Structural transformation is the main pillar through which economies can convert from being just preliminary economies to more complex economies by reallocating different economic sources, such as agriculture, services, or manufacturing, said Amirah El-Haddad, a professor of economics at Cairo University.

In research conducted by El-Haddad, she has linked the failure of the Egyptian economy to the slow growth rate of the manufacturing sector, which results from difficult industrial policies that more often than not provide the state with a lot of control through patronage, unfair competition, and incentives that are directed towards loyal groups. The failure also results from a lack of a clear vision to drive the industrial sector on the path of structural transformation, she added.

Egypt can achieve structural transformation by increasing production, diversifying the economy, increasing the technological component for Egyptian products, and increasing the added value to products for any locally manufactured products, Haddad said.

Patronage systems are made to guarantee the loyalty of main economic and political groups, she said, and the inner circles of power guarantee the continuity of such governments—such as the president and close acquaintances who often have high ranking positions in such countries.

(Photo Handout to DNE)

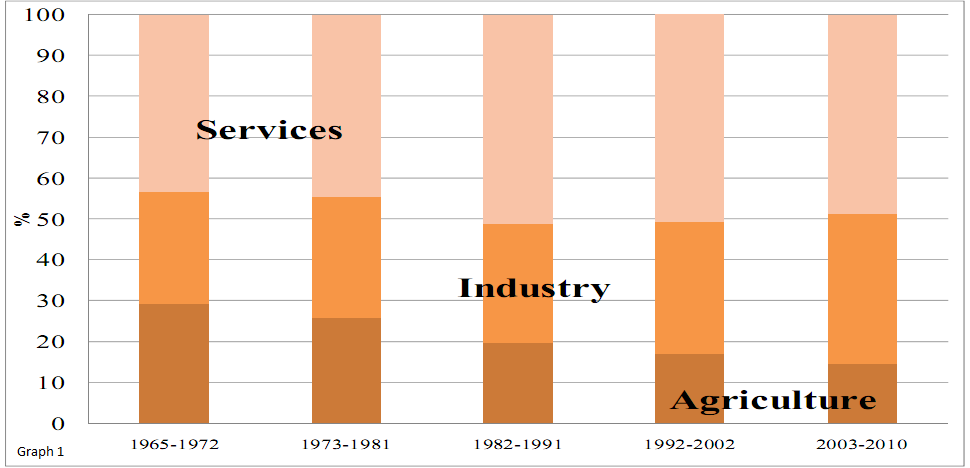

Haddad added that one of the elements that hinder Egypt’s structural transformation is a focus on non-manufacturing activities such as mining, construction, and general facilities. Graph 1 shows that Egypt has been expanding the services sector, yet shows slow growth rates in the manufacturing sector and negative growth in the agriculture sector.

Exports play a large role in a country’s ability to structurally transform through industrial policies. Grapg 5 shows a slight structural transformation in exports. Crude oil exports and natural gas decreased by 6%, and the manufacturing exports between 1980-2004 increased, which exceeded 11% between 1981-2002. Haddad said, however, with trade liberalisation and increased competition, this transformation was halted, and the 2008 financial crisis made it even worst.

With structural transformation being a reasonable solution, but a challenging one to implement, Haddad presented short-, medium-, and long-term industrial policy changes in her research.

Short-term industrial policies

When it comes to short-term industrial policies, externalities are an important factor that come into play and can both negatively and positively affect a party through costs or benefits incurred, Haddad said. Economists tend to urge governments to internalise these externalities so that the costs or benefits can be incurred only by those who chose to incur it, Haddad added.

In the research, Hadded shows that, coupled with market failure, externalities cause a loss to such economic activities. These externalities can also cause coordination failure between dealers in the market or even information/technology/knowledge spillovers.

The research said that in 2006 a strategy for industrial structural transformation in Egypt was made to overcome a lot of the consequences of externalities through nine sectors—human resources and entrepreneurship, availability of funding, infrastructure, innovation and technology, quality assurance, competitiveness, export, foreign direct investment (FDI), and local market production.

This strategy was to be implemented by three main parties: the Ministry of Industry and Trade, which is responsible for the medium and large companies, the Social Fund for Development, which is responsible for the small and micro companies, and the Ministry of Investment and the General Authority for Investment, the research added. The nine sectors were supported differently to achieve the desired goals through incentives, but their methods were flawed.

Haddad went on to explain why they were flawed and how to alleviate such problems. In order for these incentives to work perfectly and accommodate structural transformation for the short term, they must be accompanied by specific guidelines.

Firstly, according to the research, the incentives must be tied with performance indicators such as export rates, technological advancement rates, or even the rates of the added value of the product. These incentives must be clear, and have a simple and logical execution.

