As the Central Bank of Egypt (CBE) moves to fully remove any restrictions on foreign currency handling, the Egyptian pound seems to be under new pressures that could spark another downward spiral in the currency’s value.

In mid-June, the bank decided to move limits on international currency transfers, scrapping a $100,000 monthly limit on individual bank transactions in a long-awaited reform intended to lure back much needed foreign investment.

The bank will also remove restrictions on dollar deposits in the coming months, the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) mission chief for Egypt, Chris Jarvis, told the country’s Al-Borsa newspaper on Sunday.

“The central bank’s policy also includes removing remaining restrictions, including limits on dollar deposits, which we understand will take place in the coming months,” Jarvis added.

The changes include removing restrictions on using debit and credit cards in foreign currency.

The changes include removing restrictions on using debit and credit cards in foreign currency.

Egypt, which put in place strict controls on the movement of foreign currency after its 2011 political uprising, could face a currency dilemma in the few coming months for the above mentioned reasons, analysts told Daily news Egypt.

These moves formed a part of a package of economic reforms Egypt has to implement to bring back foreign investment, in return for a $12bn IMF loan.

As part of the three-year IMF deal, Egypt is also obliged to end those controls, which include a limit of $50,000 per month on deposits for importers of non-priority goods.

“I think that the Egyptian currency will be under pressure again, when the companies are going to transfer their profits. Another weigh on the local currency is that investors are overvaluing the dollar,” Jason Tuvey told Daily News Egypt.

“Look at the historical moves of the pound. You can feel the pressure is coming,” he added.

After keeping the pound way overvalued for more than five years, the bank in November announced it was “floating” the currency. It set a target price of 13 pounds to the dollar, far weaker than the previous official rate of 8.88. It also said it would let the pound move according to supply and demand.

Since then, the pound began sliding, more than expected and confounding the central bank. By 20 December, it hit 19.63, dangerously close to the barrier of 20 to the dollar. The CBE seemed, at this point, to have quietly started wrestling the pound back up.

The IMF also said it was surprised by how far the pound had weakened. “The exchange rate appreciated quite a bit, more than we expected,” Jarvis said in an 18 January press briefing.

The CBE took the IMF statement as a green light to strengthen the currency back up again in the belief that it had been unfairly weakened. By 22 February, it had strengthened the local currency against the dollar to 15.80.

Unfortunately, the market did not agree with that price and soon the black market, which had largely disappeared since flotation in November, began flourishing once more.

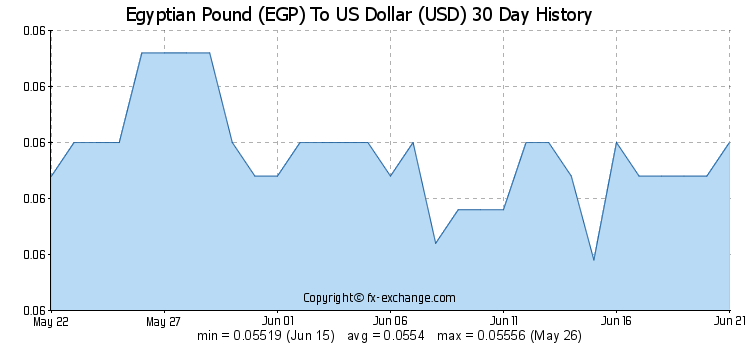

Since mid-March, the pound has been stuck at around 18.10 to the dollar, with almost no fluctuation.

“It could be the moment of truth of Egypt’s currency. Egypt’s money supply has been growing by about 20% per year, while GDP has hovered below 4%. That means the pound is losing approximately 16% of its value every year,” Focus Economy said in a research note.

The report added that “the risks to investors posed by a floating currency, in which currency value is largely determined by the market, comes from the potential for investors playing the market to lose their capital, should the currency swing dramatically. But, in the case of Egypt, the convergence of the currency’s official exchange rate and its black market rate should give investors the confidence that the worst of the fluctuations are over.

“Devaluing the pound was part of a broader package of reforms made by the Egyptian government in response to the country’s nearly depleted foreign currency reserves. States need a source of foreign reserves to engage in international trade, but emerging markets like Egypt are generally net importers and thus lack a stable source of foreign currency entering the country,” the note explained.

“For Egypt, two of its most important sources of dollars—tourism and foreign investment—dried up amid the violence and instability that plagued the country following the 25 January Revolution.”

According to the report without a steady supply of foreign currency entering the country, the CBE was forced to auction off scarce dollars to finance what the government deemed to be high-priority industries, such as wheat and medical equipment importers.

“Between 2011 and July 2016, Egypt used up $10bn of its foreign reserves, leaving only $50m. Businesses without access to dollars could not import needed inputs, forcing many to pay a premium on the black market or shut down altogether. Government budget deficits ran over 10%, among the highest in the Middle East, and public debt expanded to over 90% of GDP. Wealthy Arab neighbours, like Saudi Arabia, supported Cairo with cash infusions and subsidised oil in the years following the Arab Spring, but the drop in oil prices starting in 2014 caused fiscal problems in Gulf countries that forced them to pull back their support,” the report noted.

“Between 2011 and July 2016, Egypt used up $10bn of its foreign reserves, leaving only $50m. Businesses without access to dollars could not import needed inputs, forcing many to pay a premium on the black market or shut down altogether. Government budget deficits ran over 10%, among the highest in the Middle East, and public debt expanded to over 90% of GDP. Wealthy Arab neighbours, like Saudi Arabia, supported Cairo with cash infusions and subsidised oil in the years following the Arab Spring, but the drop in oil prices starting in 2014 caused fiscal problems in Gulf countries that forced them to pull back their support,” the report noted.

In 2015, the CBE imposed strict limits on dollar deposits to discourage demand on the dollar in the black market, and it also imposed 50,000 as a limit for maximum monthly depositing; however, a large part of these constraints were removed by March 2016.

The bank still keeps the maximum limit for individuals who work in importing products and non-basic goods at 10,000 daily, 50,000 monthly for depositing, and 30,000 for withdrawal.

“The central bank wouldn’t have taken such a step unless it was backed by a solid recovery in the foreign-currency situation,” said Hany Farahat, an economist at Cairo-based CI Capital Holding.

“It’s proof the currency crunch is dissipating, but challenges are still to come if companies decide to repatriate their profits,” Arafat added.

CBE Governor Tarek Amer said the removal of the restrictions will not affect foreign currency reserves.

“This comes as the central bank continues to take steps in the framework of economic reform, which it began to implement last year, and in order to strengthen confidence in the Egyptian economy,” a CBE statement said.

“The lifting of controls also contributes to attracting more foreign investment inflows and deposits from Egyptians abroad, given their ability to re-transfer them outside the country without any restrictions,” it said.

The CBE had already allowed commercial lenders to repatriate a part of dividends and have eased restrictions on the use of debit and credit cards abroad.

The government is trying hard to lure foreign investors in a way to build up its international reserves.

Egypt international reserves rose 9% in May from the previous month to $31.1bn, the highest level since February 2011.

Egypt’s economy has been struggling since the 25 January Revolution drove foreign investors and tourists away. The government is hoping a $12bn IMF loan signed last year will put it on the road to recovery, together with a rebound in investment.