Germany is one of the last countries to release the Oscar-winning Hungarian concentration camp drama “Son of Saul” in cinemas. It raises the never-ending question of whether fiction can truly do justice to the Holocaust.

“Son of Saul” limits itself to two perspectives – it’s nearly two hours of staring into a face, or over a shoulder. Either we peer into the countenance of Jewish concentration camp prisoner Saul Ausländer (Geza Röhrig) or we see how he – a man obsessed with one idea – rushes about the camp. In those moments, we look over his shoulder and take on his own range of vision.

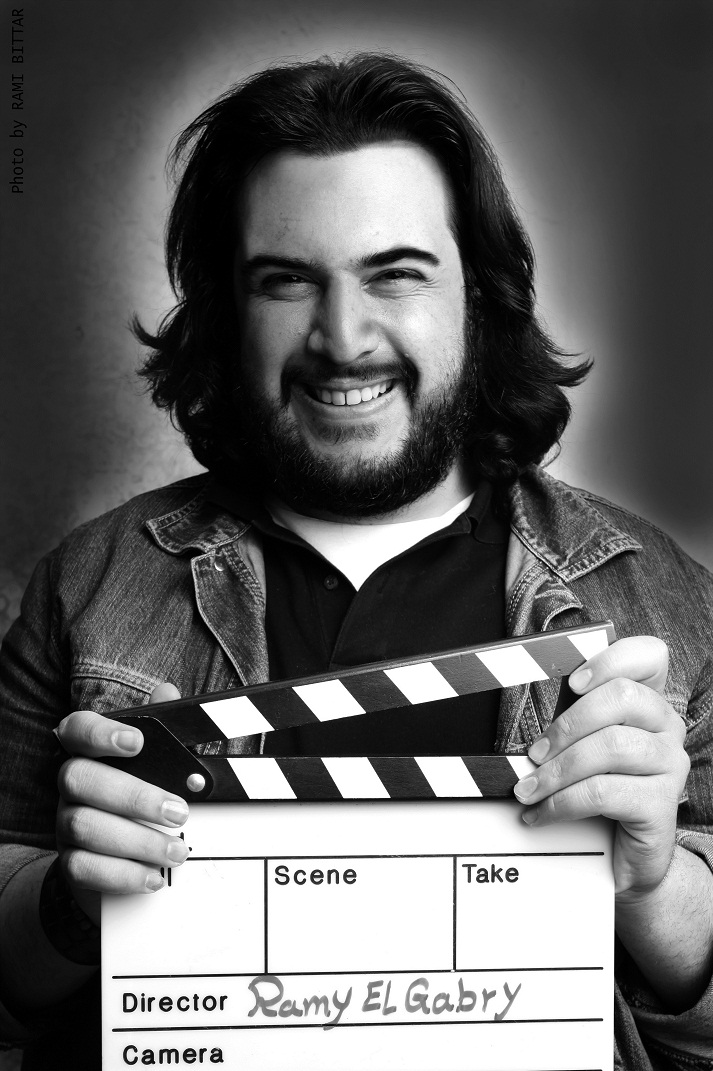

“Son of Saul,” by Hungarian director Laszlo Nemes, is in many ways a very unusual film. Its world premiere was celebrated last year at the Cannes Film Festival, where it won the Grand Jury Prize – the most important award after the Golden Palm. It then toured the film festival circuit before winning an Oscar in February for best foreign language film.

It’s been showing since late last year in cinemas in many countries around the world – but in Germany, the film had a difficult time finding a distributor. Only now – a week and a half after the Oscars – is the unusual Holocaust film opening in German theaters.

Rebellious mission

“Son of Saul” is set during the final months of World War II. In the concentration camps in Eastern Europe, camp commanders are preparing for defeat and retreat. It’s clear that the Red Army will be coming soon. In preparation, they quickly kill as many prisoners as possible, hectically and brutally.

Select prisoners are collected in so-called special commandos and tasked with the inhuman job of assisting in the murder of their fellow captives.

Saul Ausländer is a member of one of these lethal special commandos. One day, he sees a young boy who reminds him of his son. Not long after that, the boy is killed by a camp doctor.

Saul becomes obsessed with the burying the boy’s body and paying him his last respects.

Since the Jewish faith forbids cremation, Ausländer’s plan is also an act of rebellion.

Documentary-like feature with focus

In an oppressive way, Nemes shows how courageous but also absurd this scheme is. Unusually, the film is shown in a square format, which pulls the viewer even more into the picture and the happenings in the camp. Only the main protagonist and his direct surroundings are put in focus.

Everything else – even the crimes committed by the Nazis – seems blurry. The intense use of sound lends the film a great deal of authenticity, to the point that it practically has the effect of a documentary.

Nemes said he didn’t want to take the position of a concentration camp survivor, explaining his aesthetic approach. He didn’t intend to show everything that went on in the camp, he added. “I wanted to show the story as simply and archaically as possible.” That’s what differentiates “Son of Saul” from scores of other Holocaust films over the decades.

Nemes explained that he had already been frustrated by Holocaust films. “They often try to tell a story of survivor and heroism,” while at the same time romanticizing the past. “Son of Saul,” on the other hand, is characterized by sober simplicity, which makes it all the more impactful.

Is Holocaust fiction allowed?

After the premiere in Cannes, critics touched on a fundamental problem in the film. Is it legitimate for a fictional feature film to tackle the topic of concentration camps? Should brutal deeds, murders and gassing be portrayed by actors? The debate is not new – it has previously surfaced in literature, theater, art and philosophy.

The film critic for one of Germany’s major newspapers asked after the premiere, “Can anyone imagine the filming process? The relationship between the actors and the characters they are playing?” She reached the conclusion: “There are good reasons for the taboo that the Holocaust should not be the stuff of fiction. They should still be valid.”

Ultimately, viewers have to answer for themselves the question of whether the horrors of the Holocaust may be dealt with in fiction.

With “Son of Saul,” Nemes forged a path of his own. When Steven Spielberg released “Schindler’s List” in 1993, French director Claude Lanzmann responded with harsh criticism.

“The Holocaust is unique in that it is surrounded by a circle of flames, a boundary that may not be crossed because a certain absolute degree of atrocity is not transferrable,” wrote Lanzmann, condemning those who broke this codex.

However, the director only had praise for “Son of Saul,” calling it a kind of “anti-‘Schindler’s List'” – a film suited to keeping the memory of the genocide alive.