The World Bank (WB) issued the World Development Report (WDR) 2019 on Wednesday called “The Changing Nature of Work,” which studies how the nature of work is changing as a result of advances in technology today. Fears that robots will take away jobs from people have dominated the discussion over the future of work, but the WDR 2019 finds that on balance this appears to be unfounded.

Work is constantly reshaped by technological progress. Firms adopt new ways of production, markets expand, and societies evolve.

Overall, technology brings opportunity, paving the way to create new jobs, increase productivity, and deliver effective public services.

The report analyses these changes and considers how governments can best respond.

Daily News Egypt presents the most important findings, classifies them into points, revealing what each chapter of the study includes.

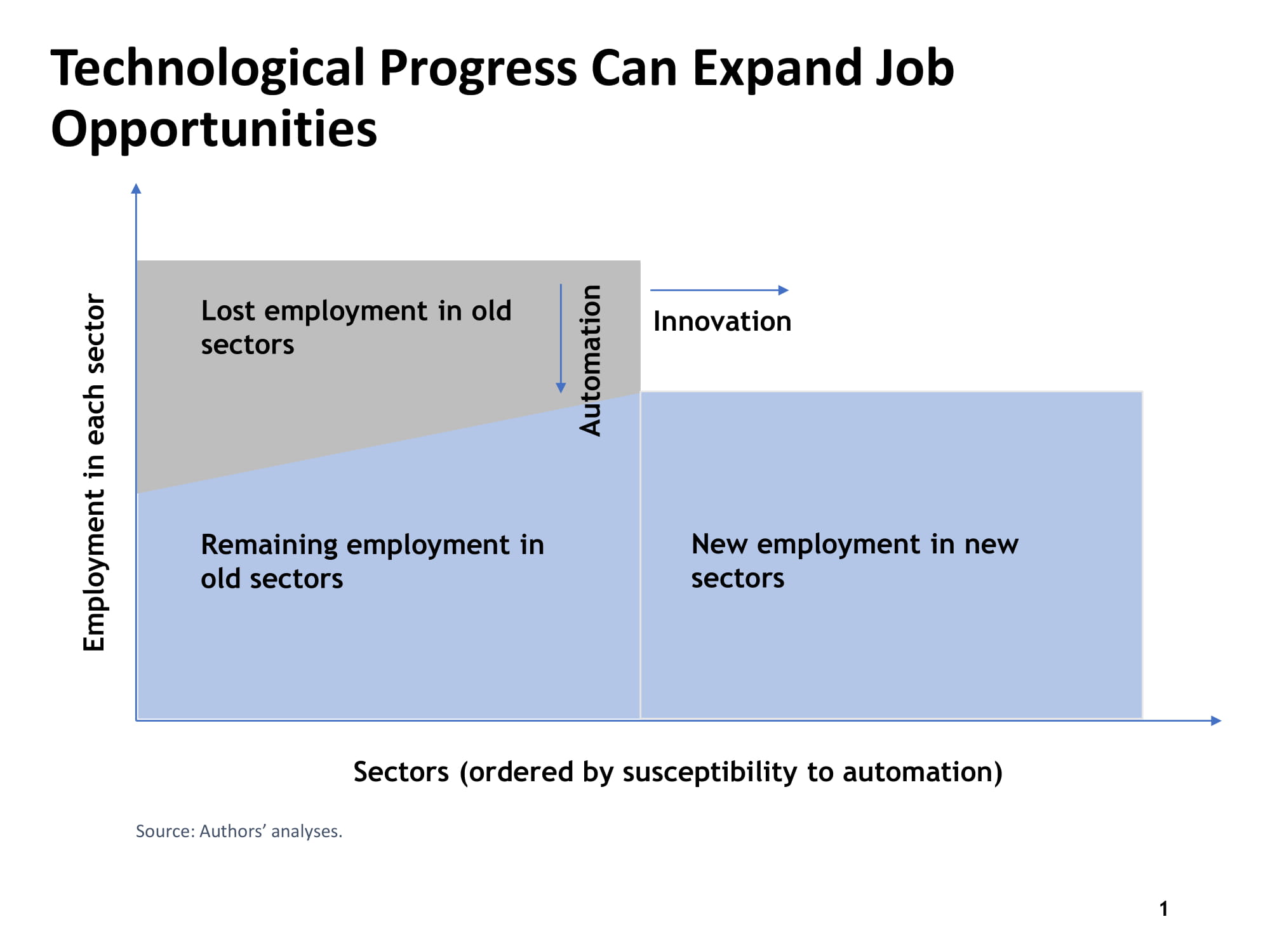

The first chapter of this study looks at the impact of technology on jobs, disclosing that in some sectors, robots are replacing workers. In other sectors, robots are enhancing worker productivity. And in further sectors, technology is creating jobs as it shapes the demand for new goods and services.

