Protests scheduled for 25 April were not as massive as planned, taking place in limited areas, despite intensive political and civil calls for mobilisation. The state carefully directed its security bodies to double efforts in countering such demonstrations.

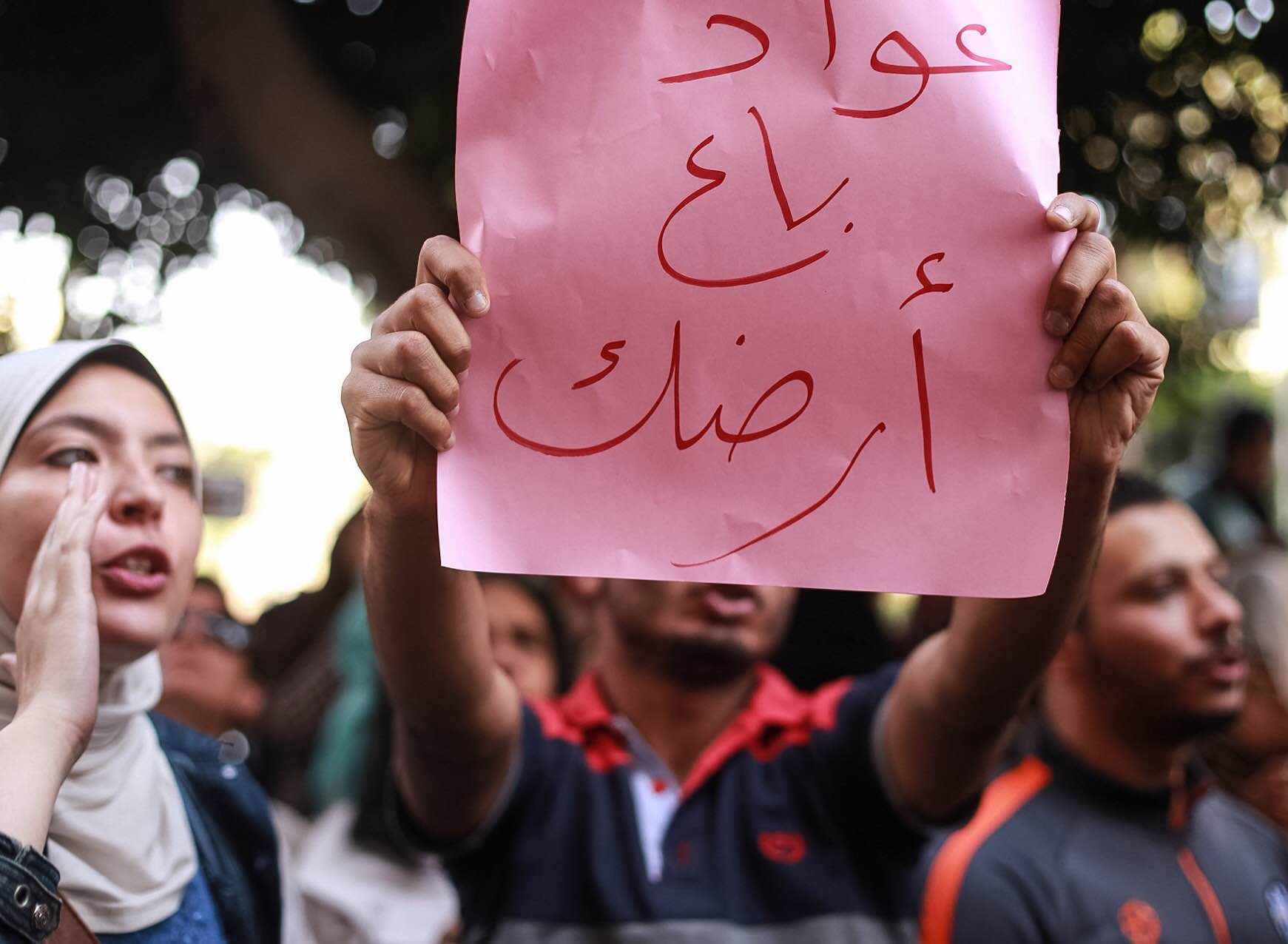

An unprecedented security crackdown prevented people from taking the streets to chant: “Tiran and Sanafir are Egyptian lands”. However, the protests that barely happened still hold a major significance in relation to the current political situation in Egypt.

The calls for protests came to highlight the political and social rejection of the maritime border demarcation agreement signed between President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi and King Salman bin Abdul Aziz Al-Saud, according to which sovereignty over the Red Sea islands of Tiran and Sanafir, long under Egyptian sovereignty, would be transferred to Saudi Arabia.

