of the movement’s list that won in the syndicate’s election a month before.

The win that ended the 28-year dominance by Brotherhood doctors in syndicate seats did not signal a key victory for a core group of the movement. Rather they saw the movement’s attempts to parlay with private hospitals’ and administrative doctors to be a betrayal to the movement previous stances and its founding conception.

“In most of the meetings and conferences the movement took part in, its leaders were insistent that one of the most important reasons for the health system’s deterioration is that university professors of medicine are in charge,” recounted a former member of the syndicate’s board, Mohamed Fatouh, in an opinion column in 2015. He had attempted to outline an example of the paradoxes inherent to the growth of the movement and its political new allies.

However this alliance produced a syndicate board lead by Mina and the former dean of Cairo University’s faculty of medicine Hussein Khairy. The two managed to group together the largest gathering of doctors in Egypt’s history to take a stand against the state’s security policies and interventions in the health sector.

What’s ahead

“The medical insurance doctors and the young doctors are the most affected by the state policies towards the health sector and they were the ones who formed Doctors Without Rights,” said a young medical student, Mo’men Essam.

Essam is a member of his faculty’s student union at Assiut University and is a participant in the Doctors Syndicate’s activities. He remembers observing the rift in the movement and recalls that the alliance with university professors, disputes over the focus upon health conditions in prisons, and detained doctors were the main reasons behind the rift.

Despite the rift, Essam contends that the syndicate, controlled by the movement, is doing a good job in reaching out to change existing practices for medical students, who will become future doctors.

“The syndicate needs to reach out more to college students to pump new blood into the syndicate’s veins,” Essam said.

The syndicate should still train greater focus on problems in the health sector, according to Essam, since he believes that there should be a vision for repairing medical education.