According to the report, these disparate effects of technology render the economic predictions of technology-induced job losses basically useless. Predictions sensationalise the impact of technology and stir fears, especially among middle-skill workers in routine jobs.

The report disclosed that technology does, however, change the demand for skills, noting that since 2001, the share of employment in occupations heavy in nonroutine cognitive and socio-behavioural skills has increased from 19% to 23% in emerging economies, and from 33% to 41% in advanced economies.

It continued that the payoffs to these skills, as well as the combinations of different skill types, are also increasing in those economies, but the pace of innovation will determine whether new sectors or tasks emerge to counterbalance the decline of old sectors and routine jobs as technology costs decline.

Meanwhile, whether the cost of labour remains low in emerging economies in relation to capital will determine whether firms choose to automate production or move elsewhere.

It mentioned that one feature of the current wave of technological progress is that it has made the boundaries of firms more permeable and has accelerated the emergence of superstar firms. Such firms have a beneficial effect on the demand for labour by boosting production and employment.

Furthermore, it noted that these firms are also large integrators of young, innovative firms, often benefiting small businesses by connecting them with larger markets. But large firms, particularly firms in the digital economy, also pose risks.

“Regulations often fail to address the challenges created by new types of businesses in the digital economy. Antitrust frameworks also have to adjust to the impact of network effects on competition. Tax systems in many ways no longer fit their purposes as well,” it added.

How does technological change affect the firm’s nature?

The report revealed that firms can rapidly grow thanks to digital transformation, which blurs their boundaries and challenges traditional production patterns.

Meanwhile, it brought out that the rise of the digital platform firm means that technological effects reach more people faster than ever before.

“Technology is changing the skills that employers seek. Workers need to be good at complex problem-solving, teamwork, and adaptability,” the report stated.

The report noticed that technology is changing how people work and the terms on which they work. Even in advanced economies, short-term work, often found through online platforms, is posing similar challenges to those faced by the world’s informal workers.

According to the report, at the economywide level, human capital is positively correlated with the overall level of adoption of advanced technologies. Firms with a higher share of educated workers do better at innovating. Individuals with stronger human capital reap higher economic returns from new technologies.

According to the report, at the economywide level, human capital is positively correlated with the overall level of adoption of advanced technologies. Firms with a higher share of educated workers do better at innovating. Individuals with stronger human capital reap higher economic returns from new technologies.

“By contrast, when technological disruptions are met with inadequate human capital, the existing social order may be undermined,” according to the report.

In chapter three, the report addresses the link between human capital accumulation and the future of work, looking more closely at why governments need to invest in human capital, and why they often fail to do so.

The report asserted that investing in human capital is a priority to make the most of this evolving economic opportunity.

It mentioned that there are three types of skills which are increasingly important in labour markets including, advanced cognitive skills such as complex problem-solving, socio-behavioural skills such as teamwork, and skill combinations that are predictive of adaptability such as reasoning and self-efficacy.

The report disclosed that building these skills requires strong human capital foundations and lifelong learning.

“The foundations of human capital, created in early childhood, have thus become more important. Yet governments in developing countries do not give priority to early childhood development, and the human capital outcomes of basic schooling are suboptimal,” according to the report.

WB’s new human capital project

The third chapter of the report introduces the WB’s new human capital project, to ensure effective policy design and delivery, more information, and better measurement of foundational human capital are needed, even when there is full willingness to invest in human capital.

The project has three components: a global benchmark—the human capital index, a programme of measurement and research to inform policy action, and a programme of support for country strategies to accelerate investment in human capital.

The index is measured in terms of the amount of human capital that a child born in 2018 can expect to attain by the end of secondary school, considering the risks of poor health and poor education that prevail in the country in which the child was born during that same year. In other words, it measures the productivity of the next generation of workers relative to a benchmark of complete education and full health.

Part of the ongoing skills re-adjustment is happening outside of compulsory education and formal jobs. But where?

