He was this year’s guest of honor at the Max Ophüls Prize Film Festival. The German director tells DW why his own film debut, 50 years ago, was initially a nightmare.His film “The Nasty Girl” was nominated for an Oscar in 1991 as the German entry for best foreign language film. His 1982 feature “The White Rose” focused on Sophie Scholl, one of the participants in the White Rose resistance movement against the Nazis.

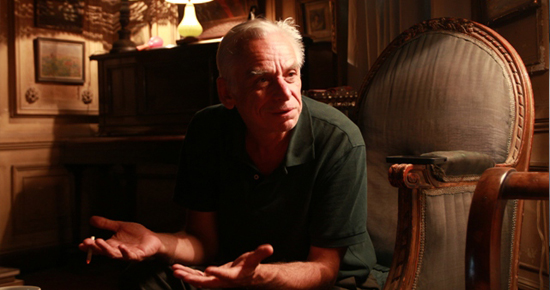

Michael Verhoeven has been married to actress Senta Berger for over half a century and has been directing films in Germany since the mid-1960s, as well as many TV productions. His feature debut, “The Dance of Death” (top picture), was released in 1967.

DW: You directed your first feature film 50 years ago. How was it at the time?

It was a big thing. My film was inspired by the August Strindberg play, “The Dance of Death” [Eds.: the English title of the movie] and in German it was called “Paarungen” (Pairings), a term borrowed from boxing. But it also referred to its biological meaning, to the struggle between married people – a dance of death, as Strindberg had described it.

I had recently married at the time. Everyone was asking me why I’d be doing such a story as a newlywed. But the film is about other things; it’s about psychology and how this fight is actually a kind of show. The characters are not enemies forever. That’s also the case in boxing. The fighters shake hands at the end of a match.

What do you remember from the premiere?

The premiere was really a memorable moment. It was in Cologne, in the theater Rex am Ring. All the actors were there, Lilli Palmer and Karl Michael Vogler, as well as my family. When we got there, we heard that the event was sold out, which was good news. But then no one showed up! Coming from Munich, I didn’t realize that in November people in Cologne celebrated Carnival. So no one came. It was deeply disappointing and painful.

What happened with the film afterwards?

We celebrated Carnival with the people afterwards. There was a big bar right by the cinema. It was full and people were dancing and singing. The evening combined two different atmospheres, our depressing film premiere and this great celebration in the dance clubs.

So the premiere had bad timing. We were very depressed at first. Everyone thought that this film was a big waste of time. That changed with the next premiere in Munich, in March 1968. There was a completely different atmosphere. We had great press and the film suddenly took off and was celebrated. We went to different festivals, and everything was great.

Nowadays, financing a project is always a big issue for first-time filmmakers. Was that the case for you at the time?

I can say this now because my wife is not here in the room listening… We took a mortgage on our house. And I’m not the only one – I know a few people who financed their first film that way. The great thing is that the film recouped all it costs – which wasn’t what we expected after the premiere.

There was a grant available for first films at the time, but the jury found my project too literary. They didn’t want to support it, saying it was disconnected from current society, so that’s why I didn’t get that funding.

What did you find interesting about the Strindberg play for your film?

Why was I fascinated by that play? Even though it is not staged very often, it is excellent because it explores the deep affection behind this struggle between men and women. I found it was a great play – and I still do.

What are your recommendations for young filmmakers today?

They should learn as much as possible about cinema, and that means they should watch films. They should ask: What’s different about that film compared to the last one they watched? What’s particular about the filmmaker’s signature? It can’t be identified at first; you have to have seen 100 films to recognize that each one is directed by someone in particular, and that the camera is done by someone in particular. And you can further analyze how they both work together by watching more films.

You also worked for television, even though you started out as a film director…

Cinema was way at the bottom when I started out in the mid-1960s. There weren’t many possibilities to finance a film that was not directly commercial. Some financing was based on weird tax models. I was advised by some to direct a film that no one would see, that would be screened 18 times and then disappear. The people who applied these tax models landed in jail; there actually were some films that “never existed.”

The interesting films at the time were mostly from abroad, such as those from the French Nouvelle Vague. My film, “The Dance of Death,” is set in 1900, but had a very modern approach, visually and through the acting. It was unusual though to have a film that wasn’t set in the present.

The film establishment fought against my generation of filmmakers, which included Alexander Kluge and all the others that were about 30 years old at the time. The establishment saw that we wanted to do something different, and they thought that would be the end for them. And they were right.

We were young and wanted to recreate the world. We had a good reason to want this: The Third Reich wasn’t even mentioned in history lessons when we were in school. That only came later.