There are two events to look at. First, the wide-scale demonstrations which initially took place on Friday 15 April, along with its following incidents. Second, there were the calls for protests on 25 April, obstructed by an intensive security strategy, along with preceding incidents.

The 10 days in between reflect the core issue and present several aspects of the wider national cause.

The significance of the protests

Since the toppling of Islamist president Mohamed Morsi after the uprising of 30 June 2013, and the wave of pro-Muslim Brotherhood protests in 2013 and 2014, the public attention given to those protests gradually diminished, until the protests themselves almost disappeared.

However, not all forms of protesting vanished, simply because many of the people’s basic needs remain unmet, whether economic, social or political, let alone any of the demands for bread, freedom, dignity and social justice.

As such, hundreds of rallies and small scale demonstrations were organised in 2015 and continued through 2016 by different social and political factions. From young graduates demanding their right to jobs to retirees asking for their pension rights, workers for their labour rights, and people with special needs for their rights to integration in society and the work force—the list goes on.

This is in addition to journalists, who have on an almost weekly basis been defending freedom of the press, or human rights advocates decrying security violations against citizens, or even the families of thousands of detainees hoping for justice one day.

However, none of those demonstrations carried as much resonance as the Red Sea islands protests.

A “national celebration”

It is no coincidence that two national holidays on the 25th of two different months were selected by protesters to advocate for their demands.

When people took the streets back in 2011, they specifically chose 25 January for the significance of the day celebrated by the state: National Police Day. Police brutality and the increase of aggression against citizens—topped by the killing of Khaled Said at the time—were triggers to the January uprisings, which not only toppled former president Hosni Mubarak, but also his security bodies.

Likewise, the calls for protests against the maritime border agreement were scheduled for Sinai Liberation Day due to the implication of the cause: defending the sovereignty of Egypt over two Sinai islands which saw years of bloodshed when Egyptian soldiers fought in the war against Israel.

The link between the events and the selected days was, in itself, the message.

The 10 days in between

A severe security raid was the main characteristic of the period between 15 April and 25 April and is still ongoing.

Security forces detained over 100 citizens across the nation since Friday’s demonstrations, and further raids were conducted in the streets accompanied by arbitrary and random arrests, as well as house raids. The target groups were young political activists, human rights defenders, and also journalists and lawyers.

For the past five days, a chaotic scene unfolded as lawyers struggled to locate those arrested, in order to follow up on their legal statuses. Eventually, they obtained information on the charges facing the detainees, among which came an accusation in direct relation to Al-Sisi.

Sameh Samir, a rights lawyer working with the Egyptian Front to Defend Protesters, published a list of nine charges he obtained from prosecution authorities. The charges said the detainees took recourse to “violence to forcefully prevent the president of the republic from acting within his constitutional authorities”.

The charges commonly included crimes of “serving terrorist purposes” and “committing terrorist crimes”. Thereby, the detainees are accused of executing “terrorist plans” by using violence to overthrow the regime, change the constitution and its republican status, planning to attack police stations, obstructing law enforcement, and preventing authorities from performing their duties.

Moreover, charges include endangering social and public safety, disturbing public order, and promoting terrorist ideas through “online information networks”.

The ninth charge stated that the detainees “intentionally published false news, statements and rumours to damage the safety of the state and public”.

The “non-Brotherhoodisation” of the protests

The Muslim Brotherhood announced its participation in the protests called for by secular forces. However, their ‘request to participate’ was rejected.

The Socialist Popular Alliance Party (SPAP), one of the main advocates of the protests, refused their inclusion. The party stated that the Brotherhood’s “project” always aims at serving their “sectarian and illegitimate” motives.

The protests on 15 April, known as “Friday of the Land”, held at the Press Syndicate and other downtown areas, did not include Brotherhood members. Moreover, the Brotherhood did not take any action until one day before the Friday protests.

Meanwhile, during the week that followed the signing of the agreement, other major political opposition parties and figures not only expressed their rejection of the agreement, but also made efforts to raise debates and present information to the public to support their claims on the sovereignty of the islands. Conversely, the Brotherhood only issued a statement on 14 April, nearly a week after the signing.

The role of social media in the face of state restrictions

The debates on the islands and the calls for protests took place on social media networks. This came amid restrictions on the media, and direct restrictions imposed by Al-Sisi when he publicly announced “the end of the discussion”.

Yet, social media was stormed with published documents, research, and debates on the islands issue. It was also through social media that networks of information were formed to be able to follow up on the detention of protesters and others outside demonstrations.

The significance of the protests—even without taking place—was not only reflected in the significant numbers of security personnel deployed in the streets, but also in the establishment of online information portals to oppose protesters on social media.