Chapter four answers this question by exploring three domains—early childhood, tertiary education, and adult learning outside jobs—where people acquire specific skills that the changing nature of work requires.

According to the report, investments in early childhood, including in nutrition, health, protection, and education, lay strong foundations for the future acquisition of higher order cognitive and socio-behavioural skills. From the prenatal period to age five, the brain’s ability to learn from experience is at its highest.

“Individuals who acquire such skills in early childhood are more resilient to uncertainty later in life. Tertiary education is another opportunity for individuals to acquire the higher-order general cognitive skills—such as complex problem-solving, critical thinking, and advanced communication—that are so important to the changing nature of work but cannot be acquired through schooling alone,” the report stated.

“As for the current stock of workers, especially those who cannot go back to school or to university, reskilling and upskilling those who are not in school or in formal jobs must be part of the response to technology-induced labour market disruption. But only rarely do adult learning programmes get it right. Adults face various binding constraints that limit the effectiveness of traditional approaches to learning. Better diagnosis and evaluation of adult learning programmes, along with better design and better delivery of those programmes, are needed,” the report added.

Chapter four of the report explores these issues in greater detail. Work is the next venue for human capital accumulation after school.

How successful have economies been in generating human capital at work?

How successful have economies been in generating human capital at work?

Chapter five of the report answered this question by stating that advanced economies have higher returns to work than emerging economies.

It explained that a worker in an emerging economy is more likely than a worker in an advanced economy to find themselves in a manual occupation which is composed largely of physical tasks.

“An additional year of work in cognitive professions increases wages by 3%, whereas for manual occupations the figure is 2%. Work provides a venue for a prolonged acquisition of skills after school—but such opportunities are relatively rare in emerging economies,” it found out.

What can governments do?

The report suggests areas in which governments could act, which includes investing in human capital– particularly early childhood education–to develop high-order cognitive and socio-behavioural skills in addition to foundational skills.

In addition, enhancing social protection, a solid guaranteed social minimum, and strengthened social insurance, complemented by reforms in labour market rules in some emerging economies, would achieve this goal.

The report also suggests creating fiscal space for public financing of human capital development and social protection.

It mentioned that property taxes in large cities, excise taxes on sugar or tobacco, and carbon taxes are among the ways to increase a government’s revenue. Another way is to eliminate the tax avoidance techniques that many firms use to increase their profits. Governments can optimise their taxation policy and improve tax administration to increase revenue without resorting to tax rate increases.

“Governments can raise the returns to work by creating formal jobs for the poor. They can do this by nurturing an enabling environment for business, investing in entrepreneurship training for adults, and increasing access to technology,” the report suggests.

“The payoff to women’s participation in the workforce is significantly lower than for men—in other words, women acquire significantly less human capital than men do from work. To bridge that gap, governments could seek to remove limitations on the type or nature of work available to women and eliminate rules that would limit women’s property rights,” the report stated.

The report uncovered that workers in rural areas face similar challenges when it comes to accumulating human capital after school, noting that there is some scope for improving the returns to work by reallocating labour from villages to cities. However, in rural areas technology can be harnessed to increase payoffs to work by increasing agricultural productivity.

Uncertain labour markets call for strengthening social protection. This topic is explored in chapter six.

The report discovered that traditional provisions of social protection based on steady wage employment, clear definitions of employers and employees, and a fixed point of retirement are becoming increasingly obsolete.

It noted that in developing countries, where informality is the norm, this model has been largely aspirational.

The report also brought out that spending on social assistance should be complemented with insurance that does not fully depend on having formal wage employment.

“As people become better protected through enhanced social assistance and insurance, labour regulation could, where appropriate, be rebalanced to facilitate work transitions,” the report assured.

Changes in the nature of work, compounded by rising aspirations, make it essential to increase social inclusion. To do so, a social contract should have at its centre equality of opportunity.

Potential elements of a social contract

Chapter seven considers potential elements of a social contract, which include investing early in human capital, taxing firms, expanding social protection, and increasing productive opportunities for youth.

The report pointed out that in order to achieve social inclusion, some emerging economy governments will have to devise ways to increase revenue. Therefore, in chapter seven the report describes how governments can create fiscal space through a mix of additional revenues from existing and new funding sources.

It stated that the potential sources of revenue are imposing value added taxes; excise taxes; carbon taxes; charging platform companies taxes equal to what other companies are paying, and revisiting energy subsidies.