Sleep-deprived people feel lonelier and less inclined to engage with others, avoiding close contact in much the same way as people with social anxiety, researchers at the University of California (UC), Berkeley, have discovered.

Worse still, that alienating vibe makes sleep-deprived individuals more socially unattractive to others. Moreover, well-rested people feel lonely after just a brief encounter with a sleep-deprived person, potentially triggering a viral contagion of social isolation.

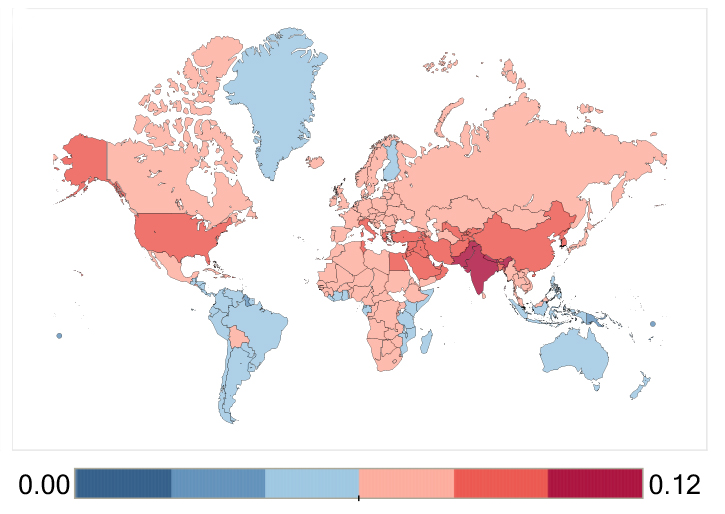

The findings, which will be published on August 14 in the journal Nature Communications, are the first to show a two-way relationship between sleep loss and becoming socially isolated, shedding new light on a global loneliness epidemic.

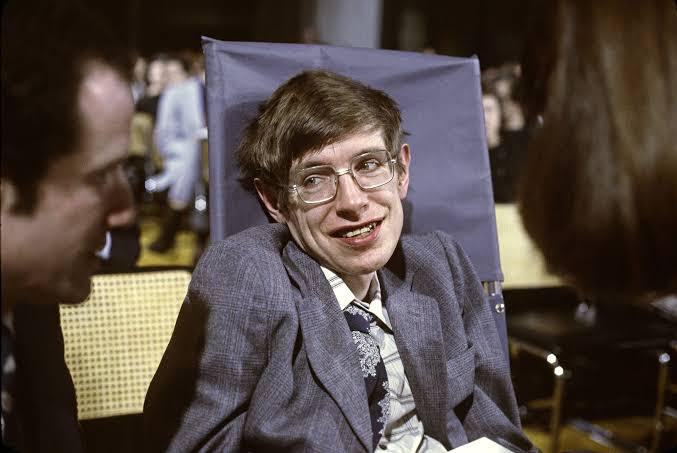

“We humans are a social species. Yet sleep deprivation can turn us into social lepers,” said study senior author Matthew Walker, a UC Berkeley professor of psychology and neuroscience.

Notably, researchers found that brain scans of sleep-deprived people as they viewed video clips of strangers walking toward them showed powerful social repulsion activity in neural networks that are typically activated when humans feel their personal space is being invaded, and seep loss also blunted activity in brain regions that normally encourage social engagement.

“The less sleep you get, the less you want to socially interact. In turn, other people perceive you as more socially repulsive, further increasing the grave social-isolation impact of sleep loss,” Walker added, elaborating, “that vicious cycle may be a significant contributing factor to the public health crisis that is loneliness.”

National surveys suggest that nearly half of Americans report feeling lonely or left out. Furthermore, loneliness has been found to increase one’s risk of mortality by more than 45%, double the mortality risk associated with obesity.

“It’s perhaps no coincidence that the past few decades have seen a marked increase in loneliness and an equally dramatic decrease in sleep duration,” said study lead author Eti Ben Simon, a postdoctoral fellow in Walker’s Centre for Human Sleep Science at UC Berkeley, adding “without sufficient sleep we become a social turn-off, and loneliness soon kicks in.”

From an evolutionary standpoint, the study challenges the assumption that humans are programmed to nurture socially vulnerable members of their tribe for the survival of the species. Walker, author of the bestseller, Why We Sleep, has a theory for why that protective instinct may be lacking in the case of sleep deprivation. “There’s no biological or social safety net for sleep deprivation as there is for, say, starvation. That’s why our physical and mental health implode so quickly even after the loss of just one or two hours of sleep,” Walker said.

How they conducted study

To gauge the social effects of poor sleep, Walker and Ben Simon conducted a series of intricate experiments using such tools as Functional Magnetic Resonance brain Imaging, standardized loneliness measures, videotaped simulations and surveys via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk online marketplace.

First, researchers tested the social and neural responses of 18 healthy young adults following a normal night’s sleep and a sleepless night. The participants viewed video clips of individuals with neutral expressions walking toward them. When the person on the video got too close, they pushed a button to stop the video, which recorded how close they allowed the person to get.

As predicted, sleep-deprived participants kept the approaching person at a significantly greater distance away—between 18 and 60% further back—than when they had been well-rested. Participants also had their brains scanned as they watched the videos of individuals approaching them.

In sleep-deprived brains, researchers found heightened activity in a neural circuit known as the ‘near space network,’ which is activated when the brain perceives potential incoming human threats.

In contrast, another circuit of the brain that encourages social interaction, called the ‘theory of mind’ network, was shut down by sleep deprivation, worsening the problem. For the online section of the study, over 1,000 observers recruited via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk marketplace viewed videotapes of study participants discussing commonplace opinions and activities.

The observers were unaware that the subjects had been deprived of sleep and rated each of them based on how lonely they appeared, and whether they would want to interact socially with them. Time and again, they rated study participants in the sleep-deprived state as lonelier and less socially desirable.

To test whether sleep-loss-induced alienation is contagious, researchers asked observers to rate their own levels of loneliness after watching videos of study participants. They were surprised to find that otherwise healthy observers felt alienated after viewing just a 60-second clip of a lonely person.

Finally, researchers looked at whether just one night of good or bad sleep could influence one’s sense of loneliness the next day. Each person’s state of loneliness was tracked via a standardised survey that asked such questions as, “How often do you feel isolated from others” and, “Do you feel you don’t have anyone to talk to?”

Notably, researchers found that the amount of sleep a person got from one night to the next accurately predicted how lonely and unsociable they would feel from one day to the next.

“This all bodes well if you sleep the necessary seven to nine hours a night, but not so well if you continue to short-change your sleep,” Walker said, elaborating, “on a positive note, just one night of a good night’s sleep makes you feel more outgoing and socially confident, and furthermore, will make you attractive to others.”