Negotiations between Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) are still ongoing over its filling and operation. The Egyptians have been closely following the updates since both President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi and Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry repeatedly stressed the issue is a matter of life and death.

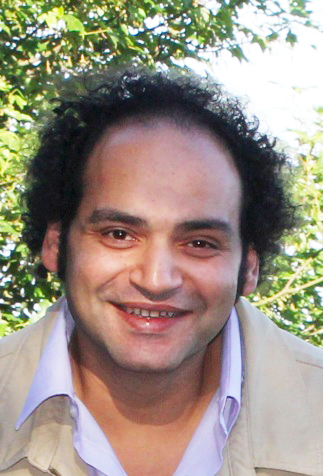

Daily News Egypt met with Peter Hany Riad, assistant professor at the Irrigation and Hydraulics Department, Faculty of Engineering at Ain Shams University, to clarify some unclear points regarding the different scenarios of filling the GERD reservoir.

Can you give us a brief summary about the GERD?

Can you give us a brief summary about the GERD?

The GERD is a gravity dam on the Blue Nile River in Ethiopia. It has been under construction since 2011. It is in the Benishangul-Gumuz Region of Ethiopia, about 15 km east the country’s border with Sudan. Its reservoir capacity is 74bn cubic metre (cm), of which 14.8bn cm is dead storage and 59.2bn cm is active storage.

The dam’s turbines are installed at a certain level to avoid the entrance of sediments inside the turbines. Below this level, water and sediments are entrapped which is the dead storage of the reservoir, while above this level is the active storage.

Its main purpose is generating electricity power at 16,153GW per year, in that case it will be the largest hydroelectric power plant in Africa as well as the seventh largest in the world.

What are the potential impacts of GERD on Egypt?

Many experts and studies are expecting significant impacts on Egypt, mainly during the filling stage of the GERD’s reservoir. This can be worse in years with average or low inflow from the Blue Nile. If no cooperation has occurred in the filling stage between the three countries, it is expected that a gradual decrease in Lake Nasser, High Aswan Dam’s reservoir, volume occurs and accordingly a shortage in power generation.

Most of the population in Egypt (more than 100 million in 2019) relies heavily on the Nile River which is the main source of the water supply. The Nile represents more than 85% of the conventional water resources in Egypt, mostly consumed in irrigation. Rainfall in Egypt is scarce as it is estimated at 1.5bn cm per year, while rainfall in Ethiopia is around 820bn cm per year and in Sudan around 1.93trn cm per year.

Egypt is reusing agricultural drainage and treated waste water four to seven times per year to cover its needs. In Egypt, there are approximately 8.5m feddan allocated to agriculture, each feddan needs in average 5bn cm of water per year.

What are the GERD’s impacts on Sudan?

For Sudan, positive and negative impacts are expected. The main positive impacts are buying electricity from the power generated by the GERD, and accumulating large amounts of sediments upstream the dam, which in turn will extend the Sudanese dams. In addition, the flow coming out of the GERD will be uniform along the entire year, instead of being concentrated within three to four months per year, which used to cause many problems like inundation of the river banks or flooding villages.

However, it will also cause severe reduction in the natural fertilizers that used to be carried out by the river to Sudan. In case of the dam’s failure, it will threaten the lives of thousands in Sudan. Moreover, the ecosystem in areas that the Nile River used to pass through will be affected as the water flow will be lower and controlled, and the groundwater table will be reduced.

What are the potential scenarios for filling the GERD?

Recently, I made a practical research study about the different scenarios for filling the GERD and their impacts on both countries, Egypt and Ethiopia. For this purpose, I have built up a model on excel using a long period of water inflow with historical data.

In the first scenario, filling on predetermined number of years, five or seven years, which means equal cuts every year. In case of five years, the filling volume will be 74bn cm in five years which means 14.88bn cm per year. In case of the seven-year scenario, the filling volume in five years will be 74bn cm which means 10.63bn cm per year.

In the second scenario which I support, the filling volume will be based on a percentage of the incoming flow in different cases either dry or wet seasons with different percentages.

Based on some historical data, some assumptions were considered. Egypt consumes at least 74bn cm annually from Lake Nasser, where evaporation losses annually amount to about 14% of the lake volume. The minimum critical level is 160 cm, but below this level there will be significant losses in hydropower generated by the High Aswan Dam and the agricultural lands might be lost and devastated.

What did your research conclude?

The main conclusions were that scenario one has a high risk to Egypt, especially in cases of frequent average or low incoming flow. It can also be impractical to Ethiopia especially in cases of frequent high incoming flow.

The second scenario showed more flexibility for both countries; less risk to Egypt and more practical to Ethiopia. In cases of high inflow (above the average), maximum cutting percentage should be 30%. In cases of low inflow (below the average), maximum cutting percentage should be 20% or less (depending on the degree of the inflow). It is recommended to start filling, while Lake Nasser has a high level above 165m cm.

The number of years should not be determined in advance, as this depends mainly on degrees of the incoming flow annually. If the filling years has high flows, then the GERD reservoir will be filled faster and vice versa.

Why have you chosen the Aswan High Dam as a reference in your study? How similar is it to GERD?

The High Dam in southern Egypt impounds the largest man-made reservoir on the Nile River, Lake Nasser, with active capacity of 132bn cm. It is a multipurpose dam for flooding control, providing water storage for irrigation, and generating hydroelectricity.

It is the safe valve against high floods and long-term storage against droughts. It protected Egypt from famine due to severe drought in the period from 1978 to 1987. It is expected that the High Dam and its reservoir will be the most influenced dam and impounded reservoir by the GERD, that is why my study was concentrated on the High Dam.

What are your recommendations to overcome such challenges?

Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia are three great countries with common long history and civilisation. I believe that they can create from their challenges new opportunities for exchanging benefits and cooperation. Nile River used to be a strong bond not a conflict.

The three countries should work together on realising the maximum development for each without harm to the others. There should be an insurance for countries which might be harmed, paid by the countries which get benefits or offer compensations. In cases of lost lands or changing crop yields, the other countries can offer new lands or offer percentage out of their profits to import the lost crops.

It is highly important for the new dam to have an integrated management team consisting of many experts from the three countries. Models and researches should cover the impacts of the new dam to guarantee the best operation and control.

Many projects can be carried out or completed in upper basin countries to save so much water in new constructed canals like in Mashar basin, Bahr El Ghazal, and Jonglei.