Secondly, these incentives must be designed dynamically and work seamlessly, Haddad added. For example, if the focus is on raising export rates, the export subsidy policy must be amended to encourage local production. To elaborate, if the focus is on the exportation of technologically advanced local products, then to activate the subsidy policy, the rates of needed exports must increase every year or the subsidy programme’s support will decrease each year or even be deactivated. Such dynamics can be applied on many sectors and for different purposes to achieve structural transformation, Haddad said.

Thirdly, a specific, committed timetable for incentives programmes and their end time must be announced, Haddad added. Fourthly, she continued, follow up and continuous evaluation must exist through independent inspectors to guarantee that the facilities have achieved the previously set limits for the subsidy programme.

Medium- to long-term industrial policies

There are four fields that act as tools for the economy that encompass producers, traders, employees, students, and all different segments of society. They enhance the efficiency of the economy, decrease cost, increase competition, and improve the economic atmosphere, Haddad said.

Governmental and institutional reform

The first field is governmental and institutional reform, which is important to let go of limitations and restrictions. Egypt ranks at the top of the list of countries with the most complicated laws, owing to the extreme bureaucracy and the lack of quality government services. This bureaucracy shows itself in the amount of time needed to register companies and in the fulfilment of “reporting requirements”, the research added.

In addition, the research mentioned that bureaucracy stands in the way of structural reform resulting from the government’s inability to adopt advanced management technologies such as information technology or to adopt enough reform plans to fix its manifesting bureaucracy.

Another important problem in this field is the human resources for the administrative organ of the state, for which the government produced a plan to fix this, but the parliament didn’t agree to it, Haddad said. It is important to improve the incentives system that state employees work under, Haddad said. This can be carried out through establishing a set of rules for reward and punishment on the basis of supervision, with the satisfaction of the citizen directing this system, she continued.

Automating and updating all government facilities to increase quality and production capacity could minimise chances of system exploitation and corruption, since automation makes them easier to supervise, Haddad added.

Another factor would be to substantiate the moral of “law above all else” in resolving trade disputes and ensuring contracts are followed fairly and thoroughly, Haddad said. Foreign direct investors must also not be exempt from taxes and customs to turn them into an unfair competition to local investors, but incentives must be offered to both sides equally.

Improvement of competitive atmosphere and the role of the military institution in the Egyptian economy

The second field is the improvement of a competitive atmosphere and the role of the military institution in the Egyptian economy. The state’s public establishments—and some private, but state affiliated—are currently protected by the Egyptian market and this needs to change, Haddad said.

For example, the cement, iron, aluminium, fertiliser, real estate, aviation, marine, railroad, and many other public sectors such as landline telecom, post services, and electricity, among others, are all controlled by the state, she added.

Haddad continued that the Egyptian telecom company owns 45% of the shares of Vodafone, and this ignores the Protection of Competition and Prohibition of Monopolistic Practices Law, so the state must stop interfering with private establishments, must be limited to an organisational role, and remain neutral to create a state of balance between the consumer, the producer, and the government.

The military institution is also an unfair competition to the private sector. The reasons are as follows: they use recruits in production although their job is to protect Egypt’s borders, Haddad elaborated, but not in being forced into labour with wages that are much lower than their private sector counterparts.

Furthermore, they don’t pay taxes on their profits, they don’t pay customs, and the army has the priority in getting imported raw materials before the private sector, which enables the army to set much lower selling prices for their products in comparison with the private sector, which in turn makes the army unfair competition, Haddad said.

Human and monetary infrastructure

The third field is human and monetary infrastructure. Increasing the production capacity is important, and this can only be achieved by reforming education and infrastructure to achieve this structural transformation.

A lot of Egypt’s educated youth are unemployed, and a lot of the sons of the working class are also unemployed due to high illiteracy rates. Haddad said this can only be changed through improving the overall quality of education, and allocating resources and effort towards creating quality education in primary, preparatory, and technical stages.

The monetary infrastructure is being dealt with through industrial zones and free trade zones on a limited scale. This problem needs to be addressed with a lot of fund resources, which is the investment in the human resources capital.

This can be achieved through abandoning the energy subsidy programmes, which weakly target low income families and deform the structural production economy, Haddad said. Also, abandoning the free university education, continuing the privatisation of state owned businesses, enabling the contribution of the private sector through public private partnerships, and utilising foreign and Arab grants efficiently can all work to contribute towards this goal, Haddad added.

Labour markets

The fourth and final field is the labour market, which is currently weak and is limited to targeting the sectors with the highest production rates, Haddad said. This has been happening for the past twenty years, she continued. Egypt also holds the last place from the 134 listed countries for work place quality.

Dynamics must enter the labour market through decreasing restrictive labour regulations, Haddad added. The flexibility of the labour market is also linked to housing and transportation infrastructure so they must also be improved, she said.